Sumter County delays first day of school after board refuses to hire staff

Sumter County will now push back the start of classes to Monday, officials announced this afternoon, due to shortages of teachers and bus drivers. But unusually, the shortages weren’t because the district couldn’t find staff — it was because the school board declined to offer anyone contracts.

Schools announced on social media Wednesday afternoon that class had been delayed “due to county-wide shortages in instructional and transportation staff.” It’s still unclear whether students at one of the local middle schools will transfer buildings, as initially planned.

“What’s going on now, it’s not about the children,” Charles Wideman, a parent of Sumter County graduates, said Tuesday after a school board meeting that lasted three minutes.

Read more Ed Lab: See your school district’s math, science, reading scores.

On Aug. 8, district leaders in Sumter County met with several important decisions to make, days before the planned start of school on Aug. 10. They needed to approve hires, new curriculum and the shift of middle school students from one building to another.

Instead, the school board effectively stalled all decisions for up to a week. Board members Sharon Nelson and Beretha Washington voted against approving the meeting’s agenda. The board president, Jeanette Brassfield-Payne, was absent that night, preventing a majority vote. Wideman’s wife, Lillian Wideman, is a board member who voted to approve the agenda.

‘This is sad’

Parents packed into folding chairs in a small, wood-paneled board room Tuesday evening. Superintendent Marcy Burroughs, who was hired in July, wanted to give a presentation that detailed her plans to get the schools back on track. Just a few days prior, state officials announced plans to take over the rural, Black Belt district. The district has struggled for years with financial issues, declining enrollment and low test scores.

“It’s political. It’s selfish. It’s nonsense,” Bridgett Ward, a parent of two high school students, said in the parking lot that evening as other parents gathered outside.

Ward’s daughter is a senior at Sumter Central High School, and her son is a junior. She said schools are struggling to hire teachers for courses her kids need to graduate. On top of that, she said, many of the elementary and middle school facilities are in desperate need of repair.

Read more Ed Lab: Some high-poverty schools do succeed. Here’s how.

She believes some members on the local school board are intentionally voting against efforts to improve the situation.

“[The state] should have been here years ago,” she said. “Dr. Burroughs is trying to set it right, but they’re just having so much backlash from the people who don’t want to change.”

Charles Otis, a Sumter County alumnus, is considering running for school board to make sure those plans can actually happen.

“This is sad,” he said. “You’ve got teachers to hire at all of the elementary schools and you’ve got other employees that need to be in place so you can operate your school year. Without that transpiring, you’ve got a problem.”

‘Are our students worth it?’

After the meeting abruptly ended, and as parents continued to congregate in the parking lot, Burroughs motioned the crowd to go back inside.

She was going to show them her presentation anyway.

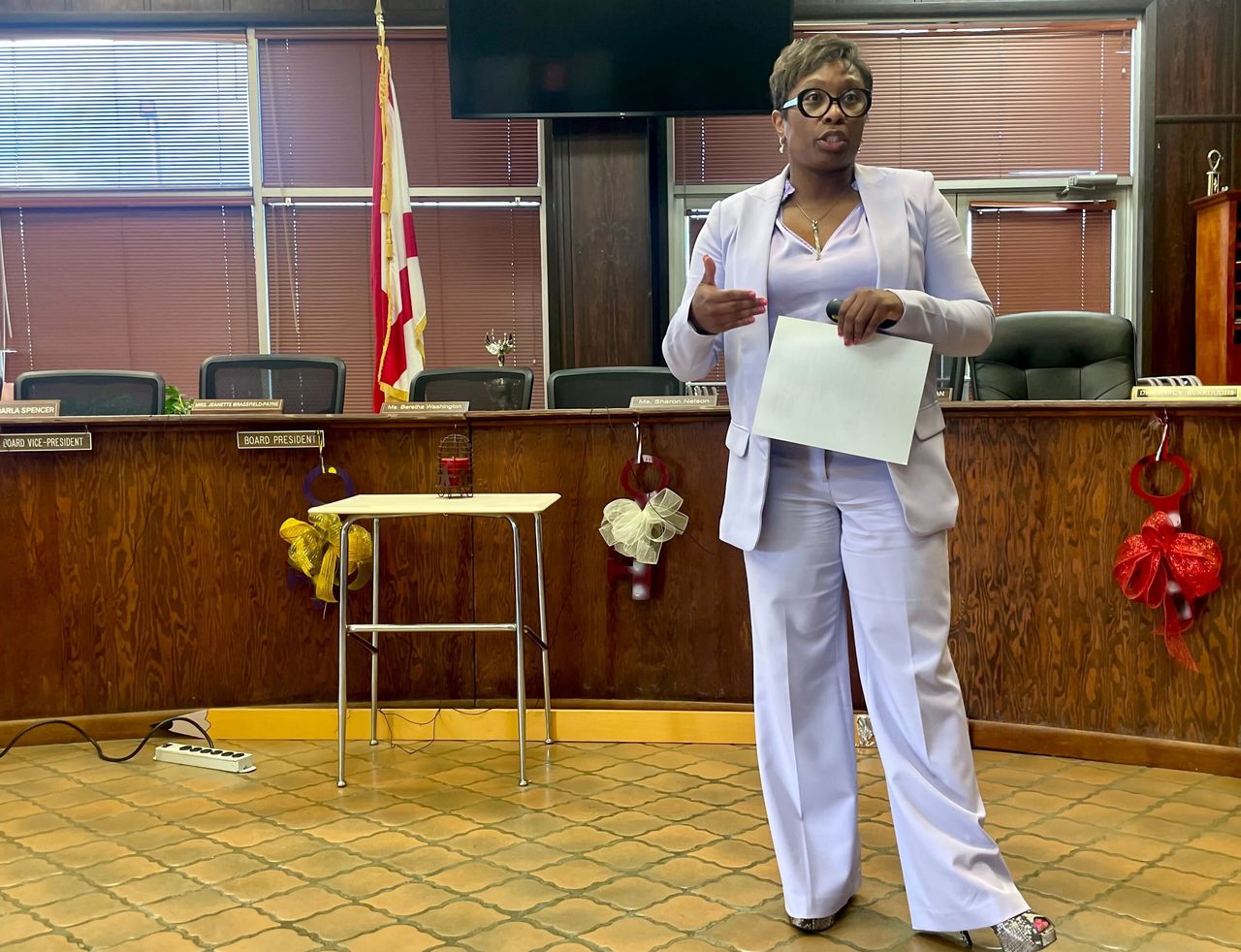

Superintendent Marcy Burroughs speaks to a group of Sumter County parents and community members in Livingston, Alabama, on Aug. 8, 2023. The school system is in danger of a state takeover after years of concerns about performance, record keeping and facilities. Rebecca Griesbach/AL.com

“This is not a blame game,” she said as she flipped through slides that showed the district’s dismal reading, math and career readiness scores. “This is not pointing fingers. This is about identifying and acknowledging that there is a problem.”

Burroughs, a Black Belt native, took the superintendent position with a goal to drill down on data and make research-based interventions. She’s a former school improvement specialist who had been working with the high school since 2020, in an effort to get it off what was then called the “failing schools” list.

Sumter Central High School and Kinterbish K-8 in Sumter County are among two of the 13 schools statewide where no students scored proficient in math on the spring 2023 state tests. And while about 90% of students graduated last year, barely half were deemed college and career ready.

Burroughs walked parents through the data for each of the district’s four schools, breaking the numbers down by grade level. She showed them just how many students – not percentages – were proficient in each subject.

“Look at math,” she said, pointing to the middle school math scores. One out of 62 sixth graders were proficient last year. “These babies are going to the seventh grade this year! Look at seventh grade, how many? One. One baby out of 84 students.”

Fixing the problem, she said, would take a lot of time and effort. It would involve owning the data, following detailed guides and creating new, organized lessons that follow state standards. And hiring more teachers, Burroughs added.

“Is this going to take a lot of work? Yes. But are our students worth it? Yes.” she said to the parents, asking them a moment later: “Are y’all going to work with me to fix the problem?”

“Oh yes!” the crowd chimed back.