Who are the people buried on the Birmingham Zoo grounds?

Liza Montgomery was just 19 when she died of tuberculosis in 1888. Born just four years after the end of the Civil War, the young Black woman is buried on the grounds of what is now the Birmingham Zoo.

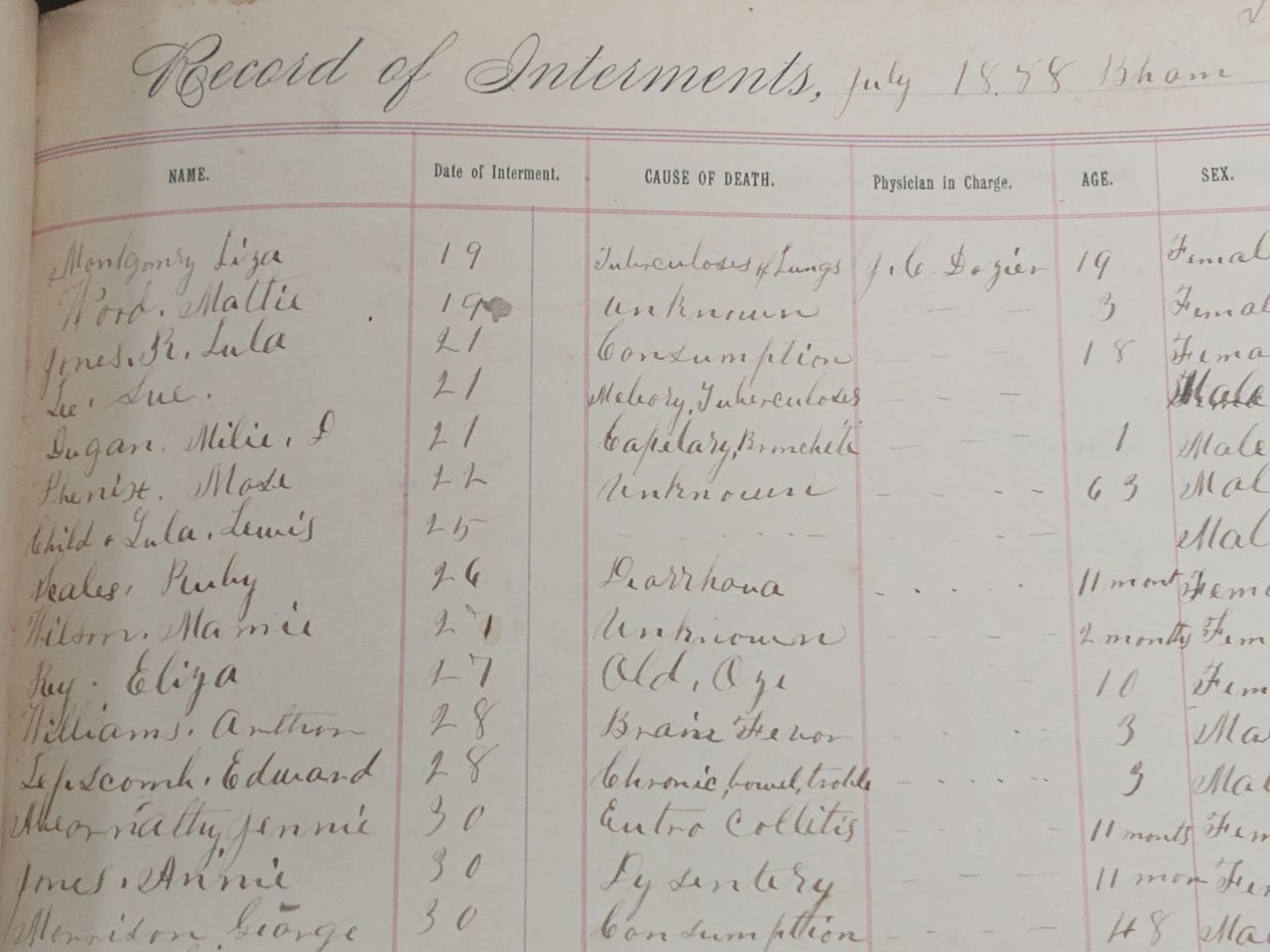

Montgomery’s name is the first written in a ledger of burials in Red Mountain Cemetery, the burial ground for some of Birmingham’s earliest and poorest residents.

As the zoo expands to add a new cougar exhibit, officials plan to hire an archaeologist to dig up and relocate about a dozen graves from the old cemetery.

Nearly 120 years since the last known burial, the expansion project highlights the old cemetery as modernity brushes against the quiet, wooded, and primarily forgotten burial ground of more than 4,700 people.

Wilson Fallin, professor emeritus of history at the University of Montevallo, said he is not surprised that memories of people interred at the cemetery are overlooked by history. Even in death, the poor and marginalized are historically overlooked in favor of “progress,” he said.

“Those who win take advantage of the land and are the ones who are able to use the power they have to get things done,” said Fallin, whose areas of study include African American history and the history of the U.S. South. “And those who are poor are the ones who get taken advantage of. That’s a fact of history.”

Today, the land formerly known as Red Mountain and Southside Cemetery, houses both the zoo and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens.

It’s nearly impossible to know who is buried in the 12 to 15 graves that will be relocated to make way for the new zoo exhibit. Many buried there are unnamed in the old ledger of burials and were laid to rest in unmarked graves. The names, handwritten in cursive on browned century-old paper, are often hard to decipher, yet the young ages of many of them continue to stand out on the pages.

Montgomery was buried there on July 19, 1888. The same day, another girl, Mattie Wood was also laid to rest. Mattie was just 3 years old. Her cause of death is listed as unknown.

The ledger, housed at Birmingham’s Linn Henley Research Library, lists the names, ages, races, causes of death, and sometimes the supervising physician in charge of the interment.

The names of Montgomery and Wood are preserved in the written records, yet many more entries are entered as “unknown,” people buried in the “potter’s field” at what was then on the edge of the young city in the area later known as Lane Park.

“With the majority of this, nobody knows who is where,” said Chris Pfefferkorn, president and CEO of the Birmingham Zoo. “But we still want to treat the people with the respect they deserve in this process. What we would like to do is not only add the marker, but we would like to add graphics and interpretative information about the history of Lane Park and the zoo because there’s a lot of history.”

Pfefferkorn noted the variety of people interred in the site, each with their own life experiences during Birmingham’s earliest days.

“We would be adding to what’s there, not taking away,” he said.

But officials must obtain a permit from the Alabama Historical Commission after presenting a plan to address graves on the zoo property.

“We contracted an archeologist to do a survey of the site because we know there are people interred all throughout Lane Park, the gardens, the zoo all over,” Pfefferkorn said.

The cemetery’s presence on the grounds of the zoo is well documented. According to a 1964 article in the Birmingham Post Herald newspaper, workers creating a rose garden at the nearby Botanical Gardens uncovered at least three graves.

Birmingham’s old cemetery contains the remains of diverse groups of people, Black and white, who largely shared a common link — being poor. Fallin said the lack of reverence for the lives and histories of the poor, particularly the Black poor, is not reserved for the South. For example, he recalled a visit to New York City about a decade ago, where a 10-story building was constructed over the graves of Black people.

Nevertheless, Fallin called it a positive step for progress that the current zoo leadership is taking steps to right a wrong committed decades earlier by showing respect for the people interred on the property.

“Those who are trying to preserve the bodies and location and all of that are certainly more enlightened than they were years ago,” he said. “That’s just a fact about Birmingham. This may be a step forward.”