How beer led to one of Alabama’s biggest bipartisan wins in a decade

It’s been 10 years. And the change in downtowns across Alabama is noticeable, if not outright remarkable.

“The entertainment district is the artery of the city,” said David Clark, president & CEO of Visit Mobile. “Every city needs a heartbeat of the downtown and that is what the entertainment district does.”

In 2015, Alabama state lawmakers blocked Birmingham from raising its minimum wage. They thwarted Montgomery’s efforts to increase its occupational tax in 2020. They even enacted a controversial law prohibiting cities from removing Confederate monuments, forcing cities to hide them with plywood and haul them away in the dead of night.

For Alabama cities, the Legislature’s preemption powers have long loomed large.

But the relaxation of alcohol rules and the creation of “entertainment districts” one decade ago is now touted as among the most successful moves state lawmakers have made to help cities, reawakening downtowns from Mobile to Birmingham to Huntsville to Montgomery.

Inspired by the free-flowing vibe of New Orleans, the notion of leisurely drinking beer and wine outdoors in Alabama would have been almost unthinkable a generation ago in the heart of the Bible Belt.

But in 2012, the state even allowed for outdoor drinking on Sundays.

“The implementation of these districts has encouraged retail and restaurant growth, increased tourism and downtown engagement,” said Greg Cochran, executive director of the Alabama League of Municipalities, “thus allowing for increased economic investment, creation of sustainable jobs and enhanced quality of life for their communities.

‘Catalyst’ and expansion

Revelers attending a Mardi Gras style parade in downtown Mobile, Ala., on Friday, May 21, 2021, eat outside of Loda Bier Garten ahead of the parade within the heart of one of the city’s entertainment districts. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Created in 2012, the legislation allows cities to create, define, and regulate their own entertainment districts. In short, the law allows for outdoor consumption of alcoholic beverages within a defined area as long as the drinks stay in plastic cups.

Even violence that can sometimes happen within or near a district is not holding them back. In Mobile, a proposal to roll back the hours within the entertainment district following a deadly New Year’s Eve shooting was defeated by the bar and restaurant owners.

Related content:

If anything, state lawmakers are expanding the districts and keeping a hands-off approach toward regulating them. In fact, local control is so thorough, the state does not track nor compile a list of cities that have one.

The original state law capped Birmingham’s districts at five, while other cities were capped at two. But the law has since expanded, allowing cities like Huntsville to add up to five districts.

Birmingham, the state’s only Class 1 municipality, is now allowed to have up to 15 districts under legislation approved last year.

The law also led to loosening of other restrictions within the past 10 years. A ban on sidewalk beer and wine consumption in Mobile was eliminated in 2017. Craft breweries, in recent years have been allowed to have their products OK’d for outdoor consumption within the districts.

“From the perspective of what the State Legislature has passed in recent history that has helped Birmingham the most, this is probably it,” said Jonathan Austin, a Birmingham attorney who served on the City Council from 2008-2017 and led the city’s efforts in lobbying lawmakers for the law.

“Often you see Birmingham at odds with the Legislature,” Austin said. “It’s a conservative legislature and Birmingham is a left-leaning city. Obviously there will be challenges and disagreements. But this one particular issue is something we all agree on it.”

Massive impact

No economic impact study on the state’s entertainment districts exists, though the state’s tourism director says they are a big part of the state’s tourism growth.

“Without this support,” Lee Sentell, the state’s tourism director, said, “we could not have doubled tourist spending in just 10 years to more than $23 billion.”

Entertainment districts are often associated with some of the largest city development projects in recent years.

In Birmingham, for instance, the Uptown entertainment district that was created in 2015, was expanded last year to include Protective Stadium and the newly constructed City Walk underneath I-20/59. The city has three other entertainment districts – Pepper Place and Five Points, approved in 2010; Avondale granted in 2020.

The Camp at MidCity in Huntsville, Ala., as pictured in 2017. (file photo)

Huntsville has the most with five districts within and near its downtown area. Quigley that connects with Meridian Street and encompasses the heart of the city’s downtown, became the city’s first and served as a pilot for the future entertainment districts. Since then, Huntsville has added the Village of Providence, S. R. Butler Green at Campus 805, Mid City that includes numerous businesses including Top Golf and the Orion Amphitheater, and Bridge Street Town Centre.

“They have been the catalyst for economic development and have been welcomed by businesses, residents and visitors alike,” said Kelly Schrimsher, spokeswoman for the city of Huntsville, which eclipsed Birmingham within the past decade as the state’s largest city.

The Wharf in Orange Beach is fully open and offering some new attractions for summer 2020.

Montgomery’s entertainment district was the first to be approved in Alabama, followed by The Wharf in Orange Beach.

But 10 years after the law passed, all of the state’s top 10 largest cities now have at least one entertainment district, and dozens of smaller cities have embraced them as well.

“There’s not really a way for us to measure economic impact of entertainment district events specifically,” said Megan McGowen Crouch, city manager for fast-growing Auburn, which has one entertainment district in its downtown area.

“It’s certainly part of bringing people downtown for events, and of the business our downtown restaurants can do during those events,” she said. “It contributes to the atmosphere of events, allowing people to gather outside – during events with or without street closures – to enjoy downtown.”

Modeled on the French Quarter

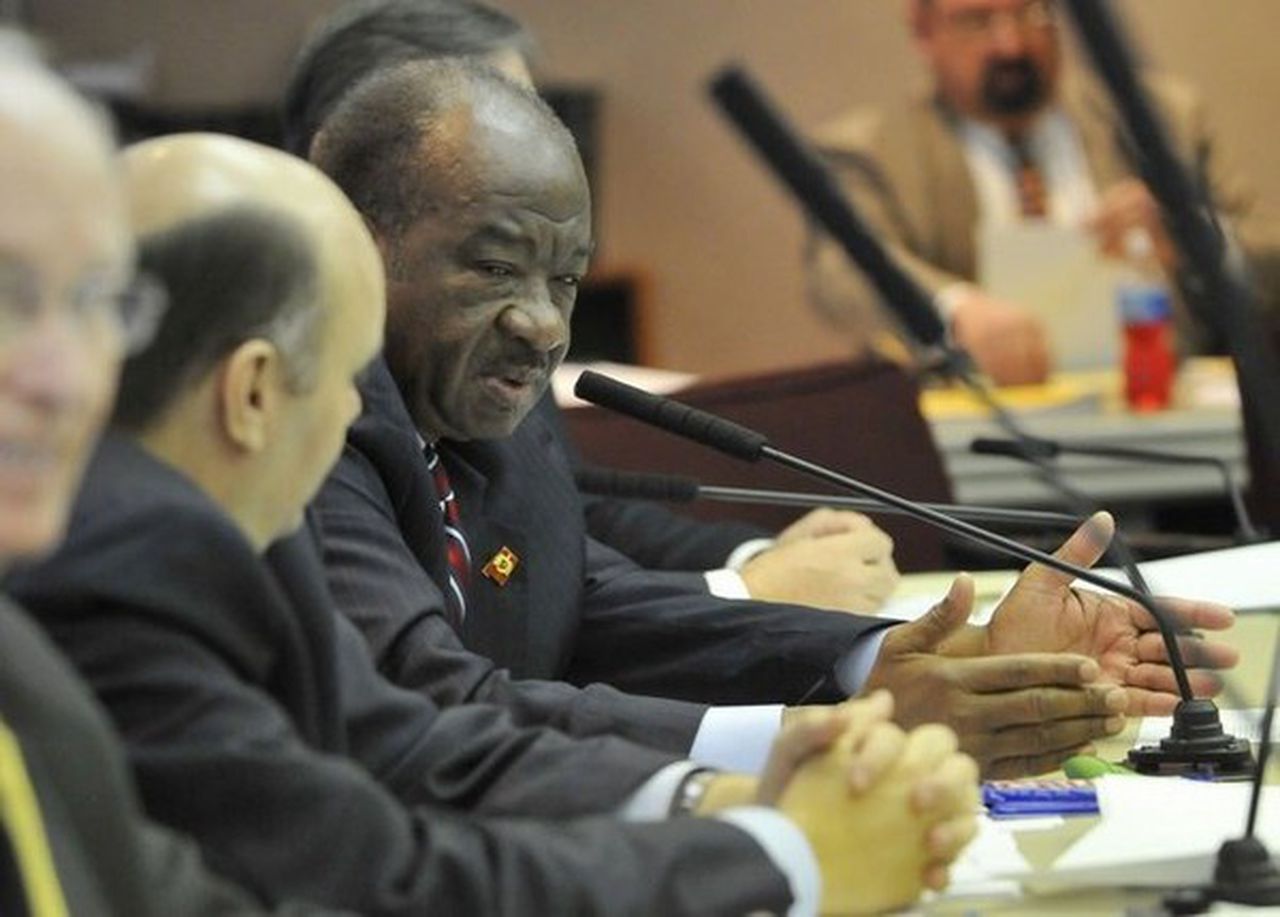

Former State Rep. James Buskey, D-Mobile, who retired in 2017, was among the chief sponsors of the entertainment district bill in 2012. (file photo)

The districts originated through bipartisan support in the Alabama Legislature in 2012. Retired State Rep. James Buskey, D-Mobile, and state Rep. Terri Collins, R-Decatur, were the chief sponsors of the legislation that was eventually signed into law by former Gov. Robert Bentley.

Buskey said before the legislation was introduced, he erroneously thought Montgomery already had an entertainment district near Riverwalk Stadium.

“My thinking was an entertainment district would pattern itself in what exists in the French Quarter in New Orleans,” said Buskey, who retired from the State House in 2018, following a 42-year legislative career. “That was the idea of introducing the bill.”

He said Mobile’s 2013 approval of its two entertainment districts – located on two separate sides of Dauphin Street – provided an outline for other districts around the state.

“Evidentially, it must be working,” he said, looking back now on the changes since 2012.

Mardi Gras crowds in the French Quarter are seen in the rain from the balcony of the Royal Sonesta Hotel in New Orleans, Tuesday, March 4, 2014. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Collins said she recalls initial pushback over concerns that Alabama cities, through outdoor alcohol consumption, would see some of the excesses of Bourbon Street – the famed New Orleans street lined with bars, strip clubs and mass gatherings during festivals like Mardi Gras.

“That’s not happened,” Collins said. “It’s been family-friendly and opened up opportunities to be outside and it’s been a positive thing in my community where I go an experience it.”

‘Times Square’

Indeed, the experience in Decatur has led to new festivals, street parties and a surge of economic activity.

Decatur Mayor Tab Bowling points to $70 million in downtown projects that can be linked to the entertainment district in the heart of the city’s downtown along Second and Moulton avenues.

“That would be Times Square for us,” he said.

The developments include a Fairfield Inn and a dormitory for the Alabama Center for the Arts that can house up to 125 people. “Their guests eat in our restaurants, and enjoy our bars. It’s the same thing with the dorms.”

Festivals and parades have since emerged, as has the popular 3rd Friday season that runs from April to October featuring car shows, music, and street vendors.

Decatur hosts an annual Mardi Gras parade that supports the Carnegie Visual Arts Center. The mayor also touts the city’s Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration that occurred in November as a “huge success.”

“All of them are held inside the district, and that lends itself to be able to go in and, if you like, grab an adult beverage and go out and enjoy the events taking place in the downtown areas as opposed to being inside a restaurant,” said Bowling.

“The community comes together with family and friends,” he said.

Public safety concerns

The scene along Dauphin Street during the morning hours of Sunday, January 1, 2023, in the location where a shooting occurred around 11:14 p.m. on Saturday, December 31, 2022, that left a 24-year-old man dead and 9 others injured. Those injured were taken to area hospitals. They range in ages from 17-57, according to Mobile police. Two businesses were also damaged during the shooting. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Bowling said there have been few public safety worries within the district. The same thing can be said in Huntsville, and other cities where the districts are found.

But two recent shootings in downtown Mobile sparked talks about shutting down the entertainment district earlier, moving up its current midnight closure to 9 p.m. That proposal, however, did not go anywhere.

The potential for violence is one of the reasons why the Alabama Citizen’s Action Program (ALCAP) opposed the original legislation, said Greg Davis, president and CEO of an organization that advocates on behalf of thousands of churches in Alabama.

He said the group “anticipated the very problems that have arisen,” added that “the more we normalize and promote alcohol use,” the more problems will arise.

“City leaders boast about the revenue these district produce, but they all ignore the costs like increased police expenses, and the seemingly inevitable social pain and even loss of life from the results of drunkenness,” Davis said. “It’s not that difficult to connect the dots.”

Related content: A place where ‘drunks hang out’? Alabama cities still struggle with open container quandary

In Tuscaloosa, the January 15 shooting on The Strip sparked attention to an area in the heart of the University of Alabama’s campus community that has been eyed before as an entertainment district.

Killed in that shooting was 23-year-old Jamea Harris. Arrested was 21-year-old Darius Miles, a junior reserve forward for the Crimson Tide basketball team who is accused of providing the gun in the slaying.

Tuscaloosa City Councilman Lee Busy, who represents the university area and The Strip, said there are two sides to the entertainment district discussion: One is the economic benefits and vibrancy they bring to a city. Tuscaloosa’s sole entertainment district is located downtown along the banks of the Black Warrior River.

But the other side, he said, are the public safety concerns of “pouring enough people and enough alcohol in a concentrated area” that will lead to “alcohol-driven events.”

Busby said those concerns are not exclusive to entertainment districts, adding that the city’s existing district is “successfully spawning art galleries” and has a community theater and fine dining establishments, upscale hotels, and cigar shops.

He said that any interest in creating a new district within The Strip is a no-go despite what he said was “understandable” interest shown by university students.

“We’ve been approached in the past for designating The Strip as an entertainment district,” he said. “We’ve declined to do that. We continue to think that it is the absolute right move.”

He added, “If I was a student, I would have wanted the entertainment district to expand to the Strip so I could walk up and down the street with an open container.”

Mobile city officials do not appear to be enacting any extra restrictions in the heart of its entertainment district ahead of its annual Mardi Gras celebration. At least one bar owner, however, has called for more restrictions following the New Year’s Eve shooting that left one person dead and seven innocent bystanders shot.

Related: Mobile mayor: ‘Everything’ under consideration for securing downtown Mobile after New Year’s Eve shooting

In November, a shooting within the district occurred at the Paparazzi nightclub resulting in four injuries. Mobile Police Chief Paul Prine said he plans to have the agency’s entire force of more than 400 police officers on patrol and visible throughout the Carnival season.

But the district continues to be an attractive place for activity highlighted by the monthly Art Walks, which have grown from a sleepy wine and cheese outing 10 years ago into a present-day street festival.

“I think it’s helped to create a better experience for our patrons, both locals and visitors,” said David Rasp, owner of Heroes Sports Bar & Grille in downtown Mobile. “I think if properly managed, I don’t see a downside to the entertainment district or its guidelines.”