The answer to education in Florida is in Black history

School bells are ringing across the country, and once again African American educators are showing how they’ve always understood the assignment. It’s one that’s been passed down for generations: to liberate young, Black minds so they can be participants in their own freedom.

Examples of this can be witnessed in classrooms and churches. Sundjata Sekou, a New Jersey teacher who renamed himself after the first king of the Mali Empire and the Mandika word for wisdom, uses hip hop and banned books as tools to disassemble a system wishing to colonize classrooms. Akiea Gross, a Maryland abolitionist, radicalizes early childhood education through their pedagogy, Woke Kindergarten.

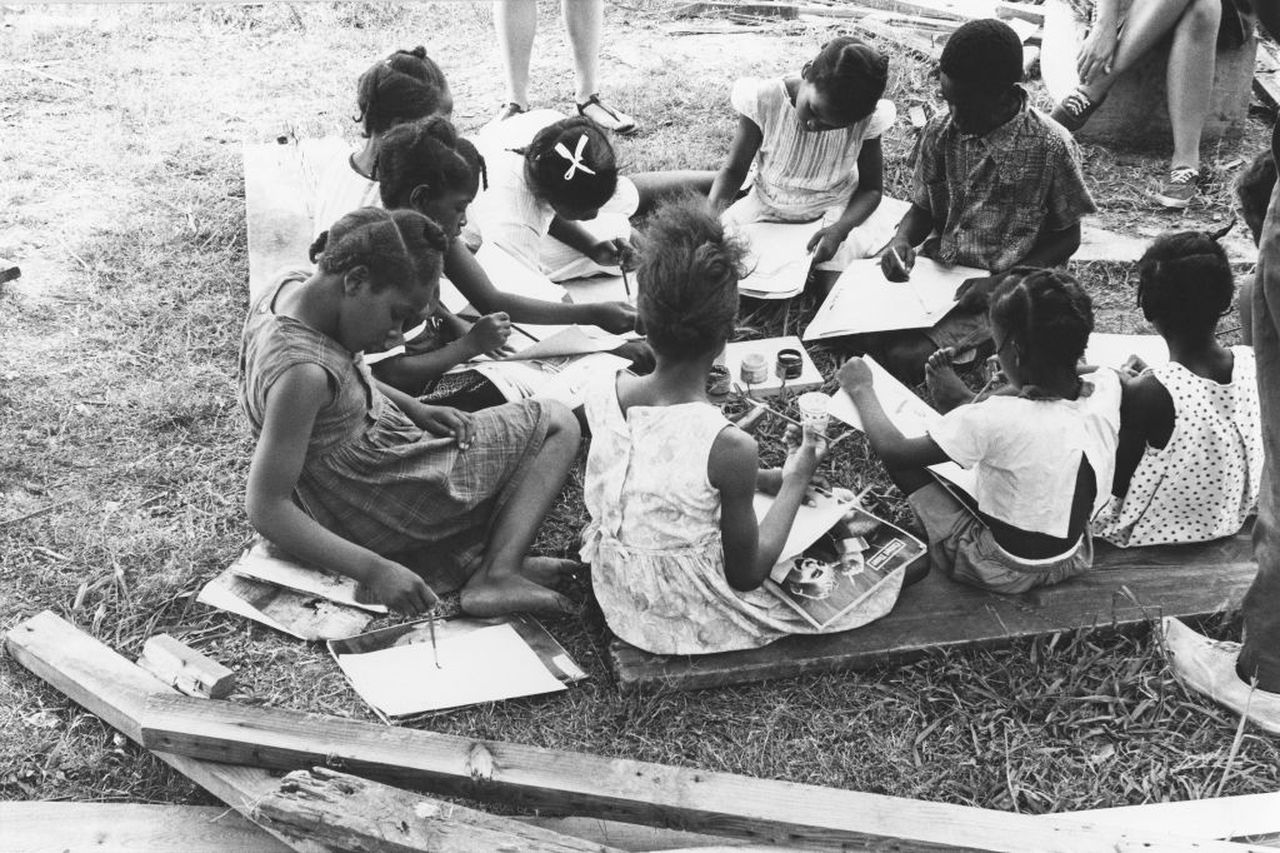

These efforts are Sekou and Gross’ contributions to an endowment of Black empowerment established by the Black educators who came before them. Making space for joy and history to run the classroom mimics the same playbook as Freedom Schools, the education program established by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as part of the 1964 civil rights campaign Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. Dr. Hilary Green, an Africana studies professor at Davidson College who researched the foundations of Black, southern schooling for her book “Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South”, talked about how Black youth and their families were inspired to be foot soldiers of change while attending Freedom Schools. The estimated 3,000 students who attended the 41 Freedom Schools held at churches and homes across Mississippi encountered an education model which honored Black history, celebrated creativity, embraced community care and encouraged independent thought. While the target demographic was school-aged youth, people as old as 80 were sitting in on lessons far more fulfilling – and life-changing – than the subpar education Black Mississippians were receiving at the time.

“These community-based schools were designed to empower the youngest members of society, and also the adults who were conditioned and trained to be like, ‘We’re not going to buck the system. If we do so we will get killed,’” Green said. “How do we convince them to be brave and to fight in a strategic way? By reeducating them. And that’s why I love the Freedom Schools because freedom is what they were aiming for, schools were what they had and they used the talents of the entire community to overcome these community structures and struggles that they were facing as a community.”

Educators of yesterday and today are instructing during disempowering times for Black students, with Florida being the epicenter of recent efforts to limit the instruction of race in classrooms. Gov. Ron DeSantis rejected an Advanced Placement African American Studies course in January due to fears of “indoctrination.” State officials who examined the course and objected to topics concerning reparations, Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ+ history, also attempted to minimize slavery’s impact, according to a Miami Herald/Tampa Bay Times report. Later in July, the Florida Department of Education faced criticism after approving social studies standards requiring middle schoolers to be taught how the enslaved “developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Current attempts to sanitize Black history is a haunting from a ghost of white supremacist past. After the Civil War ended, the Daughters of the Confederacy employed the education system to push a revisionist history which portrayed “happy slaves” and how it was “sad” the Confederate lost the war. This “Lost Cause” narrative was published in Alabama and Mississippi textbooks well up until 1980, Green said. African Americans’ contributions in the arts and other aspects of society were absent from education at that time. Green said this type of instruction had a purpose: to make Black people feel inferior.

“They denied the aspects of Black joy that came naturally within the Black community,” Green said. “None of that’s being taught. Instead, it’s a message that they’re uneducated, unintellectual, contributed nothing to the development of the nation and therefore don’t get any rights. How do you convince someone who read these history textbooks to even want to go to high school because the books tell them that they have no future – that they don’t matter in the development of the nation.”

Freedom Schools intercepted this indoctrination by creating a curriculum featuring Black history, art, media, and stressed the importance of critical thinking. In a memo proposing the Freedom Schools to SNCC, activist Charlie Cobb Jr. stressed the goal of the school, which was to help students become a force of social change in Mississippi.

“If we are concerned about breaking the power structure, then we have to be concerned about building our own institutions to replace the old, unjust, decadent ones which make up the existing power structure,” Cobb wrote. “Education in Mississippi is an institution which must be reconstructed from the ground up.”

Students were reinvigorated by the works of Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. They were inspired by the legacies of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and other Black heroes. They were emboldened by the histories of enslavement revolts. The citizenship curriculum encouraged students to think critically about their environments, the struggles they faced and the nonviolent solutions to those issues. These lessons changed how Black children saw their past, present and future. A Freedom School teacher mentioned in a weekly report students’ reaction as they challenged the myths they originally learned about Africa.

“Already some students have expressed delightful surprise at the fact that their ancestors were not so close to savagery as they (the students) had imagined,” the teacher reported. “I have not argued that there were not in some parts of Africa some primitive cultures, but I have distinguished between primitive and savage.”

Green said creativity and play were woven into instruction time, giving Black students a framework to voice their dreams, hopes, opinions and fears. A typical school day started with singing freedom songs. The lyrics filled children with hope despite their struggles:

We shall overcome someday.

We shall not be moved.

Facing the rising sun of a new day begun, let us march on till victory is won.

Students carried on this energy into their artistic works. In a booklet of poems written by Freedom School students in honor of Emmett Till, 15-year-old Edith Moore encouraged her classmates in her piece “Fight On Little Children.”

In the end you and I know

That one day the facts they’ll face.

And realize we’re human too

That freedom’s taken slavery’s place.

Students not only read about life and culture from Black publications such Jet and Ebony magazines, they were also encouraged to create their own forms of media. In section five of “News About Freedom,” a newspaper created by a Freedom School in Mt. Olive, Miss., students published essays about how they envisioned their lives in the future. They imagined themselves as mechanics with their own shops, librarians with homes full of books, educators who taught the young and old, doctors who cured diseases, nurses who aided the ill, pilots who flew across the country as free people, and a few of them dreamed of being young men and women who were registered voters and school integrators. After owning the prettiest home in California or Illinois, Magdalene Randle wrote, “And I also want to be a SNCC leader.”

When delegates from all the Freedom Schools came together for the final statewide conference in Meridian, Miss., the adults noted how the Black youth took over the event. The youth laid out a political strategy that tackled issues like segregated housing, education and public accommodations. Green said the educators gave students permission to dream big by allowing them to be leaders in their Freedom Schools. They took that training to transform their lives.

“They were being educated to think, ‘You can do anything. Nothing’s gonna stop you except for your own imagination.” Green said. “It was a shared authority model and it didn’t matter your age or circumstance. You can participate.”