UNAâs first Black student Wendell Gunn started class 60 years ago today

This story is part of AL.com’s “Season of Change: 1963” series. See more coverage here.

What’s remembered as Alabama’s most successful college integration occurred 60 years ago on Sept. 11, 1963, when Wendell Wilkie Gunn attended his first day of classes at Florence State College, now known as the University of North Alabama.

Gunn was initially denied entry from Florence State College on July 31, 1963, based on his race. Two months later, a judge ordered the school to consider his application.

That September, Gunn became one of few African Americans at the time to successfully enroll at a white public university in Alabama. His actions, historians and attorneys have said, would later pave the way for public colleges across the state to desegregate.

“I discovered years later that there were two colleges in Alabama, 200 miles apart, that were the only public ones that Blacks could attend,” Gunn said in a recent interview with AL.com. “And there were 11 schools where whites could attend and they were such that almost always students could go and not have to pay for travel and boarding and so forth.”

“It took about four more years for the rest of the colleges to be desegregated, but until that time, there were Black people all over the state who couldn’t go to college because they couldn’t travel.”

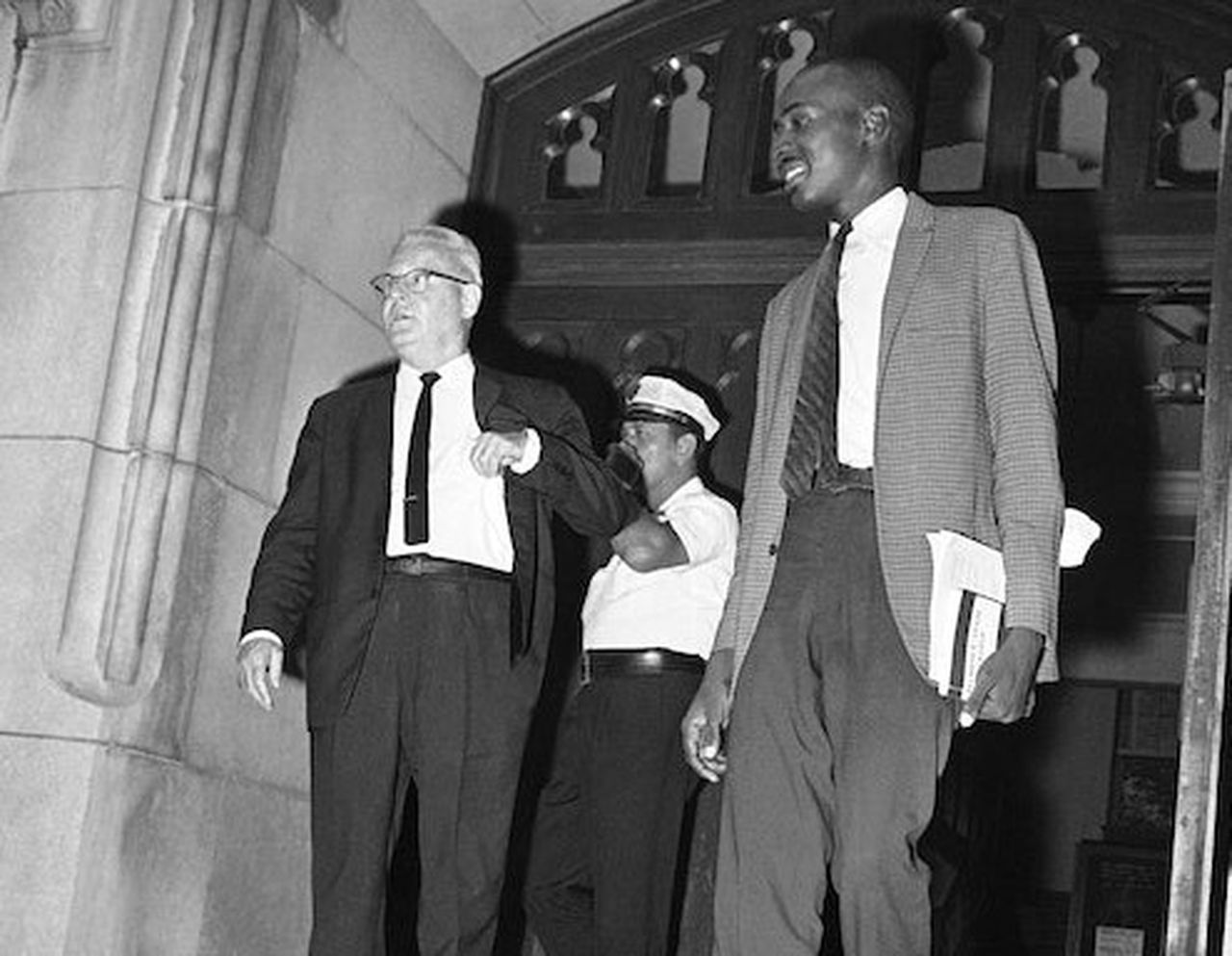

On Monday, the school commemorated 60 years since its desegregation in a ceremony on campus. Gunn, now 80, and officials recreated an iconic photograph taken near Cramer Way, where Gunn left his first day of classes in 1963.

“The admission of Dr. Wendell Gunn to the University of North Alabama and the desegregation of the institution laid the foundation for the admittance of hundreds of UNA alumni and students who not only add to the diverse fabric of campus but also to the local, state and national landscape,” Minette Ellis, the university’s chief diversity officer, said in a news release last week.

Wendell Gunn’s early life

Gunn grew up in Spring Valley, a rural part of Tuscumbia, and attended the segregated Trenholm High School through ninth grade.

“I was always at the top of my class, but I still wondered what was going on on the other side of the track,” he said. “But not enough to want to go there.”

Gunn was a shy kid but was talkative in class, and joined a rock and roll band in high school – much to the chagrin of his mother, who wanted him to become a preacher, he joked. He later transferred to Nashville Christian Institute, a predominantly Black private religious boarding school, for the final three years of high school.

In Nashville in the late 1950s, Gunn had heard about local sit-in demonstrations put on by students at Fisk and Tennessee State University, two historically Black colleges.

At the time, Gunn was the president of the student council at the private school, which was located in between the two universities. But the president of the school, who was white, had warned him not to get involved, Gunn said.

“They’re protesting for things that are important to us, and if they end up needing our help, I can’t say that I will not join them,” Gunn recalled saying to him.

After his high school graduation, Gunn followed his brother to Tennessee State, where he studied French and Spanish for a couple of years before changing his major to chemistry.

Things changed on a visit back home during his junior year.

A trip to the President’s office

Gunn was visiting a friend, Jeanette Lambert, who was married to one of Gunn’s high school classmates, when he saw a Florence State College yearbook on their table.

He realized he’d lived in the Florence area all his life, but had never seen the school’s campus.

So he went to check it out for himself.

“I thought it was going to be OK when I went over there, because I didn’t have any negative things to happen to me in my life,” he said. “I felt like I got along with my neighbors both on my side of the track and the others.”

Gunn was directed to the president’s office, where the dean, Turner Allen, looked at Gunn and asked him, “Who sent you here?”

“I said, ‘Nobody, I live across the river,’” Gunn said, explaining to the dean that he simply needed to complete his junior year of classes.

Then the president, E.B. Norton, chimed in, Gunn recalled, and said, “Well I’m sure you understand that we have no authority to admit a Negro.”

“I was ready to back out of the room then, but he kept talking,” Gunn said.

Norton told Gunn that if he were to sue in federal court, the college would have no choice but to admit him. After attempting to persuade Gunn to apply to one of the two state HBCUs, Norton gave Gunn a Florence State application and advised him not to tell anyone but his parents if he planned to apply.

“He was not negative at all, he was just telling me the way it is,” Gunn said.

‘I’ve got to go somewhere’

At the time, most public colleges in Alabama were still segregated. Just a few months prior, in June, Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood courageously defied Gov. George Wallace’s infamous Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, becoming the first to successfully desegregate the University of Alabama.

Fred Gray, the attorney who sued on behalf of Jones and Hood, was also a graduate of the Nashville Christian school that Gunn attended.

When Gunn came home that afternoon with the application in hand, his mother didn’t ask a single question. Instead, she picked up the phone and called Gray.

“She handed me the phone and then he said, ‘Do you want to go?’” he recalled. Gunn tried to back out, he said, telling the attorney that his family couldn’t afford a lawsuit.

“I didn’t ask you that,” Gunn recalled Gray telling him. “I asked you if you want to go.”

“Finally, I said, ‘Well I’ve got to go somewhere.’”

Under Gray’s advice, Gunn filled out the application and placed it and a check on the president’s desk.

Soon after, the telephone started ringing. White people who Gunn didn’t know wished him dead. Others claimed their rights were being taken away.

A few days later, Gunn received a letter from the president denying his entry, noting that “Neither the Alabama Legislature nor the State Board of Education has authorized the college to accept Negroes.” UNA officials later admitted that Gunn had a “very good academic record.”

In Gray’s autobiography, the civil rights attorney called Gunn’s case the easiest he ever argued, due to the way Norton wrote the letter.

“They made it clear that my race was the reason that they couldn’t admit me,” Gunn said.

After a remarkably short court proceeding, a judge praised Norton for his candor and ordered him not to view Gunn’s application any differently from another applicant.

“I think that Dr. Norton had figured the time was right and he didn’t want to happen on this campus what had happened somewhere else,” Gunn said. “But he didn’t have an applicant, and I walked in and he had an applicant.”

‘I learned to love the school’

Gunn finally registered for classes on Sept. 11 of that year.

The threatening phone calls had stopped, Gunn said, but officials were nervous for his safety.

A cab company offered to drive him to and pick him up from school every day. For the first week, Dean Allen escorted Gunn to class – an offer that Gunn felt made him look too “conspicuous,” and he urged the dean that he could handle himself on his own.

Gunn took science classes and joined the choir. He performed Ray Charles and country western music at the spring concert. Two months into the fall semester, Gunn sang “Wonder While I Wander” with George Wallace in the audience.

But for a while at Florence State, white students didn’t talk to Gunn, and he didn’t speak to them. He didn’t go on campus at night and he avoided athletics events.

That changed on awards day, when he received the school’s Physics Achievement Award. Gunn was shocked to win the prize and became emotional, and the whole room stood up and cheered for “what had to be four or five minutes,” Gunn recalled.

“When I talk about that now it really, I get so emotional,” Gunn said. “And maybe what it was was the tension. I didn’t realize how much tension I had been suppressing during those first few months. And then it just poured out.”

Gunn graduated from Florence State in 1965 and went on to work for the White House during the Reagan Administration.

He’s now on the board of trustees at The University of North Alabama, a campus that he said has grown more diverse.

Today, 12% of UNA students are Black, 5% are Hispanic and 70% are white, according to state data. The university renamed the school’s student center after Gunn in 2018.

“Florence State made more progress in the one year that I was there than anybody will admit,” he said, noting that officials kept in touch with him throughout his career.

“I learned to love the school,” he added. “What can I do but love my alma mater? Because it acted like it loved me.”