‘Thrilling discovery’ in library vault shared by ‘Africatown’ author

Callousness, capriciousness and merciless time have caused pieces of the Africatown story to be lost. Diligence, devotion and unexpected luck have saved others. Interested onlookers got a rare sense of all those forces colliding as author Nick Tabor visited Mobile this week with his new book in hand.

Tuesday night at the GulfQuest Maritime Museum, Tabor read from, discussed and signed copies of “AFRICATOWN: America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created.” It’s an eye-opening book that fleshes out the narrative of the Clotilda’s last voyage with historical context. It goes on to illustrate that Africatown didn’t exist in a bubble for 150 years after its founding, giving a much fuller sense of the challenges the community faced in various eras of its timeline.

RELATED: Newest book on Clotilda and Africatown adds context, fills in gaps

Before he spoke, Elizabeth Theris-Boone, manager of the Mobile Public Library’s Local History & Genealogy Library, spent a few minutes in front of the capacity crowd in GulfQuest’s theater. She reviewed the considerable resources that the library makes available to the public – including one rediscovered just in time to play a significant role in Tabor’s book.

Nick Tabor signs copies of his book “AFRICATOWN: America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created” during an appearance March 28, 2023, at Mobile’s GulfQuest Museum.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

“This is another oral history project,” she said, describing a box of old tapes. “It was conducted in by the library in the ‘70s. I found it in the vault one day. 159 reel-to-reels that we had no way to play or listen to.” She sent them off to be digitized.

A few minutes later, Tabor described a “Eureka” moment.

“I had some thrilling moments, thrilling discoveries,” he said. At one point in the middle of the COVID-19 lockdowns, he said, he was re-reading an old Press-Register article about Clara Eva Allen Jones, known as “Mama Eva,” a second-generation Africatown descendant who lived into the early ‘90s.

He was reading it “for like the 100th time,” he said, when something new caught his eye. “It had all this information on her life, but I noticed that it said somewhere, almost like a footnote, that this came from an interview that was done by the library,” he said. He emailed Theris-Boone, asking “Does this still exist, by any chance?”

Her reply: “Well you’re in luck, it was in the vault … it was on reel-to-reel but it just got digitized.”

Elizabeth Theris-Boone, manager of the Mobile Public Library’s Local History & Genealogy Library, stands in the library’s vault.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

Luck was a big part of it, starting with the good fortune of Mama Eva’s extraordinary lifespan. She was a daughter of Pollee Allen, a Clotilda survivor who married more than once and continued having children at least into his 50s. She was born in 1894 and lived to 1992, more than long enough to be selected for a 1970s oral history project.

But the story of the tapes wasn’t all luck. Partly it was a matter of the Mobile Public Library doing what libraries do: Preserving knowledge, preserving culture.

Theris-Boone said two library workers apparently launched the project “at a time when I think … oral history fever was gripping the nation.” The collection has its quirks: “the scope was not very focused,” she said. Most of it was interviews with people of note in the Mobile area. Some capture the ambient sounds of events such as Mardi Gras parades and the 1978 Greater Gulf State Fair. Others are recordings of public meetings, broadcasts and religious services, even concert or two.

“Some people felt like it shouldn’t have been done by the library. Like, our job would be more to preserve and gather information,” Theris-Boone said. “The main critique was they didn’t think the library should be trying to create history. But somebody has to do it. Years later, it’s proven to be a great resource.”

“They do have their weaknesses,” Theris-Boone said. “It’s still a wealth of information.”

The original tapes still sit secure in a climate-controlled vault, among shelves of other interesting material. The digital audio files haven’t been transcribed, but librarians have a list of who’s on which tape, and a box of index cards with some description of the recordings’ subject matter.

The vault at Mobile’s Local History & Genealogy Library includes a wide range of artifacts, and isn’t limited to print formats.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

As for the coincidence they happened to become available on digital format just about the time Tabor was living in Mobile, researching his book, that’s the kind of thing that makes a hunter feel like they’re on the right trail.

“There were some names that jumped out to me that probably would not have jumped out to most people,” he said. One example: Thelma Shamburger, a midwife who served the Africatown community.

“The Mama Eva one was the most valuable,” he said. “There are parts of that tape that are stuck in my mind.”

Think about it: The person who spoke into that recorder in the late 1970s was born to someone carried across the Atlantic by the Clotilda in 1860. To her, survivors such as Cudjo “Kazoola” Lewis were living people. Her memories are virtually a living connection to them.

“She talks about her father’s cooking methods, the way he would make food at home,” Tabor said. People often ask him why African language didn’t endure in Africatown, the way the Gullah language did in some East Coast enclaves. “She sort of speaks to how it is that that did not happen,” he said. “There was a lot of stigma for kids in her generation.”

It’s not just information. It’s emotion.

“I can just hear her voice,” said Tabor. “She says that her father and Cudjo, she remembers them sitting down sometimes and crying together.”

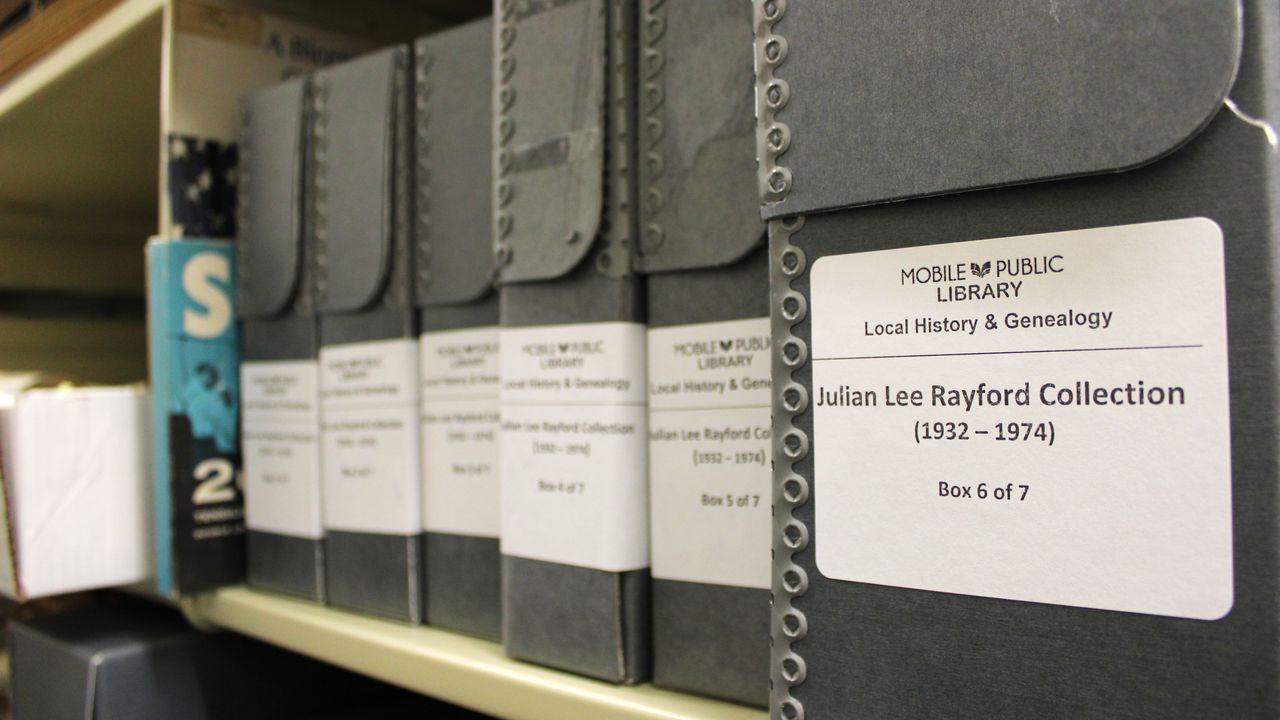

Mobile historian Julian Rayford is well represented in the vault at Mobile’s Local History & Genealogy Library.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

At GulfQuest, Tabor began his presentation with a reading about Prichard Mayor John Smith’s efforts to obtain federal recognition of Africatown as a historically significant area in the early ‘80s. Despite support from Sen. Howell Heflin, the effort failed – and a few years later, the widening of Bayfront Road obliterated houses that quite likely had been built in part by Clotilda survivors. (Smithsonian Magazine has published an excerpt on Smith’s efforts from Tabor’s book.)

Amid such losses, the fact that the recording of Mama Eva was made, preserved, and rediscovered in a timely manner is a welcome win, and not just for Tabor.

For New Yorker Tabor, his recent swing through town – signing books at GulfQuest, the library and Page & Palette – was a chance to revisit a city he called home during his research.

“I really did enjoy my time here,” he said. “It’s a beautiful town.”

“I’ve been pleased to see that there so much interest, such a hunger here to learn more about this part of the city’s history,” Tabor said. Like the makers of the documentary “Descendant,” he said, he’d wondered about the reception.

“I assume there are people in Mobile who don’t care for it, maybe they didn’t watch it, and I’m sure that’s true of the book,” he said. “I think there are probably people who wouldn’t care for it if they did read it. But there is a large audience for this kind of thing.”

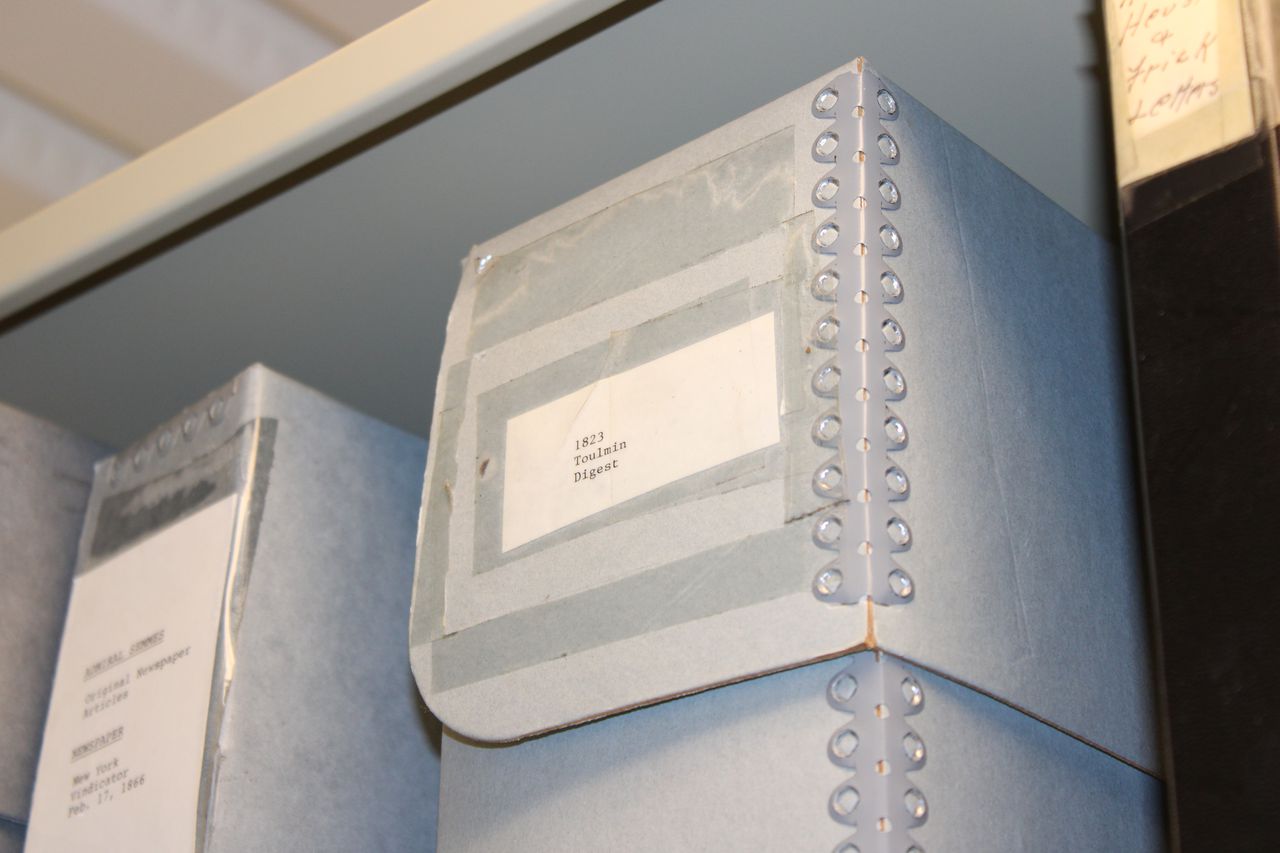

Among the items in the vault at Mobile’s Local History & Genealogy Library: Toulmin’s Digest, a compilation of the laws of the state as of 1823.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

And if those people want to do some digging on their own, the library is ready to help. As interest in the topic has grown over the last few years, a “Clotilda Collection” has been added to Mobile Public Library digital collections available for online viewing.

Those digitized reel-to-reel recordings, a whole slice of life from the ‘70s, are available too.

“We don’t have a problem with sharing,” said Theris-Boone. “We will email people the files. Access is our mission.”

The Local History & Genealogy Museum is at 753 Government Street, near the Ben May Main Library. It’s open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Saturday. For information call 251-494-2190 or email [email protected].