Who will step up in fight to save our nation’s oldest free Black settlement?

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. – Standing outside a weathered century-old white ranch home with a dilapidated roof, Julie Moody Lewis peers through a glass door and points to the interior of the ailing structure, which is covered in floodwater and so overrun with mold no one can enter. But the historian says she’s determined to preserve and rebuild this important piece of the past.

The site, located at 1538 Woodrow Rd. in Staten Island, N.Y., is the museum run by the Sandy Ground Historical Society, which has preserved two centuries worth of rich culture – one that is a significant part of American history.

“There is a broken water pipe in the museum, and we cannot even get in there to fix it. The city can’t turn off the water. They said we have to get a plumber. But we don’t have the money to get a plumber,” said Moody Lewis.

The structure is part of Sandy Ground (first known as Harrisville, Africa and Little Africa), which is the nation’s oldest free Black settlement still inhabited by descendants of the original settlers.

The Sandy Ground Historical Society Museum, which is in great need of repair. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

The first recorded Black landowners were Moses K. and Silas K. Harris, brothers from New Jersey who initially came to the area to work as gardeners in the 1820s. Sandy Ground began to populate in the 1850s when African-American oystermen from Maryland were attracted to the area because of the abundant oyster beds of the Raritan Bay, a body of water that exists between New York and New Jersey. Soon, Sandy Ground became a community where African-Americans found prosperity and freedom from persecution.

But today the community looks different. The wooded areas, sandy ground for which the community was named, sprawling farmlands and strawberry fields have been replaced with rows of homes, concrete, asphalt, a crowded strip mall and two public schools.

In December 2021, the community showed up on a national cultural landscape report deemed “threatened and at-risk.”

And some say the community could be completely erased if the Sandy Ground Historical Society isn’t able to rebuild its crumbling museum, find a new executive director and raise much-needed funding to revitalize its operations.

Julie Moody Lewis, president of the Sandy Ground Historical Society holds up pictures of relatives on the grounds of the museum on Staten Island, N.Y. Tuesday, Jan. 31, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

“We need support. We want people who are loyal to the organization, loyal to the history. … We are not going to let this history go,” said Moody Lewis, who is president of the Sandy Ground Historical Society and can trace her heritage back to one of the community’s founding fathers.

“We are being challenged. The times are changing. We have done a lot of work to lay this history out. This is an authentic historic site. And we want to make sure it stays here. It is an important part of Staten Island history, New York State history, national history,” she added.

Julie Moody Lewis, president of the Sandy Ground Historical Society and Cacia Watkins, a descendant of the original settlers, hold up pictures of a quilt depicting the rich strawberry fields that once existed in Sandy Ground. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

SANDY GROUND TODAY

If you park your car and walk through this modern bustling community, look closely and you’ll see remnants of the past.

There are several properties in the community designated New York City landmarks: two tan clapboard Baymen’s cottages, which are 120-year-old-plus homes once owned by the prosperous oystermen who settled in the community in the 1850s; the A.M.E. Zion Church, built in 1897; the Rev. Isaac Coleman and Rebecca Gray Coleman home; and the Rossville A.M.E. Zion Church Cemetery — a peaceful respite where both weathered and newer headstones tell the story of the community’s pioneers who once lived, worked and thrived there.

The roof of the Sandy Ground Historical Society Museum needs to be replaced. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

While there are less than 10 families who are descendants from the original settlers still residing in the community, there are hundreds of people who can trace their roots back to Sandy Ground.

CARETAKERS OF THE COMMUNITY

Founded in 1979, the Sandy Ground Historical Society plays the role of caretaker of the community’s history. Moody Lewis and her mother, Sylvia Moody D’Alessandro — who was born and raised in Sandy Ground and is executive director of the organization — have tirelessly worked to keep the history alive.

“The whole history of African-Americans was never told. And we’re talking about a community that started in the 1800s, and it was a positive community,” said D’Alessandro. “But you didn’t hear about it. So we felt we needed to tell that story. And so we did.”

With the help of other descendants, the mother-daughter team has documented oral histories, collected artifacts, preserved handmade quilts made by Sandy Ground residents, and helped get some remaining structures in the community designated as New York City landmarks.

Julie Moody Lewis and her mother, Sylvia Moody D’Alessandro, pose together at D’Alessandro’s home in New Brighton on Monday, Feb. 6, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

But the pair – both who have been honored locally for their forever dedication to preserving Sandy Ground – need help in their rebuilding efforts. The society’s board will soon be in search of a new executive director, as D’Alessandro, who is in her mid-80s, will be stepping down.

While Moody Lewis and D’Alessandro said they will always be involved in preserving Sandy Ground’s history for as long as they live, they implore the next generation to carry the torch forward to preserve the community’s legacy.

Sylvia Moody D’Alessandro, Nell Irvin Painter, Julie Moody Lewis, Deborah Moody-Collier, Peggi Currelley in 1998 at the Sandy Ground Historical Society luncheon celebrating Women in History Month

“Over the last few years, the board members aged, and some have died, and they weren’t being replaced by new people,” said Sheree Goode, a Sandy Ground board member.

“We have to keep this history alive,” added Goode, who is also first vice president of the Staten Island branch of the NAACP.

Said D’Alessandro: “We are bringing in the younger generation to make sure they know the history, and we are making sure they are prepared to go out and tell our story.”

The Baymen’s Houses on Bloomingdale Road are designated New York City landmarks and a part of Sandy Ground. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

But the organization needs more than a younger generation of historians.

Over the last several years and through the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Moody Lewis took a five-year leave of absence from the board, and during that time, the organization’s 501(c)(3) non-profit status lapsed.

In addition to regaining its non-profit status, the biggest obstacle for the Sandy Ground Historical Society is the rehabilitation of its museum, which needs a new roof, complete mold remediation, new plumbing and more, said Tom Wilson, a board member.

Photos of Sandy Ground’s early settlers line with lawn outside the Historical Society Museum. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

NEED FOR A BUSINESS PLAN

To move forward, Wilson said the organization needs a business plan, along with government funding.

“What has happened over the years, is the organization was not necessarily a functioning business. It’s made up of people who got together to form a historical society,” said Wilson. “It wasn’t corporately structured. It’s more grassroots than it has been a business. But for us to tell the story correctly and to preserve history, there has to be some business structure.”

Said Moody Lewis: “We understood that many board members worked as long as they could, and that the organization got to a certain level where we would have to transition into a business structure — one that utilizes all new technology. With COVID and everything else going on, we got kind of stymied.”

Julie Moody Lewis, president of the Sandy Ground Historical Society, reflects on Sandy Ground’s rich culture as she walks through the Rossville A.M.E. Zion Church Cemetery. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

HISTORIC ITEMS IN STORAGE

With the Sandy Ground museum uninhabitable, its contents now sit packed away in storage until the building is either repaired or completely rebuilt.

These items include: tin types of old photos from the 1800s of former residents; quilts made up of images from African culture; paintings by D’Alessandro of past Sandy Ground dwellers engaged in daily activities; exhibits with items that depict the self-sufficient way of life lived by pioneer settlers; documents; old publications, and an array of artifacts.

This photo was taken in May 1957 in Sandy Ground. Pictured from left are: Sylvia D’Alessandro, Shirley Moody, Shirley Sarjeant, Carol Logan and Etta Logan. (The identity of the child is unknown) (Courtesy of Julie Moody-Lewis)

HISTORY OF SANDY GROUND

After centuries of slavery, the New York State Legislature passed the Abolition Act on March 31, 1817. But slaves weren’t emancipated until July 4, 1827. Soon after, free Black communities were founded across the state. Sandy Ground is the third recorded community in New York where African-Americans owned land, according to city Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC).

A New York City Landmark, the Rossville A.M.E. Zio Church was erected in 1897 in Sandy Ground. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

It was in the 1820s when Moses K. and Silas K. Harris — two brothers from New Jersey who worked for wealthy Manhattanites as gardeners — purchased property on Staten Island and launched a lucrative farming business. The Manhattanites were said to have property on Staten Island, which led the Harris brothers to the borough, said Moody Lewis.

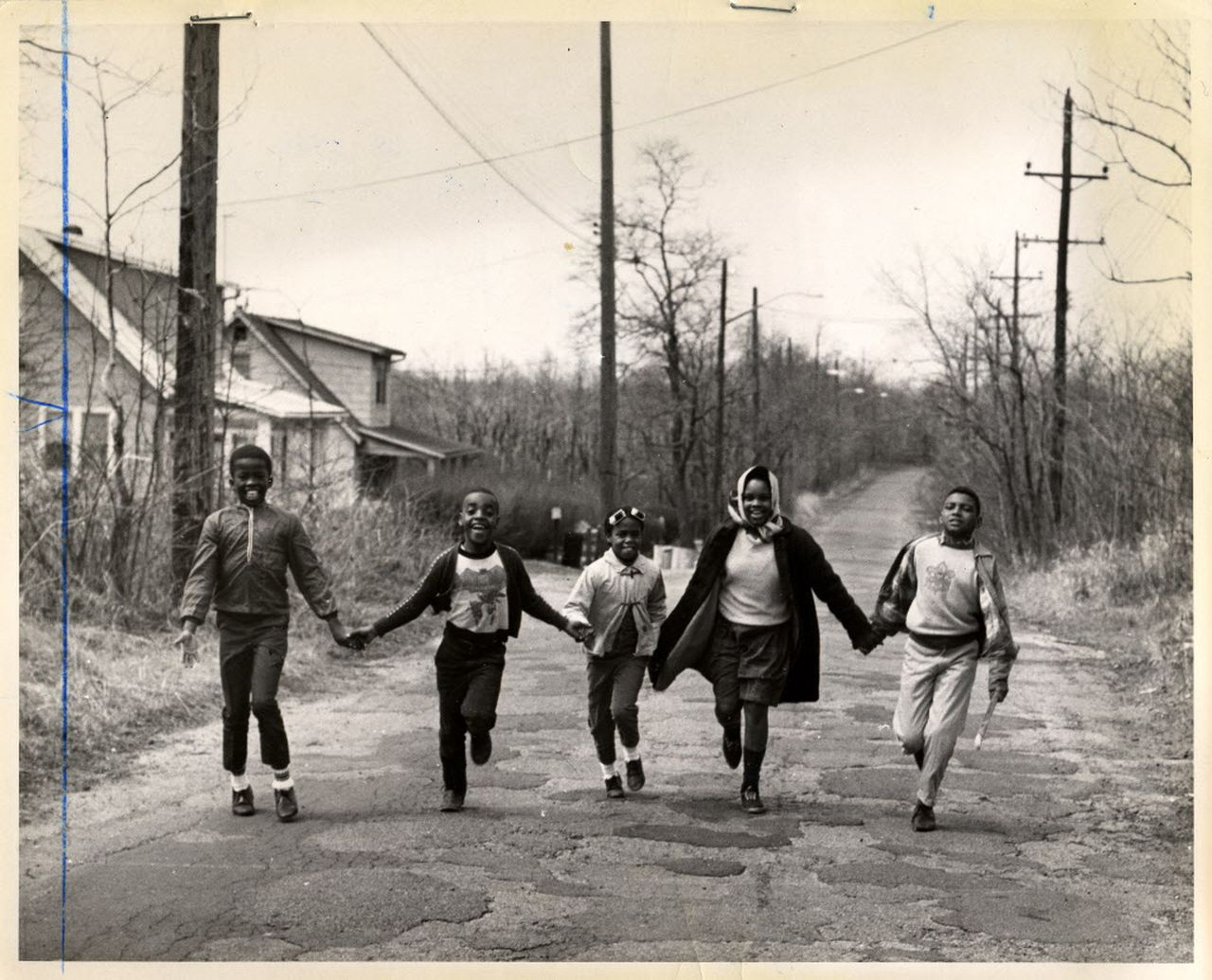

Children play in Sandy Ground in this photo from March, 1967. Considered the nation’s oldest continuously inhabited free Black settlement, the Staten Island land was recently deemed “threatened and at-risk” in a new national cultural landscape report. (Staten Island Advance)Staff-Shot

Hence, the area became known as Harrisville.

Before the Civil War began, a group of African-Americans from Snow Hill, Md., were drawn to the area because of the rich oyster beds that once existed off the shores of the Raritan Bay. The oystermen would travel back and forth by boat to dredge the waters around Staten Island.

A photo shows Lucille Herring, left, holding a t-shirt up to Elmore Taylor while Yvonne Taylor, sitting, and Marie Spicer and Sylvia D’Alessandro, right, look over other souvenirs of a Sandy Ground Spring Festival in 1981. (Staten Island Advance)

But once restrictive laws preventing African-Americans from freely leaving and entering the state of Maryland were enacted, the oystermen brought their families to Harrisville. “It was generally difficult for newly freed people to earn enough money to purchase land, or to find individuals willing to sell it to them if they could afford it,” stated the LPC.

Recently, Sandy Ground history has been added to the Department of Education’s social studies curriculum, and a new Staten Island Ferry was named after the community. In addition, when the city named PS 62, it recognized that the school was built on historic soil by dubbing it “The Kathleen Grimm School for Leadership and Sustainability at Sandy Ground.”

A new Staten Island ferry boat honoring Sandy Ground was commissioned on Feb. 25. Mayor Eric Adams joined other city officials and members of the Sandy Ground Historical Society to unveil the Sandy Ground name. (Staten Island Advance/Jan Somma-Hammel)

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD CONNECTION

Sandy Ground is also believed to have played a vital role in the Underground Railroad.

There is documentation that Blazing Star Ferry Capt. John Jackson bought eight acres of land on Staten Island with another man from New York City named Thomas Jackson.

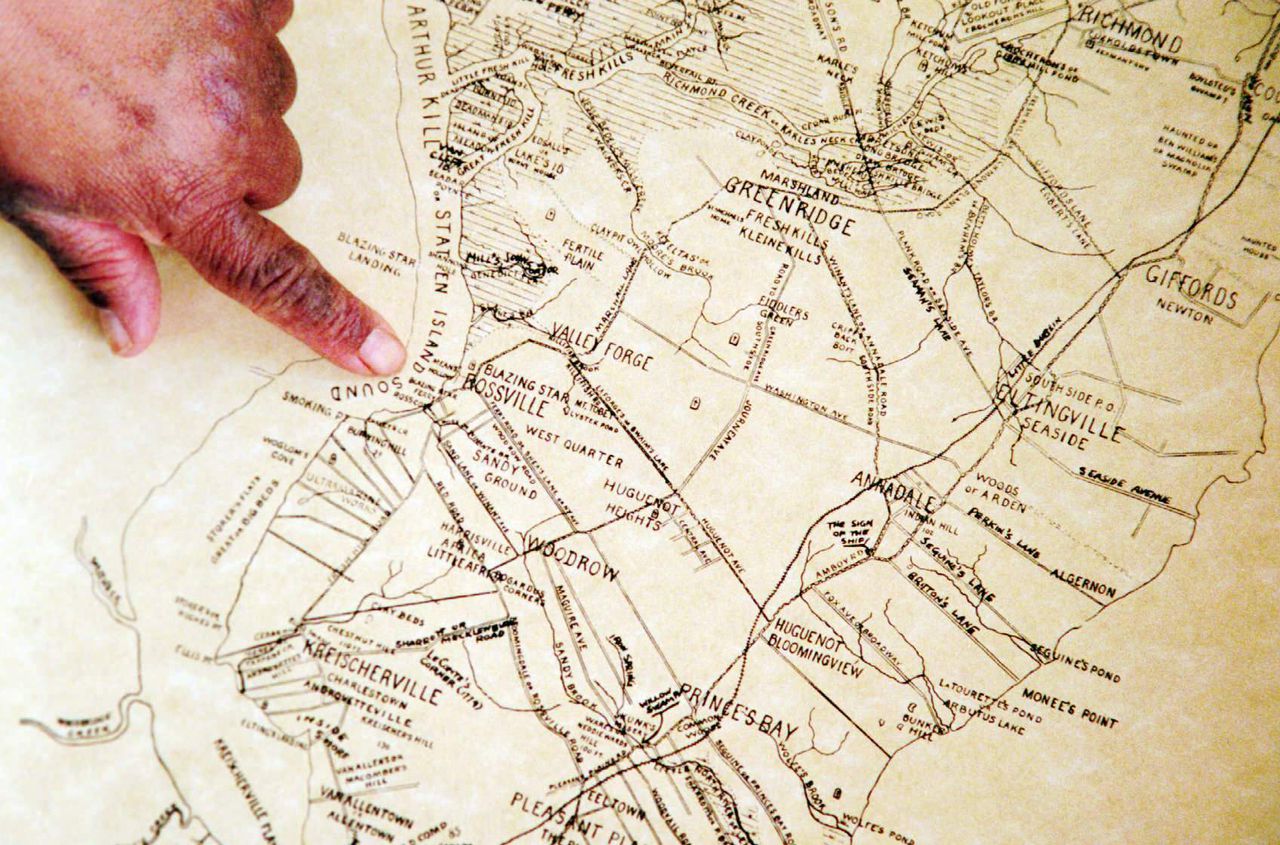

Julie Moody Lewis points to the spot where Capt. John Jackson ran the Blazing Star Ferry in the 1800s — believed to be one of the vehicles that transported people on the Staten Island link of the Underground Railroad. (Frank Johns/Staten Island Advance)Staff-Shot

The land is believed to be that which housed the dock for his Blazing Star Ferry, which was first called the Lewis Columbia. It has been written that Jackson — believed to be the first Black boat captain on Staten Island — transported “people and goods” on his ferryboat, between New Jersey and New York.

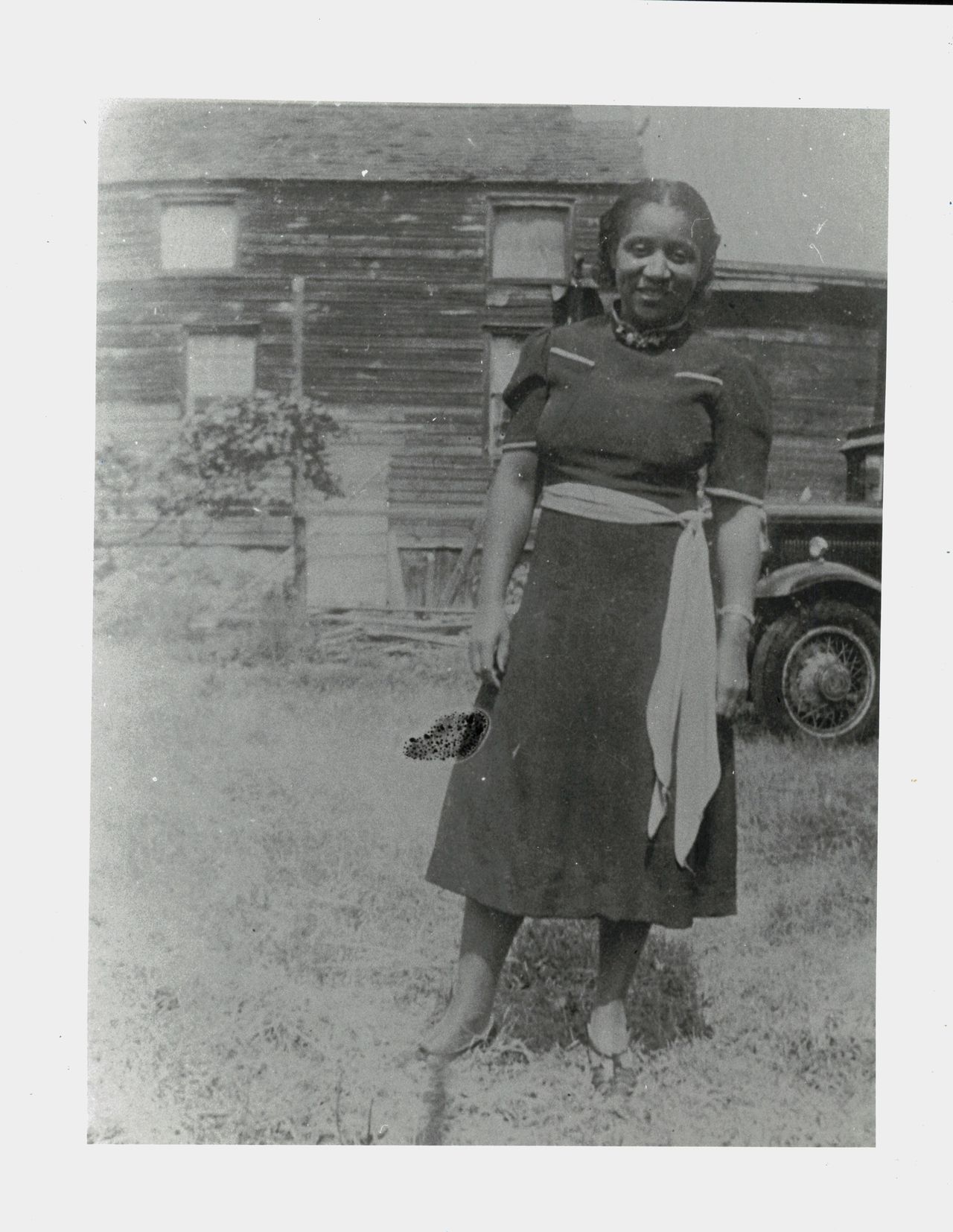

In the 1800s, Sandy Ground served as a refuge to Black oystermen who migrated from Maryland to flee the restrictive segregation laws that were imposed upon the oyster trade there. Here, a picture of Sandy Ground from 1932. (Staten Island Institute of Arts & Sciences)Staten Island Institute of Arts

Many believe that Jackson’s ferry was a vital part of the freedom trail between the two states.

“People knew Sandy Ground was a safe place,” said Moody Lewis. “Many Africans feared being sold back into slavery, because you couldn’t tell who had been enslaved and who was free. … We don’t have it written anywhere that it was officially part of the Underground Railroad, but what we do know is that Black men would come up from the South to educate the men at night and the children during the day. They taught those men how to read and write, and if they wanted to stay, they could make a life for themselves here.”

The house that once stood on this site on Claypit Road in Pleasant Plains was swallowed by the 1963 brush fire, but the steps and foundation remain — a playground for neighborhood children. They are: from left: Robert McKinney, Katherine McKinney, Jeffrey Moody, and Bernard McKinney (Staten Island Advance)Staten Island Advance

NOT THE FIRST CHALLENGE FOR SANDY GROUND

This isn’t the first time Sandy Ground has faced challenging times.

The 1880s and 1890s were said to be the “Golden Age” of the community, but polluted waters surrounding the borough put an end to the once-abundant oyster beds, which were officially closed in 1916, according to the LPC.

Built before 1859, the the Rev. Isaac Coleman and Rebecca Gray Coleman home at 1482 Woodrow Rd. in Staten Island, N.Y. is a vernacular frame structure that was granted landmark status by the city in 2011. (Photo courtesy Sandy Ground).

The Rev. Isaac Coleman and Rebecca Gray Coleman home at 1482 Woodrow Rd. as it stands today. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

“The community of Sandy Ground, so dependent on this industry, gradually declined. Some residents were able to find work in local factories, or commuted to Manhattan or New Jersey for jobs. Others relied on small farms to feed their families and supply markets in Manhattan. Eventually, however, this stable community of free and prosperous African-American families declined,” said LPC.

The next blow came when fires in 1930 and in 1963 destroyed many houses and much property throughout Sandy Ground.

A sign welcoming people to Sandy Ground is weathered and barely legible. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

The “Great Fire” of 1963, which extinguished dozens of homes across the South Shore of Staten Island, also stole those of at least 15 families in Sandy Ground, said Moody Lewis, noting her family’s home was destroyed.

Over the years, numerous acts of vandalism and a housing development siege during the 1990s led to more of community’s disappearance. But while many residents have moved away, the history has managed to stay alive.

Cacia Watkins, 44, of Staten Island, N.Y. whose grandmother still lives in Sandy Ground and is a descendant of original settlers, said she remembers coming to the community as a youngster and learning about its history.

Julie Moody Lewis, president of the Sandy Ground Historical Society, and descendant Cacia Watkins walk through Sandy Ground on Tuesday, Jan. 31, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

“At the end of the day, our later generations are not going to know about their history if Sandy Ground isn’t preserved,” said Watkins.

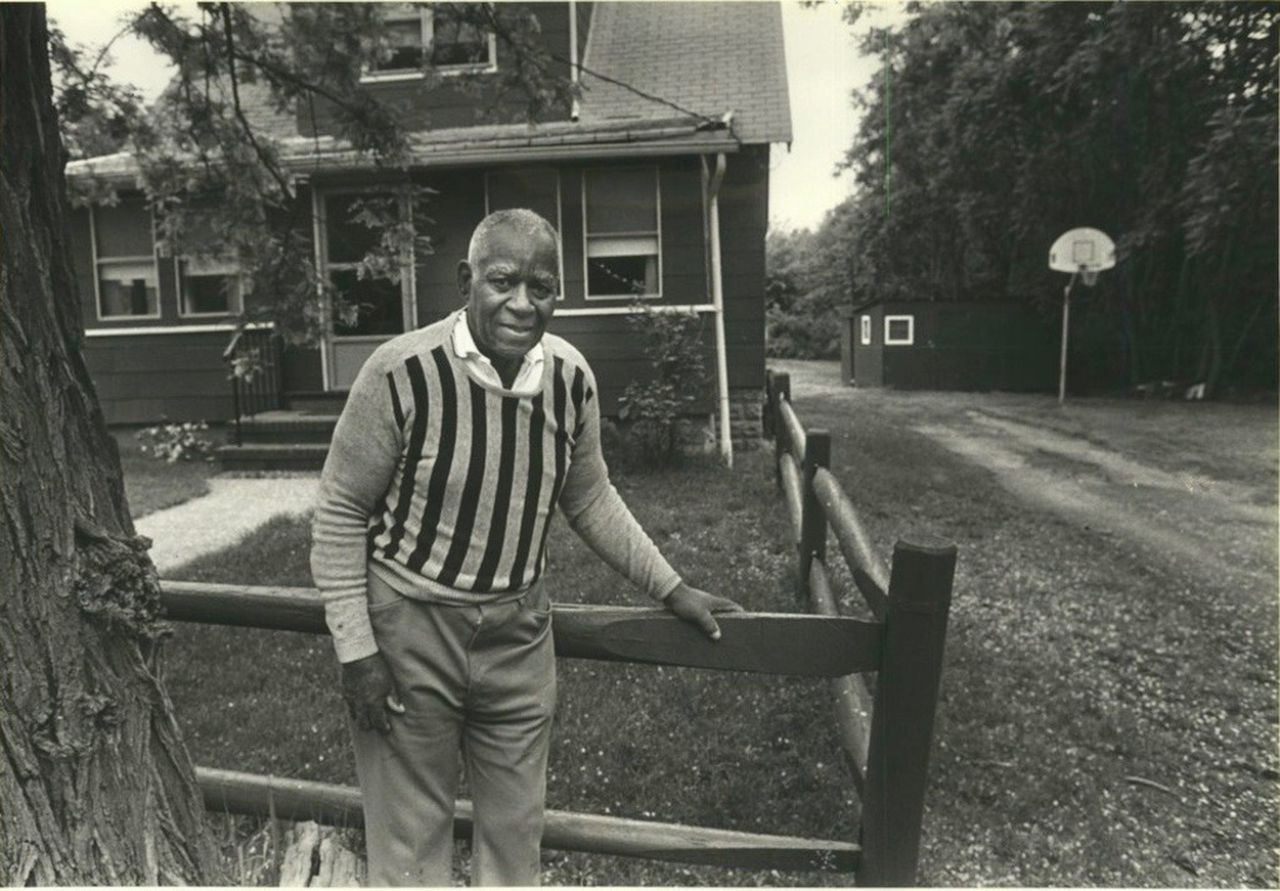

Harold Moody, a former resident of Sandy Ground who was Julie Moody Lewis’ late uncle, stands in front his home in Sandy Ground. (Staten Island Advance)Staten Island Advance

Paul Hansen, a neighbor who owns land that abuts the museum property, said he comes over and maintains the lawn, because he wants to help.

“If we can’t save this, then the history will be gone,” he said.

If you are interested in getting involved with the rebuilding of Sandy Ground, email [email protected].

A woman pictured in 1932 outside her home in Sandy Ground. (Courtesy Staten Island Institute of Arts & Sciences)Staten Island Institute of Arts

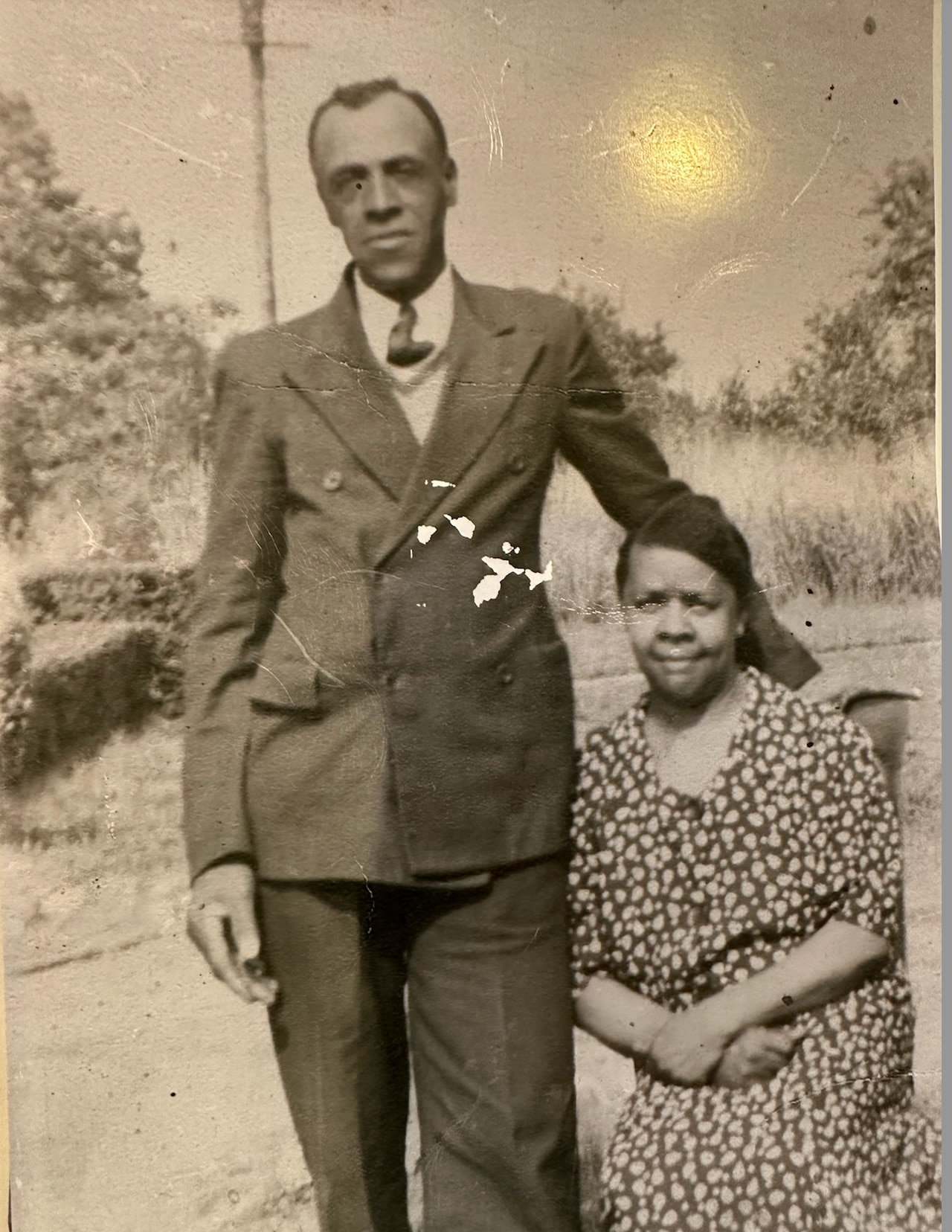

William and Jane Pedro in Sandy Ground. (Courtesy of Julie Moody Lewis)

MORE ON SANDY GROUND:

We’re losing an American treasure, right here on Staten Island | From the editor

Sandy Ground listed as ‘at-risk’: Working to ensure a treasured piece of NYC history lives on

More than 500 unmarked graves found in community settled by freed slaves