The end of plastic may be near. But what happens to water crisis areas like Flint, MI that depend on it?

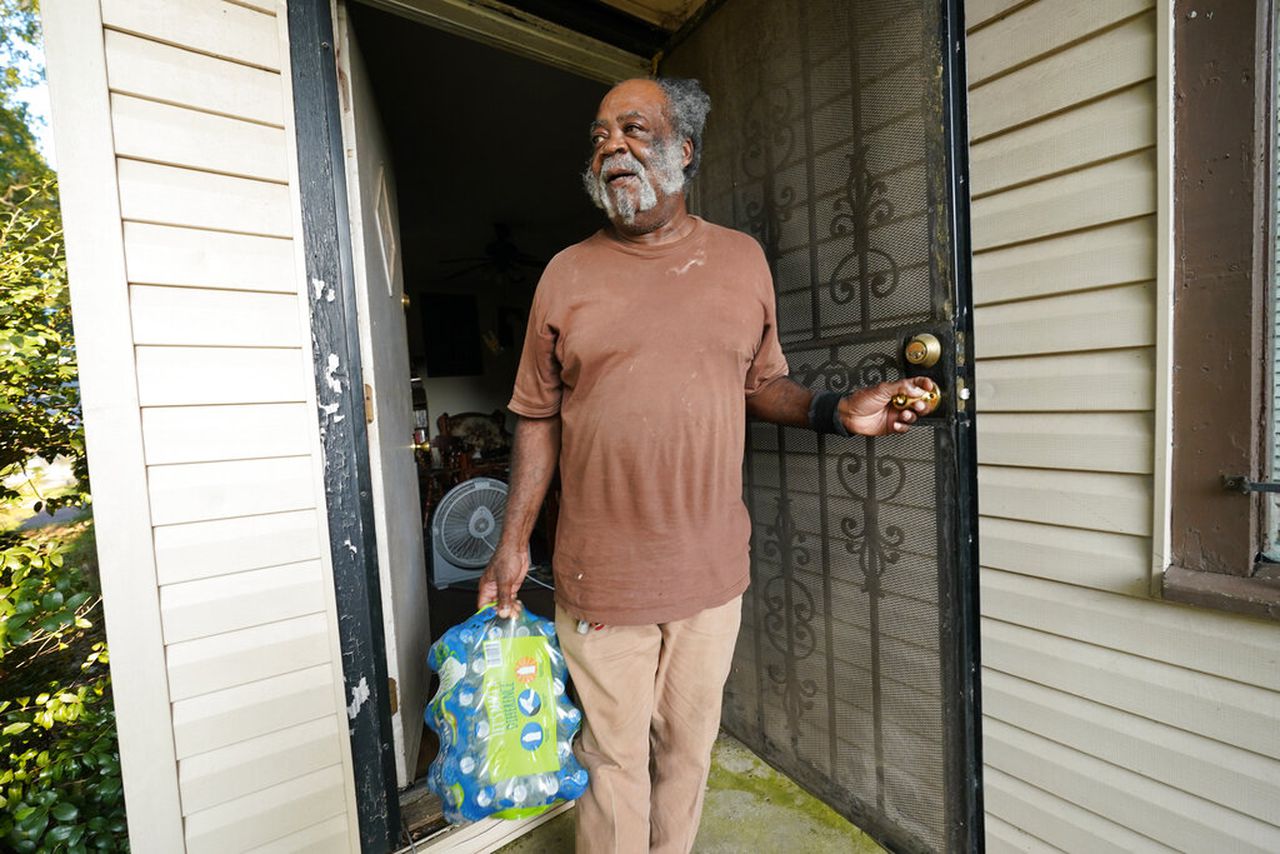

For at least the last 25 years, Brad Franklin remembers using bottled water as part of his everyday life in Jackson, Miss. His family didn’t trust the city’s tap water when he was a child, a suspicion that has continued as he raises his own family.

“We use water from the faucet for cooking and cleaning,” he said from his North Jackson home. “But we probably buy two or three crates of water a month for drinking. That’s been part of everyday life for everyone for years.”

But Franklin says that people in the western and southernmost parts of the city have had it far worse because of their proximity to the two main water treatment facilities in the city.

“Life was a bit more chaotic for them,” he said. “They suffered long delays and needed bottled water more than in other parts of the city.”

While Jackson’s water crisis hit its lowest point in August when it stopped working completely, it had been coming for decades, long before the city elected its first Black mayor in 1997. Since then, the boiled water notices have become more frequent and Jackson has become the poster child of a nation struggling to update its aging infrastructure in some of its most underserved communities.

And as the United States continues to trudge toward a greener future and away from the use of fossil fuels, pollution, and plastic, cities like Jackson could be left behind. Over the last 18 months, the country has passed legislation investing $370 billion in confronting climate change and reducing pollution. Recent rule changes by the Environmental Protection Agency aim to cut power plant emissions by 90% between 2035 and 2040 and drastically cut plastic production, coinciding with a major United Nations push to reduce plastic pollution by as much as 80% by 2040.

While that’s good news for Western nations prioritizing infrastructure in all communities, the same can’t be said for the United States. Problems with water continue to plague thousands of communities where relying on basic amenities such as clean and running water makes moving away from plastic extremely difficult.

Flint, Mich., has also relied on the widespread use of plastic bottles to meet its freshwater needs since Apr. 2014, when residents noticed a difference in water quality. The city decided to change the source of its municipal water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The switch caused pipes in Flint to corrode and leach lead and other contaminants into the city’s drinking water. However, the city didn’t advise residents not to drink the water until Oct. 2016. Dozens of people got sick and at least 12 people were killed by Legionnaire’s disease in the water supply in 2014 and 2015. It’s believed the toll could be much higher.

The governor was charged with misconduct in the office relating to the crisis, alongside manslaughter charges for other officials. Nearly every case has been thrown out by judges.

Since then, plastic has been a part of everyday life.

“In Flint, plastic bottled water has been essential for the response to our water crisis,” said Mona Munroe-Younis, executive director of the Environmental Transformation Movement of Flint, a Michigan-based advocacy group that was created in 2018 to fight environmental injustice and address Flint’s ongoing water problems. “But how do you make that societal shift that’s absolutely essential for the good of our health and the planet in a way that doesn’t create these unintended consequences and disparities, especially in Black and Brown communities?”

Munroe-Younis also said she uses a filter at home and refused to drink from plastic bottles while pregnant, concerned about chemicals that leach from plastics. But she also understands that not everyone may have the money to buy specialized faucet filters that can remove lead in the majority Black city. Depending on the quality and use, some filters can range from around $50 for a single faucet up to thousands for a whole house filtration system.

Flint is 57% Black, while 41% of all residents live below the poverty level. The average household income is about $32,000, compared with $71,000 nationwide.

NAACP President and CEO Cornell Brooks drew a direct connection between Flint’s socioeconomic factors and the toxic drinking water.

“Environmental Racism + Indifference = Lead in the Water & Blood,” he tweeted in 2016.

In 2022, the EPA found that residents in many cities needed better information to install and operate filters effectively.

“There’s no perfect answer to this problem,” she added. “But if we’re going to address our growing plastic problem, there need to be complimentary programs that offer filters, education and accessible recycling programs as a stopgap until we can completely overhaul our infrastructure.”

Plastic pollution is an international problem

The United Nations has signed 193 countries to its most recent proposal of drastically cutting plastic pollution. On Tuesday, it released a major study on how the world can move away from plastics and create a circular economy.

The report proposes completely overhauling industries and markets that use plastic and educating the public to help its primary goals of reusing, recycling, reorienting, and diversifying.

“The petrochemical industry, municipalities, informal waste pickers, plastic converters and key users – such as packaging, textile, transport, fisheries and agricultural – can accelerate reuse and recycling and ensure the sustainability of alternatives introduced in the market,” noted Inger Andersen, the executive director of the United Nations environmental program, in the report.

About 300 million tons of plastic are produced annually, including five trillion plastic bags and 583 billion plastic bottles. Microplastics have been found in the deepest parts of the ocean to the top of Mountain Everest. It’s also very likely in your bloodstream and brain.

The road to less plastic won’t be easy

As many as 22 million people spread across all 50 states are still using toxic lead pipes, although those are likely underreported figures, according to the National Resources Defense Council. Other underserved communities, like Jackson, MS, don’t have a lead pipe problem but have been dealing with a neglected water system for decades.

In late August of this year, severe storms in Mississippi caused the Pearl River to flood. It shut down Jackson’s main water treatment facility and deprived 170,000 people in the state capital of clean drinking water.

That’s right, the water system in a state capital of the world’s wealthiest nation failed.

President Joe Biden declared a federal emergency, while analysts said the crisis was preceded by decades of racial discrimination, shifting demographics, and severe infrastructure problems that had been exacerbated by climate change.

The system has been in desperate need of repairs since at least 1997 when Jackson elected its first Black mayor. But the $300 million needed back then to fix the problem had flowed out of the city along with the taxes of its former white residents who fled to suburban cities on the outskirts. That price tag has reached $1 billion, while the reliance on plastic bottled water is still huge among the city’s residents, of which over 80% are Black.

“It’s going to be very difficult to ever get this generation of residents to trust the water supply, even if there is a miracle and it gets fixed,” said Deborah Delgado, who is on the advisory council of the National League of Cities and a councilwoman from Hattiesburg, who helped supply Jackson with tens of thousands of bottles of water after the water system failed in August. “If we moved away from plastic, it would hurt Black communities more because of the lack of amenities and resources, and these people have other issues going on in their lives aside from worrying about where to get water.”

While some might believe it’s possible to address the infrastructure problems in these communities between now and 2040, the evidence suggests otherwise. The EPA issued a lead and copper rule in 1990 that was supposed to address water quality issues nationwide. In 2018 Congress told the EPA to gather data on lead and copper pipes nationwide. By 2022, a new rule was passed that required states to provide that data. They haven’t, and the statutory deadline has passed, according to the NRDC.

Current data shows that the problem is primarily in the northern states and Texas. For example, Illinois and Ohio still have nearly 650,000 lead pipelines. Michigan has almost 500,00, while Texas has 270,000.

But there has been some success. In Benton Harbor, Michigan, a city with an 85% Black population, the city has nearly finished replacing all the lead pipes and reduced lead water levels to within EPA limits. The project has been so successful that the city is now replacing lead in other areas of people’s homes free of charge.

“This community survived on bottled water for years,” said Reverend Edward Pinkney, a community organizer in the city. “It helped us get through the worst of this crisis, but our resilience proves that government negligence and ignorance can be overcome with community action and pressure.”