The rise of the abortion cowboy

The doctor wants a pair of boots. Not just any boots, either. A specific brand of cowboy boot, handcrafted in Texas. Boots that adorn the feet of the

Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, for instance, and singer-songwriter Chris Stapleton.

We’re at the airport in El Paso, after a seven-hour journey from a small regional airport in the Southeast to a major metropolitan airport to, finally, this airport, about an hour from the abortion clinic in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where Dr. Aaron Campbell will work for a couple of days before flying back home. Campbell, who asked that his precise travel route not be published for safety reasons, has made this journey 10 times in the last year. But today, before he starts his rotation, he’s got plans. He wants proper cowboy boots and a cowboy hat to complete the look.

You cannot begrudge the man this indulgence. Campbell is a mild-faced doctor from Knoxville, Tennessee, who only finished medical school about a year before the fall of Roe v. Wade. But for most of his adult life, he’s known that he wanted to go into this line of work—it’s what his father, Dr. Morris Campbell, did, too. The elder Campbell had graduated from medical school in 1973, the year that Roe became law of the land, so he had witnessed what life was like before his patients had access to safe and legal abortions. He was determined to help women who did not want to be pregnant. Aaron was still in college when his father passed away suddenly in 2012. By the time he finished his medical school residency at the University of Pittsburgh, his father’s clinic was being run by someone else, who was ready to retire. If Campbell didn’t step up, it wasn’t clear anyone would. In June 2021, he moved back home and took over.

The next summer, all hell broke loose.

In the months following the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, as abortion ban after abortion ban went into effect across the country, including in Tennessee, physicians who’d once had thriving abortion practices were forced to shutter their clinics and decide what to do next. Dr. Campbell was faced with a choice: Stay in Tennessee and give up providing abortion care (not an option for him), move to a state with liberal abortion laws (away from his partner), or remain in Tennessee and become a traveling abortion provider.

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: Director Shannon Brewer (right) speaks with Dr. Aaron Campbell at the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

He chose the latter. So did many others. Dr. Campbell is among a growing cadre of doctors who regularly cross state lines to provide this essential, and increasingly vanishing, service. Melissa Fowler, chief program officer at the National Abortion Federation, a professional association of abortion workers, estimates that between 100 and 200 of the physicians affiliated with NAF travel for their work, a significant jump from pre-Dobbs numbers; other clinic staff, like nurses and front desk assistants, are also commuting between states. The people keeping abortion services afloat juggle complex itineraries, sometimes working at multiple clinics across several states, all in the name of shoring up access in any legal way possible.

I first wrote about Dr. Campbell back when Roe was still law of the land. So when he described just how much his work had changed, I wanted to know if there was any chance he would let me tag along on one of his trips. He agreed, and I hoped that in traveling with him, I might have a window into one abortion provider’s new normal. Much of Campbell’s life over the last 15 months has been spent in cars and on planes, traveling across the country to provide care to patients, many of whom are also traveling great distances. If he’s not en route to a clinic, he’s working at one, or he’s on his way back home for a brief respite before heading out again.

His new lifestyle hasn’t left him much time for fun, and, as the adage goes, one can’t pour from an empty cup. “I’m missing out on living my life,” he says ruefully.

So today, there will be a little bit of fun.

The boots are a top priority. Dr. Campbell has done his research, and his heart is set on a pair from Lucchese’s nearby factory outlet. He tries on a brown leather pair with intricate stitching, then one with a classic pattern stitched into the black shaft of the boot. The foot is constructed of ridged caiman crocodile skin in a deep oxblood color. He decides to seek another opinion and pulls out his phone to FaceTime his girlfriend. After several rounds of rhythmic beeping, she answers, and they banter a bit before he takes her through the options. She’s supportive of this fashion endeavor, but she has one caveat: “If you wear any of those boots with scrubs, I’ll disown you,” she jokes.

After more deliberating, he settles on the crocodile. “I’ll be like an abortion cowboy,” he warns, grinning.

The boots, of course, need an accompanying hat. After staggering around Starr Western Wear on our own, the doctor asks a salesperson to direct him to the hats. They’re in the back, stacked floor-to-ceiling in cubbies that seem to be built into the wall.

We start with the Stetsons. “Black, I think,” he muses. The real trick is going to be finding the right size. After he has tried on several, I do my best imitation of a hat rack and we’re still not sure of the correct fit. A young woman directs us to an island in the middle of the store staffed by what looks to be a teenage boy with friendly eyes and deep cratered acne around his mouth. A time-speckled photo of John Wayne hangs above his station that says, “Courage is being scared to death but saddling up anyway.”

Dr. Campbell remembers the day Roe fell very clearly: the emotion, the chaos, the back-and-forth with his clinic’s lawyers. Most vividly, perhaps, he remembers that it also marked the first time he was forced to turn someone away from his clinic, without being able to offer a real alternative.

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: Dr. Campbell organizes his medical tools prior to a procedure at the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

It was early in the afternoon, hours after the Dobbs decision. Following the advice from his lawyers, Campbell and his staff hurried to wrap up their work. They drew the blinds, locked the doors, and the staff gathered in the lobby to process their last day working together. From the back door came the sound of insistent knocking. Campbell peeked out between the closed blinds to make sure the sound was not coming from a euphoric protester. Instead, he says, he saw a frightened Jamaican man and woman, seasonal summertime workers from nearby Sevierville.

“They were begging us to see them,” he recalls. “I kept saying things like, ‘I want to help you, but I can’t,’ and they kept saying, ‘We will pay you anything, we’ll pay you whatever you want, you can come to our home.’” Eventually, he had to close the door, unable to respond to their pleas.

Dr. Campbell did not get into this profession to feel helpless. Even before the Dobbs decision, it was becoming clear that his work would likely be severely limited—if not banned outright. So in early 2022, he applied for medical licenses in a handful of states where abortion seemed to be in less imminent danger. By the end of June, he’d set up a contract at Little Rock Family Planning, in Arkansas, though his time there was cut to a single day before the Supreme Court ruling shuttered the clinic. By that summer, Campbell had gotten approval to work in Charlotte, Pittsburgh, and Las Cruces. He also began a regular rotation at the University of Tennessee’s Medical Center providing maternal care to people struggling with substance use disorders.

Abortion doctors have long traveled for work, particularly to provide care in states with strict abortion laws and hostile political environments. Some physicians are more comfortable living in areas where they know their occupation won’t faze their neighbors—especially if they’re raising children—so they get on planes and in cars to cross state lines on their way to the office. Their safety concerns are not unwarranted—abortion opponents have often used targeted harassment of abortion providers and staff as an intimidation tactic, in the hopes that abortion workers could be scared out of their jobs. In the year leading up to the fall of Roe, NAF reported a 20% increase in death threats and threats of harm to clinics. Reports of stalking, which applies to patients and providers, rose 229%.

While those factors are still very much in play, providers and other traveling clinic workers are also becoming more mobile as people needing abortions are increasingly funneled into a handful of states on the edges of vast new abortion deserts. In New Mexico, for example, the number of abortions shot up 220% between January 2020 and June 2023, according to data from the Guttmacher Institute, a think tank that researches access to reproductive health care. NAF has adjusted to this new landscape with the creation of a program that helps to match clinics with staff who are willing to travel or move altogether. “We’ve been doing this work since before Dobbs,” says Fowler. “But as you can imagine, there’s been a dramatic increase since the leak of the decision.”

All of that means a grueling travel schedule for physicians like Campbell. Over the last year, his weeks have often included full days of work on Tuesday and Wednesday at the UT Medical Center, followed by nighttime travel to one of three out-of-state abortion clinics, where he works through Saturday. Which clinic he visits and at what time varies depending on the fluctuating schedules of Campell, other traveling providers, and the needs of the clinics. He returns home on Sunday, scrambles to catch up on laundry, groceries, and errands on Monday, and starts all over again on Tuesday. He’s made it a point to schedule one weekend off per month, but acknowledges, “This has been at times excruciatingly exhausting.”

Recently, he found himself at a something’s-gotta-give crossroads, and so he put in his notice at UT—his most stable job, with a salary and benefits. “I don’t necessarily want to go,” he says. “But I can’t keep doing this job and my other work at the level that I’ve been doing it. But abortion work is the mission of my career. I don’t want to compromise on that.”

At the Western wear shop, steam hisses out of a curved metal apparatus that’s attached to the counter, and the young worker uses the wet heat and quick, expert strokes of a stiff-bristled brush to shape the hat into the “rodeo style” Campbell has selected. The doctor pays, and the hat is lowered into a gigantic box that nearly brushes the ground as Campbell holds the handle at his hip, like any other shopping bag.

He proudly carries it to the car, chattering about his newfound need for bootcut jeans, and we settle in for the hourlong drive across the state line to Las Cruces.

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: Rosa Ulibarri, an operating room technician, listens to Dr. Aaron Campbell as they prepare for another patient at the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

When the doctor pulls into the parking lot of Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization the next morning, there are no protesters blocking the way. New Mexico, a state with a Democratic governor who has been unabashed in her support for abortion rights, is like another planet compared to Jackson, Mississippi, where Women’s Health Organization was originally located. For 15 years, the clinic, dubbed the Pink House for its Barbie-pink facade, was the only one in the state. It was also the plaintiff in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that first sought to challenge Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban and ultimately overturned 50 years of federal abortion protections.

When it seemed clear that the clinic would not survive the new conservative majority on the Supreme Court, Diane Derzis, the clinic’s owner, along with Shannon Brewer, the clinic’s director, decided it was time to get serious about a move. Brewer isn’t someone who hides, ever, but to have an identity that is so tied to abortion in a state where lawmakers have dedicated themselves to outlawing her work is no small thing. There would be no relief from that. And she wasn’t about to give up. “We started looking in different places to see what was a good fit, where we could help the most women,” Brewer says. “New Mexico was always one of the places we had talked about.”

Leaving meant saying goodbye to the place where she’d spent her entire adult life, to the home in which she’d raised her six children. She misses her family, but one of her granddaughters just came to stay with her for three weeks, and she goes back to Jackson to visit, too. “Moving here was actually one of the best decisions I’ve made in a long time,” she tells me. Only one other staff member from the original Pink House joined her.

Pink House West is situated close to the western border of Texas, perhaps the single-largest abortion desert in the country. Back in 2021, Texas was one of the first states to pass a near-total ban on abortion; one study from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health found a 50% drop in abortions in the month after the law was passed. Other states were unprepared for the influx. “The overall availability of abortion care in neighboring states was limited,” the study’s authors wrote. “Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, combined, had fewer facilities

providing medication and procedural abortions, compared with Texas, and had approximately 40% of Texas’ annual abortion volume.” Brewer says some 95% of the Pink House West’s clientele are from across the state line.

Other providers also have found new homes in the southwest. Whole Woman’s Health, the clinic that was the plaintiff in the 2015 Supreme Court case about Texas’ abortion restrictions, opened a new location in Albuquerque in March. Planned Parenthood, too, opened a clinic in Las Cruces last spring and has reportedly expanded its services.

Derzis, Pink House West’s owner, mostly works remotely from her home in Alabama. She says that Las Cruces is by far the most supportive place she’s ever opened a clinic. Pink House West has been warmly welcomed by the community, and protesters know that there’s a line. “Even when they’re there, they don’t scream and act like fools, like we’ve come to expect,” Derzis notes. She would know—she’s owned seven clinics throughout her career. The first, in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed by anti-abortion terrorist Eric Rudolph in 1998, killing an off-duty police officer who had been working security and severely maiming a nurse. Currently, she owns four clinics: one in Georgia, two in Virginia, and one in Las Cruces.

When we walk into the clinic from the parking lot, Campbell is greeted warmly by the front desk staff, and we make our way through a long hall to Brewer’s office. He eagerly tells her about his new boots and hat, and she chuckles. They catch up a bit, and he shoos himself out of her office before she does. At the other end of the clinic is the office that Campbell shares with a rotating cast of four other doctors. Derzis, who didn’t want her nomadic doctors to have to furnish their offices, provided a bookcase, where each physician has a shelf, and an old glass-topped wooden desk.

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: Rosa Ulibarri, an operating room technician, conducts an ultrasound during a procedure at the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

Derzis bought a condo in Las Cruces for the physicians to have a safe place to stay. Once, Derzis tells me, a doctor who went to work at the Pink House in Jackson stayed in a hotel, and anti-abortion protesters showed up at her room. “After that, it was like, ‘You know what? We’ve got to have a place for them,’” she says. “So in most places, we do, and it makes sense to go in and buy the real estate because it’s part of the business.”

There are only a handful of patients today, a rarity, though two of them will need second-trimester procedures. A medical assistant named Rosa pokes her head into the office to announce that a patient—who is early in her pregnancy and seeking a medication abortion—is ready to be seen.

In a room painted a blinding marigold color, Campbell counsels the young woman, a New Mexico resident with a neon manicure, about how medication abortions work. She asks how the medication will affect her ability to go about her day, what she should eat, and whether the misoprostol pills, which may be taken vaginally, could fall out (that’s unlikely, Campbell assures her, the medication absorbs quickly). He warns that it could take up to 24 hours for the tissue to pass and that she should expect cramping and bleeding. He recommends ibuprofen for pain management. Campbell keeps his voice gentle, his language clear, his demeanor unassuming. There are no boots, no hat, no concerns about anything at all beyond the person in front of him.

He explains the symptoms of infection to her. “I tell patients from Texas that if they have to go to the hospital for excessive bleeding, to just tell the ER that you were pregnant and you think you’re having a miscarriage,” he says. “I know you live in New Mexico, but just so you know, if you go to Texas for some reason, say that. They cannot tell the difference between a miscarriage and medication abortion.” She nods. He tells her to take a pregnancy test in four weeks and to call the clinic immediately if it’s positive. Someone from the clinic will be in touch in a few weeks to check in, too.

“Cup your hand for me,” he instructs, and she reaches out toward him. He dispenses the mifepristone, the first medication, into her palm. A paper cup of water is nearby and she swallows the pills.

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: Pro-Life activists are seen through the window as they protest outside the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

Even as someone who is seeing the harm of abortion bans unfold firsthand, Campbell offers no pithy abortion rights slogans. “The abortion conversation is hard because it’s easy for each side to demonize the other,” he says when we are back in his office. “And it’s easy for me to say, as an abortion provider, that anti-abortion people don’t care about women, or don’t care about the bad outcomes.”

But he actually doesn’t believe that. “I think the reality is that everyone wants to do the right thing,” he says.

And yet, he admits he’s “lost his optimism for the movement,” which is how abortion rights advocates refer to their work. “I think in the past there was this attitude that if you work hard enough, and you fight hard enough, that it might not be easy, but things will be okay,” he says wearily. “I certainly don’t feel that anymore.”

He knows that his life’s work doesn’t have to be this hard. “I could move to a place where it’s easy to do this, like Boston or San Francisco, where they are saturated with abortion providers,” he says. “But my goal has been to increase access to safe abortion in areas where there’s a lack of access or where it’s hard to provide abortion or where there are no other providers, which is why I’m traveling.”

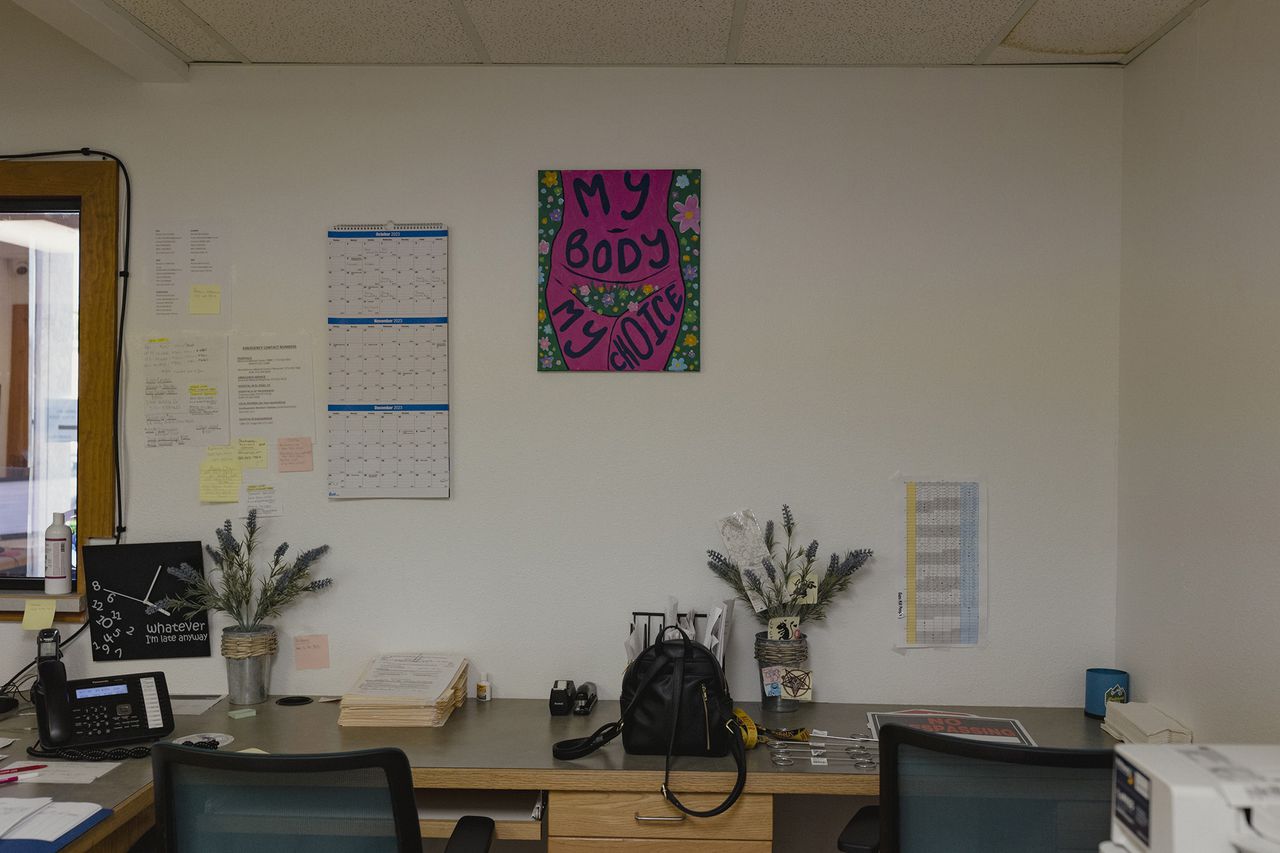

LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO – October 9, 2023: The interior of the Las Cruces Women’s Health Organization in Las Cruces, NM on October 9, 2023. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for Mother Jonesfor Mother Jones

He’s not ready to give up, but he knows it’s very likely the day will come when treating himself to cowboy boots won’t be enough to push him through the endless hours in airports and rental cars and cities that are not his own. He won’t let himself think too hard about it, yet he acknowledges that it could happen. “I don’t know,” he tells me, “that I’ll do this forever.”

After two days of work in Las Cruces, he sets his alarm for 2:30 a.m. That will give him enough time to prepare the condo for the next doctor, make the hourlong drive to El Paso, return his rental car, and make it through security. As usual, he has an upgrade to first class for this trip—his lifestyle means an abundance of miles with the airline he uses, and he’s become an expert in the inscrutable world of travel points and perks. With the latest Zelda game loaded up on his Nintendo Switch, he has something to distract him while he’s in the air. He won’t be checking his new hat—that, he will be carrying on with him.