The ugly turn Birmingham took after its founding

David Sher’s ComebackTown for a better greater Birmingham

Click here to sign up for newsletter. (Opt out at any time)

Today’s guest columnist is Bill Ivey.

There’s no way to understand Birmingham until you know its history.

Slavery was never practiced in Birmingham because it wasn’t founded until 1871, six years after the Civil War.

But after its founding Birmingham took an ugly turn.

Convict leasing was a system through which “convicted criminals” were leased by states to private individuals and companies–who were free to work the convicts as they saw fit.

And, although all the former Confederate states utilized the system, it was worse in Alabama. Let’s examine why it was so bad in Birmingham–and how that legacy is still relevant. We have never grieved over this great injustice because we don’t know about it. It’s time to change the narrative.

Today, countless folks in our area are helping to make this a much better place to live. They are the spiritual, civic, and political descendants of Dr. Fred Shuttlesworth and David Vann. Downtown is becoming cool. Birmingham receives national recognition for its food, tech sector, new downtown attractions, parks, and so on. But I think we are missing something massively important that is impeding our progress, so stay tuned until the end.

Birmingham: The Southern Outlier

For two reasons, Birmingham is unique among all large Deep South cities. It is the only one founded after the Civil War (1871). And, unlike other regional cities that were built on transportation and trade, Birmingham was founded on mining and manufacturing.

Post-Reconstruction Alabama

Imagine the scene in Alabama in 1874 when Union troops withdrew and Reconstruction essentially ended. The Civil War had taken the lives of 35,000 Alabamians and severely wounded 30,000 more–approximately one in four adult males killed or wounded. The 2022 equivalent would be almost 400,000 statewide casualties.

Alabama was devastated. And long-term “reconstruction” was a travesty, a myth. Former Union leaders were generally as prejudiced as former Confederate ones. So Northern politicians and businessmen quickly turned their attention to their exploding industrial economy. And turned their backs on the old Confederate states.

Widows and orphans were all too common in Alabama. Most people–White and Black–lived in desperate, dire poverty. Alabama’s agrarian economy was a disaster. With a couple of generations of White men devastated by the War, how could the survivors move forward? More than 400,000 Blacks, almost half the state’s population, were free. How could the state rebuild its economy after losing its labor force? And, last, how would Alabama manage the collective White fears aimed at a huge number of free Blacks?

The War and “Reconstruction” had temporarily thrown state politics into chaos. Where would tax revenue come from to support a fragile state government? How would Alabama’s power brokers manage the new national framework and rebuild their state political structures?

Keep in mind that, before Emancipation, Blacks weren’t included in the formal criminal justice system. They were either unjustly punished by slave owners or killed/lynched for alleged crimes by local mobs. Now the local and state governments of Alabama had to take on that responsibility, with little tax revenue to support those efforts.

The main challenge for any government is to find a balance between liberty and order. Alabama chose order. Whites were so terrified of the free Blacks that they built “legal” walls around Black communities. Southern Blacks were caught in a horrific web; they lived in what we would understand as a police state.

The old Slave Codes were converted into the Black Codes after the War. Among other things, the Codes criminalized joblessness for Blacks, forced them to sign annual labor contracts that ensured they received the lowest pay possible for their work, and denied them the right to vote (despite the 15th Amendment). Without proof of employment or a place of address, Blacks could be fined or jailed. Loitering and vagrancy were crimes, but Alabama made it nearly impossible for Blacks to find work or own property. And then punished them for idleness.

The Convict Leasing System

Such conditions allowed a great conspiracy to become possible: Alabama passed laws authorizing state prisoners to be leased to private industries. Most of those prisoners would be Black.

Even before the War, Alabama was desperate for revenue–and one way to minimize expenses and maximize revenues was to lease White prisoners to private companies and individuals (under the authority of a state warden). Also, beginning in the 1860s and 1870s, county prisoners were leased to small factories and the state-owned farm. Local sheriffs made money off of these arrangements.

Social and political conflicts, poverty, and a racist legal system led to a growing number of Black prisoners. Naturally, the importance of the state penitentiary in Wetumpka and local jails increased tremendously during those years. With little tax revenue, how would such facilities be funded?

And–with the state economy in shambles–how could the state budget be funded? Birmingham, the New South city, provided the answer and thereby became the centerpiece of the story.

Convict Leasing in Birmingham

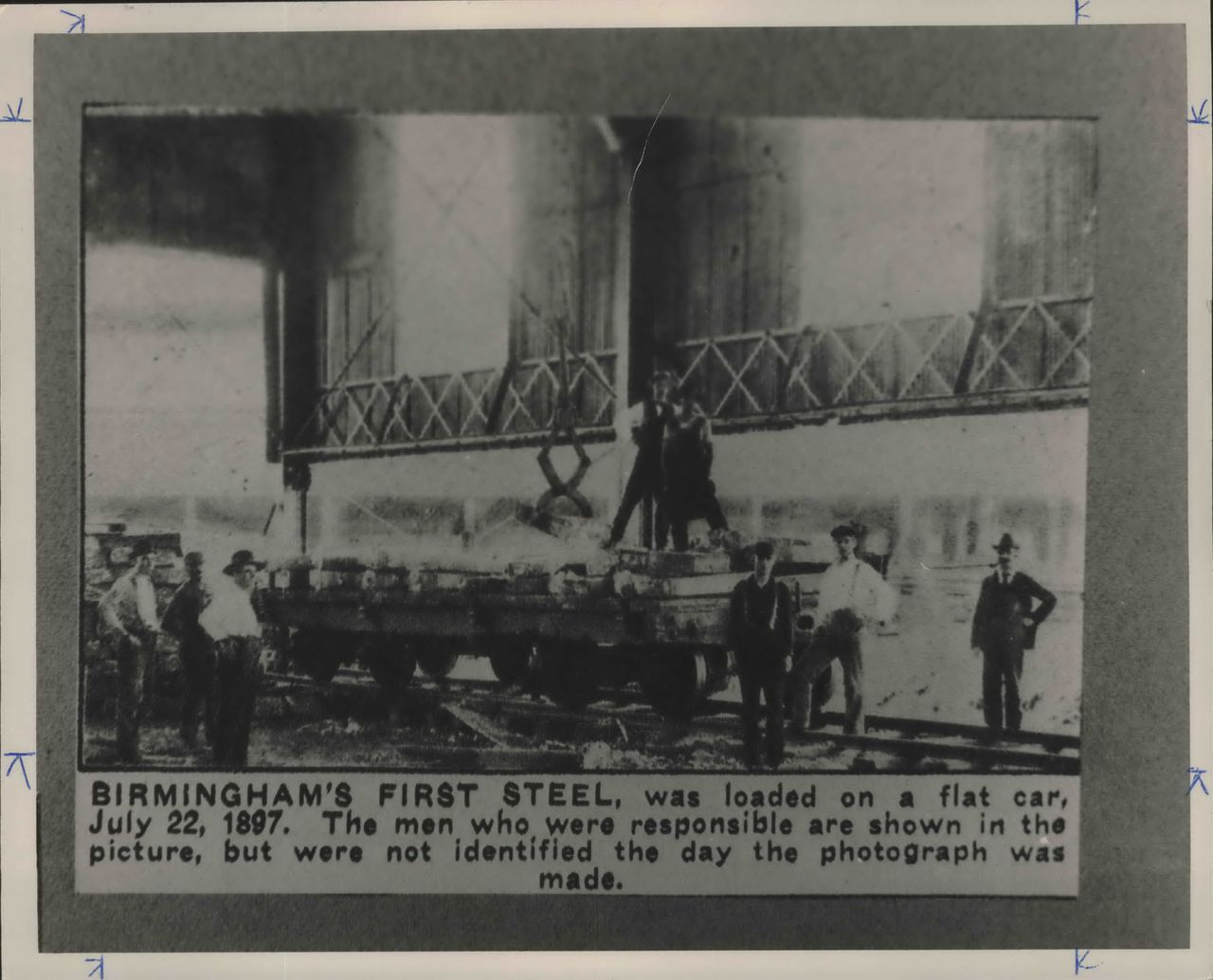

Birmingham was the only place in the U.S. that included the three essential ingredients for steel production: coal, iron ore, and limestone. Outside investors were drawn to the area and by the late 19th Century, iron manufacturing became the most important industry in Alabama. Steel production soon followed.

Due to incredibly fortunate timing, as Alabama’s old agrarian economy was shrinking, Birmingham was exploding as a Southern industrial and mining hub. This perfect storm fueled Alabama’s New South economy. The state became the leading industrial center in the Deep South–and one of the hottest in the country.

Birmingham, however, was faced with a severe labor shortage. Many people in rural central Alabama migrated for those jobs. In smaller numbers, so did agricultural workers from a wider radius, including men from other states. In addition, immigrants came from Europe–5000 by 1890. But it was not enough.

The state government was desperate for revenue and Birmingham needed cheap laborers. The solution came from an unholy alliance between the state’s still-powerful Black-Belt landowners and the new-money Birmingham industrialists, known as “Big Mules.” The Big Mules would lease as many convicts as possible.

This is no Cool Hand Luke story; convict leasing was a horrific solution. One of the least understood and most dangerous systems of Black oppression in the post-Civil War South, it fueled the explosive growth in Birmingham and allowed the state government to survive.

For Birmingham’s Big Mules, the convicts–mostly Black–provided an ideal workforce. They were cheap and docile, and their numbers helped the companies to suppress the union movement. And, as a result, White miners had no leverage. Diane McWhorter succinctly captured the plight of White miners in her epic history of the Birmingham civil rights battle, Carry Me Home: They “were cheated on the coal they mined…on the rents they paid…at the company store, and summarily fired at the hint of complaint or union activity.”

The Birmingham Monopoly

In 1883, convict leasing provided about 10% of the state’s total revenue–a staggering amount of money. That year, however, everything changed. The legislature approved a plan to lease thousands of prisoners to three Birmingham companies: Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad (TCI); Pratt Coal and Iron (which TCI purchased in 1886); and Sloss Iron and Steel. Birmingham had gained a monopoly on the leasing of state convicts, 90-95% of whom were Black. The companies built and maintained unregulated prisons at various mine sites around the city.

In 1888, however, TCI negotiated a 10-year contract to lease all able-bodied state prisoners. The company paid the state $9-18.50 per month for each prisoner; the scale depended on their health and abilities. Astonishingly, by 1898, the percentage of state revenue derived from convict leasing had increased to nearly 73%. The Big Mules became very wealthy from the forced, practically free labor of mostly Black prisoners.

The working and living conditions were inhumane and often deadly. Prisoners were sent into mines with poor equipment and little if any training. They were exposed to dangerous conditions such as high gas levels, flooding, falling rock, and unstable explosives. Mine bosses had no incentive to treat the convicts well; with increasing quotas, they were motivated to literally work the miners to death.

The mine managers forced the prisoners to eat terrible food, exposed them to communicable diseases (especially tuberculosis and pneumonia), and supplied them with contaminated water–among other horrible conditions. Beatings and torture were common.

McWhorter: “…Negroes were the cornerstone of their (Big Mules) industrial success. Segregation–with its sentimental life force, racism–had kept their workers divided, wages depressed. The industrialists had not invented segregation, but they had honed it into the ultimate money-making instrument.”

U.S. Steel Moved In

In 1907, U.S. Steel acquired control of TCI–essentially turning Birmingham into an economic colony of Pittsburgh. They continued to use prisoners for the next five years. By 1910, as many as 5,000 state and county prisoners were leased at any given time. Thousands of Black men sentenced to less than a year were being cycled through the system. The threat of arrest under trumped-up charges, followed by almost immediate forced labor in Birmingham, had become an all-too-familiar part of Black life in many rural areas.

In 1911 an explosion at the Pratt Consolidated Coal Company Banner Mine (a TCI/U.S. Steel subsidiary mine located in northwestern Jefferson County) killed 128 men. Of the 128 dead, 114 were Black and 14 were White. 123 were convict workers and 5 were free (2 Whites and 3 Blacks). The Banner Mine explosion still ranks among U.S. history’s 15 deadliest coal mine disasters.

U.S. Steel, possibly the largest company in the world at that time, continued to utilize convict labor after 1907 Even with all the deaths on their watch between 1907 and 1912, the company has never taken responsibility. And Alabama was addicted to the convict leasing system: from 1907-1910 the state earned a profit of $1.3 million (about $43 million in current dollars).

In 1912 U.S. Steel announced that it would employ only free workers in its mines. The state then took over the management of the convict leasing system, prompting several legislative efforts to end the practice during the ensuing 16 years.

Although the Banner Mine disaster led to protests and negative national publicity, Birmingham’s Big Mules were able to fend off legislative attempts to end convict leasing and increase mine safety. Alabama had maintained the nation’s longest-running convict leasing system, from 1866 until 1928. Florida, the next-to-last state, had ended theirs in 1923.

Why Bring It Up Now?

A couple of years ago I was fortunate to be present at a brief presentation by Dr. Max Michael, former Dean of the UAB School of Public Health: Urban Blight Effects. I was stunned to learn that the effect of urban blight (high blood pressure, kidney disease, PTSD, for example) can be carried by DNA into at least the next two generations. Dr. Michael’s insights led me to research the keywords and into a scientific field I’d never heard of: Epigenetics.

Here’s a shorthand version of what I learned:

- A growing body of research suggests that trauma (childhood abuse,

- family violence, food insecurity, etc.) can be passed from one generation to the next.

- Trauma can leave a chemical mark on a person’s genes, which is passed down to future generations.

- This mark doesn’t cause a genetic mutation, but it does alter the mechanism by which the gene is expressed. (Therefore not genetic, but epigenetic)

I’m at best an amateur social scientist, but this lightning bolt from Dr. Michael, this “epiphany,” gave me a new perspective on our community. If convict leasing ended in 1928, is it not likely that many of the descendants of those men still live in our area? And wouldn’t they carry (genetically and through family stories) the residual horrors of their great-grandfathers, grandfathers, and even their fathers? Keep in mind that scientists believe that these epigenetic effects may be carried beyond two generations; they just can’t prove it yet.

And this is not just a racial conundrum. What about poor Whites who were also exposed to violence and horrible working conditions? Who were denied the opportunity to join unions because there was always an available supply of virtually free Black labor? Who also lived in squalor? How have such conditions affected their descendants?

What Can We Do?

What we need in the Birmingham metro area is a scaled-down version of the Marshall Plan.

The U.S. learned a hard lesson after World War I: Don’t leave your defeated enemies living in political and economic chaos. Hitler rose out of those ashes and started World War II in Europe.

So after World War II we implemented the Marshall Plan. In a now-celebrated speech delivered at the Harvard University commencement on June 5, 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall proposed a solution to the widespread hunger, unemployment, and housing shortages that faced Europeans in the aftermath of World War II. We spent $13.3 billion (about $163 billion in current dollars) to rebuild our enemies and restructure their economies. Unbelievable after what the Fascists and Nazis had done–but we did it. And it worked.

Here’s my second epiphany: There was no “Marshall Plan” for the defeated Confederacy. Except for a very brief, halfhearted, and ineffective “Reconstruction,” Union leaders left the Confederate states to fend for themselves. There was no reconstruction–and our region still suffers from that.

Our own “Marshall Plan” is not brain surgery. Figure out creative ways to work around the pathetic restrictions of our 1901 Constitution. Raise billions of dollars. Lift up poor Blacks and Whites. Eradicate substandard housing. Create the best public transportation system in the country. Build a high-tech economy to include some new Fortune 500 companies. Recruit educated employers and employees. We need a Richard Shelby-type “czar” to run the show, to kick the apathy and pettiness out of the region. We would become THE model, the most famous and admired metro area in the country.

Let’s not discuss why we can’t do this.

Bill Ivey is a retired coach and History/Government/Economics teacher who has a BS in Business from the University of Alabama and a Master’s degree in History from UAB. He coached basketball and track for 25 years, including a 3-year stint as the women’s basketball coach at UAB. After retiring from the public school system, he founded a nonprofit that assisted young male basketball players who had graduated from high school but had “slipped through the cracks.” He also founded and ran the Birmingham Basketball Academy until 2020. He and his wife Cathy lead the Carolyn Pitts Class for Social Justice (Sunday School), which meets online every Sunday morning.

David Sher is the founder and publisher of ComebackTown. He’s past Chairman of the Birmingham Regional Chamber of Commerce (BBA), Operation New Birmingham (REV Birmingham), and the City Action Partnership (CAP).

Click here to sign up for our newsletter. (Opt out at any time)