Will Mobile, Baldwin counties be split into separate congressional districts?

Worries about splintering Mobile and Baldwin counties for the first time in over 40 years are building in coastal Alabama following the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling last week that a state congressional map likely violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The high court’s 5-4 ruling will likely cause the state to create a second majority Black congressional district, and the potential looms large for at least portions of Mobile and Baldwin counties to be split for the first time since the 1970s, despite close economic ties between the state’s only two coastal counties.

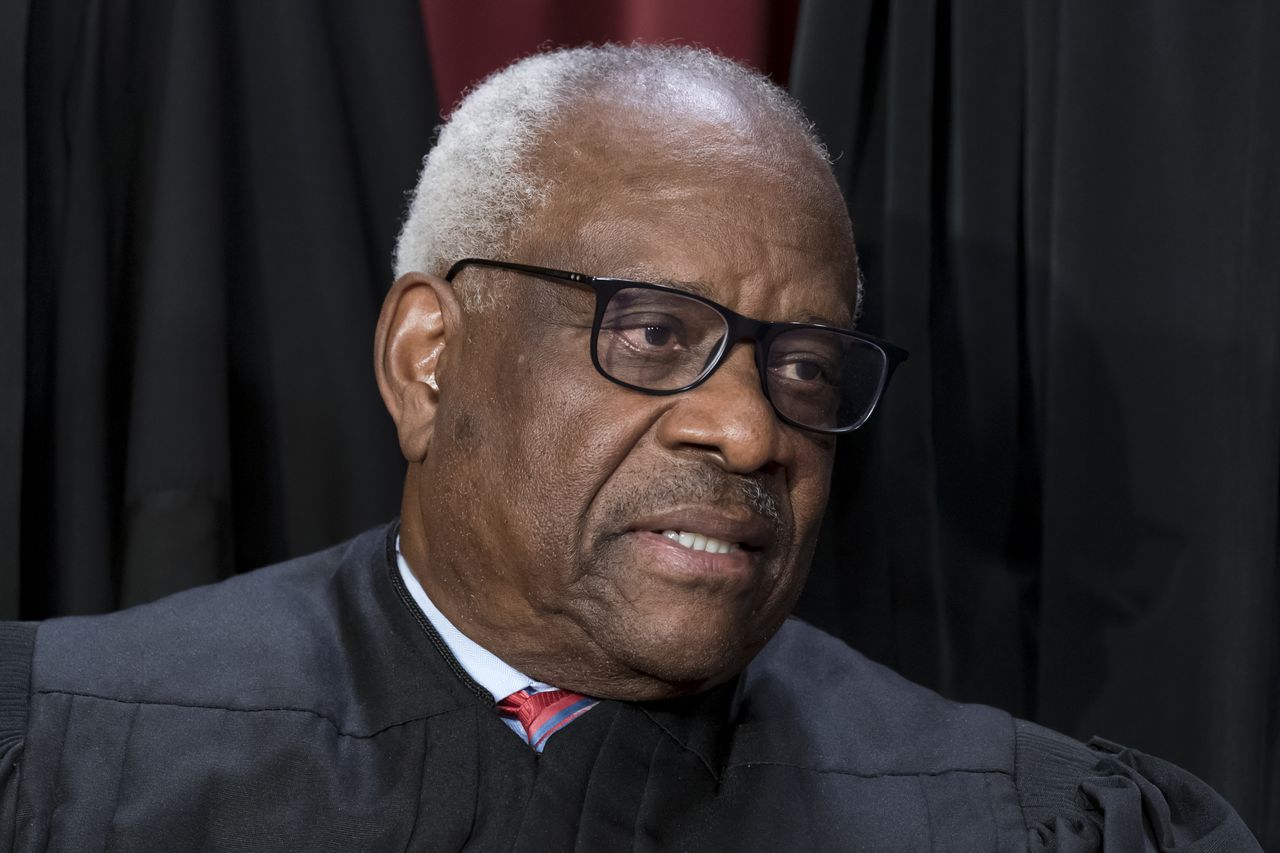

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas joins other members of the Supreme Court as they pose for a new group portrait, at the Supreme Court building in Washington, Friday, Oct. 7, 2022. Justice Thomas was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Justice Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1991. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)AP

In fact, the possibility of splitting the two counties factored heavily into the Supreme Court’s written opinions, as Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed the concerns and Justice Clarence Thomas said they should be taken seriously.

“It is indisputable that the Gulf Coast region is the sort of community of interest that the Alabama Legislature might reasonably think a congressional district should be built around,” wrote Thomas in his dissent.

But Roberts, writing for the Court, found that some region has to be split up so others can be united. “Even if the Gulf Coast did constitute a community of interest, moreover,” Roberts wrote, “the District Court found that plaintiffs’ maps would still be reasonably configured because they joined together a different community of interest called the Black Belt.”

Related content:

A similar divide can be found along partisan lines in Alabama. Republicans are voicing worry about dividing the two and limiting the ability to coordinate concerns along Alabama’s coast. But Democratic politicians and activists are not as concerned, saying that Mobile and Baldwin counties do not share similar political interests.

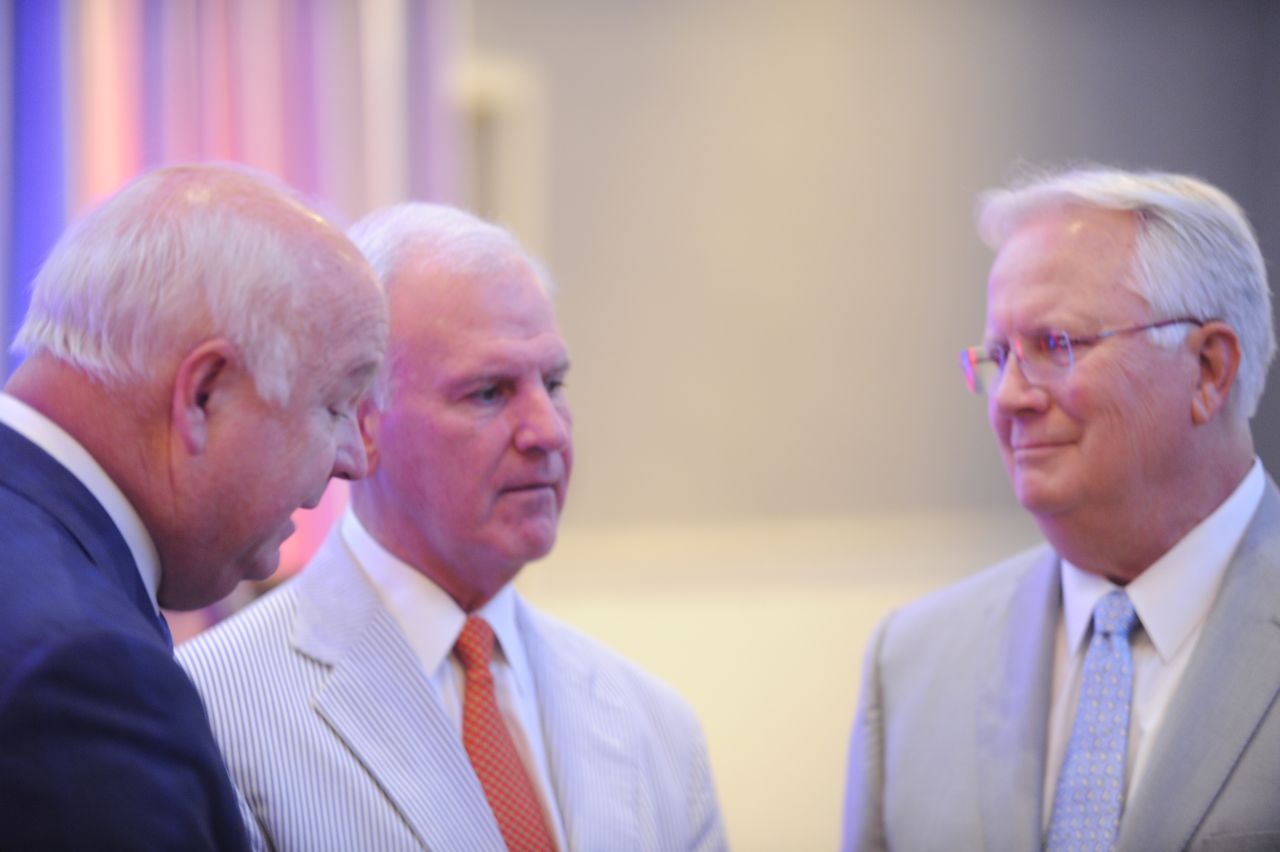

“I am worried,” said Bradley Byrne, president & CEO with the Mobile Chamber who served as the representative for the 1st congressional district from 2014-2021. “You could have a (congressional district) from Tuscaloosa to Mobile or Mobile to Dothan. Imagine someone from Tuscaloosa covering that whole area and understanding Mobile as well?”

“Everything is possible,” said Alabama Sen. Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro, a member of the state commission charged with drawing the map. “Mobile is in play (for changes). Possibly Birmingham to the north is in play.

“What you have to do is pick up substantial Black voters from those two areas to come up with the 500,000 people who need to go into a district and meet all the other criteria of the courts.”

Communities of interest

Three congressmen gather on Wednesday, August 3, 2022, at the Battle House Renaissance Hotel & Spa in downtown Mobile, Ala. Pictured from left to right are former Alabama 1st congressional district Reps. Jo Bonner (the current president at the University of South Alabama) and Bradley Byrne (president and CEO with the Mobile Chamber) and current U.S. Rep. Jerry Carl. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Spanish Fort Mayor Mike McMillan recently traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with current 1st Congressional District U.S. Rep. Jerry Carl, R-Mobile, to discuss the potential of bringing back a post office to his fast-growing Baldwin County city.

The meeting with U.S. Post Office officials, McMillan admits, might not have happened if the congressional district representative lived in the Wiregrass – hundreds of miles away and closer to the Florida Gulf Coast than Alabama’s coast.

“That is no comforting feeling for me as mayor,” McMillan said. “(Wiregrass politicians) don’t recognize the issues we fight for every day. And it goes both ways. Jerry Carl might not recognize the fights in the Wiregrass.”

Sprawling Baldwin County, over the past 52 years since the 1970 Census, has grown by over 314 percent, but remains an overwhelming white county. The 2020 Census shows only 8.6% of the county’s population as Black. The more urban Mobile County, home to Mobile City and the state’s port, by contrast, is 37% Black.

Officials closest to the redistricting process including state Rep. Chris Pringle, R-Mobile, say it’s too early to fret. But others, like the two most recent former congressmen of Alabama’s 1st district, are sounding alarms.

Their comments echo those of Justice Thomas who, in his dissent, wrote that moving Black Mobilians who reside “in the heart of District 1″ into a newly-formed Congressional District 2 will upend a long-standing “community of interest” in the Gulf Coast region.

Alabama’s 1st congressional district currently includes Mobile, Baldwin, Washington, and Monroe counties as well as parts of Escambia County. The voting age population is 67% white and 25% Black, but most of those Black residents live in Mobile County.

Truck traffic along Interstate 10 near the U.S. 98 exit in Daphne, Ala., on Thursday, March 25, 2021. A $2.9 billion overhaul to the I-10 Bayway between Mobile and Baldwin counties and the construction of a new bridge in Mobile is considered the largest transportation project in Alabama history. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Jo Bonner, president of the University of South Alabama who was the district’s congressman from 2003-2013, said lumping a congressional district that includes Tillman’s Corner near the Alabama-Mississippi state line to the Dothan region will complicate major economic policy initiatives like the Interstate 10 Mobile River Bridge and Bayway project that connects downtown Mobile to Baldwin County.

“The Bridge is $3 billion,” Bonner said. “Is that a priority for someone if they live in Enterprise? It is hard for to think that it will be a top priority. Or will four-laning the Ross Clark Circle (in Dothan) be a top priority for someone in Mobile?”

Democrats: Differences exist

A “Black Voters Matter” rally took place on Friday, October 16, 2020, next to Mardi Gras Park in downtown Mobile, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Democratic lawmakers and officials near the coast view things differently and are joining voting rights activists in applauding this month’s Supreme Court ruling.

They do not view Mobile and Baldwin counties having similarities aside from geography and proximity. The biggest split, they note, is that Baldwin County consists entirely of Republican politicians while Mobile County is more varied. The City of Mobile and Prichard, which are majority Black, are represented almost entirely by Democratic lawmakers in the Alabama Statehouse.

“There are significant differences we see at election time, and there are significant differences between the City of Mobile and Baldwin County in terms of interests that show up in voting patterns,” said Ben Harris, chairman of the Mobile County Democratic Party. “I think there is a compelling interest in putting Mobile into those (majority-minority congressional) districts. It gives opportunities for voices that have traditionally been suppressed to be heard and we look forward to that opportunity if we get it.”

Sen. Vivian Davis Figures (D-Mobile) speaks to a colleague during the first meeting of the Alabama Senate for the 2023 legislative session in Montgomery, Alabama. AL.com/Sarah Swetlik

State Sen. Vivian Figures, D-Mobile, said while it’s too early to tell how the districts will be drawn, she is pleased with the court’s ruling and the potential for more minority representation for Mobile which has become more majority Black over the past 20 years.

“We need more minority representation,” she said. “We live in a state where there are no Democratic or African American nor minority, period, elected to any constitutional office in the State of Alabama. All of our State Supreme Court, Appeals Court, all of them are Republican and while males and white females.”

She added, “That is not the makeup of this state. Even in a county like Mobile with all of the minority population we have here, and we don’t have one minority nor Democratic judge on the District or Circuit level.”

Justice Roberts put it rather plainly: “Alabama argues that the Gulf Coast region in the southwest of the State is such a community of interest, and that plaintiffs’ maps erred by separating it into two different districts. We do not find the State’s argument persuasive.”

Robert Clopton, president of the Mobile County chapter of the NAACP, agreed, saying he doesn’t believe Baldwin County needs to be adjoined to Mobile County. He said he believes Baldwin County, now the state’s fourth-largest county and adding an average of 19 residents per day, “has its own autonomy.”

Said Clopton, “Are they similar? They are on the coast. They work together and do a lot together. That is important. But there are so many differences between Baldwin and Mobile. I will be curious to see how these line will be drawn.”

‘Obnoxious’ split

The concerns from Bryne and Bonner, both Republicans, are shared by other GOP officials and conservatives in the region who believe Mobile and Baldwin counties should be left together if redistricting occurs anew.

“It is constitutionally, statutorily and morally repugnant for the Court to say that a Black voter in Mobile has less in common with a white voter two blocks away than he does with a voter of either race 200 miles away at the Georgia state line,” said Quin Hillyer, a Mobile resident and a conservative columnist for The Washington Examiner.

“Thomas got it right,” he added. “He put it very plainly that it’s patently obvious the two coastal counties form a community of interest and it’s a very strong one because of geography, being on the coast, and because of the (Alabama State) Port, the beaches and the rivers. Anyone who lives in Alabama knows that the coastal counties are thought of as one entity. To split them is obnoxious.”

Patrick McWilliams, vice-chairman of the Baldwin County GOP, said splitting the two counties will be detrimental to economic development.

“From the manufacturing and business standpoint,” said McWilliams, “it should all come under one congressional district on what we are doing here whether it’s aerospace, tourism or agriculture.”