Sister of ailing Alabama inmate says medical furlough process is broken

The sister of an Alabama inmate suffering from lung cancer said the Alabama Department of Corrections denied an application for medical furlough and is instead allowing her brother to suffer and die in prison.

Antonio Smith was transferred from the Red Eagle Community Work Center to the Kilby Infirmary after his diagnosis. The family applied for medical furlough, the program that allows for the release of certain older or terminally ill inmates. In May, they found out Smith had been denied.

His sister, Travella Casey, provided medical records that showed Smith began complaining of back and shoulder pain September 2022, but didn’t receive a biopsy until March. He had a chest CT scan in December and a PET scan in January that showed a mass in his lungs.

“The time frame that they chose to respond, it was almost six to seven months,” Casey said. “I just think they dropped the ball with him.“

The medical records show that oncologists at Alabama Cancer Care of Montgomery began consulting on his case in late March. He began receiving chemotherapy in May, the records show.

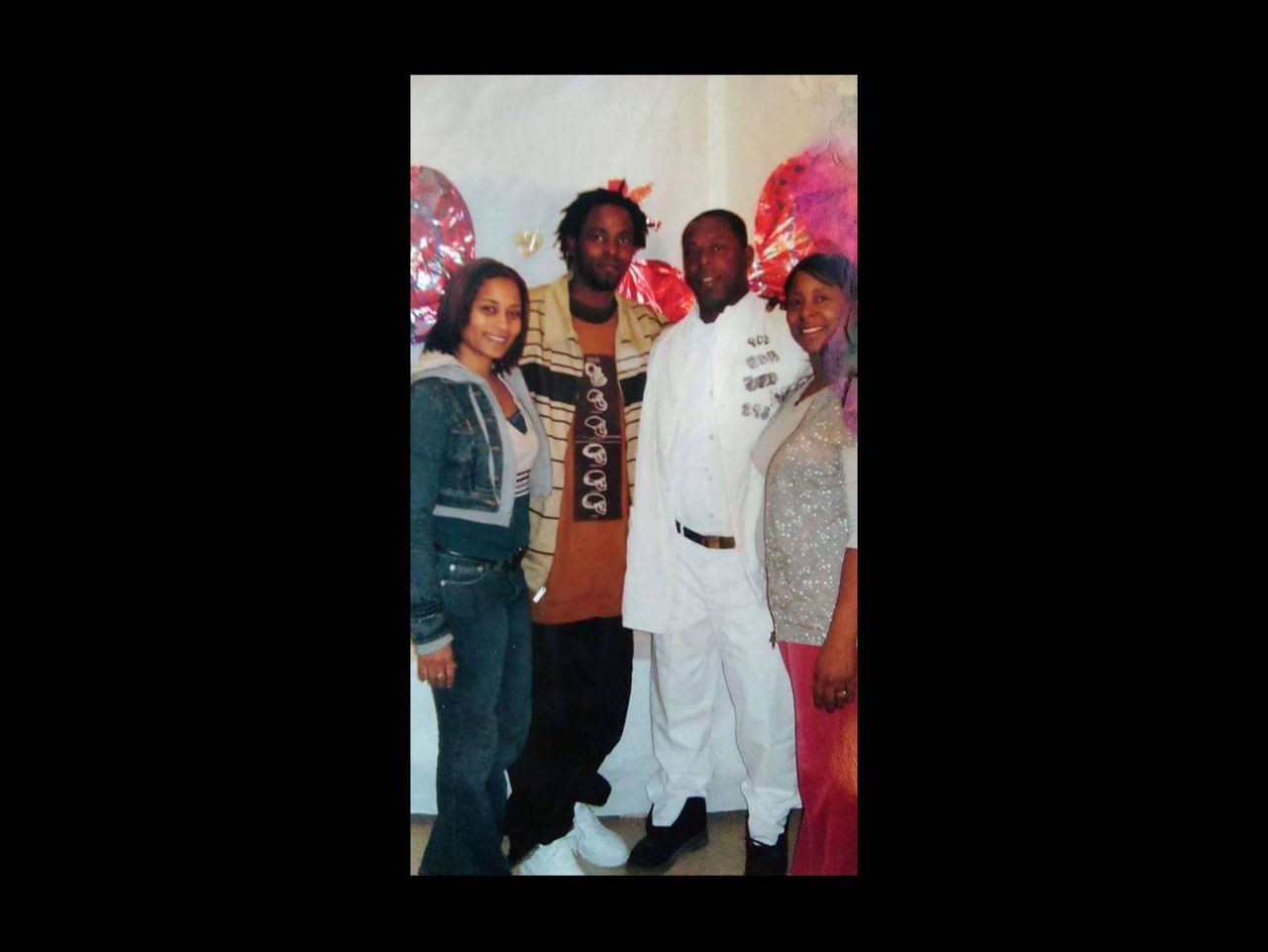

Casey said she speaks with her brother almost every day. He had a good disciplinary record at the Alabama Department of Corrections and was incarcerated on a minimum security honor farm before he became ill, she said.

“He was moved to a maximum-security prison two weeks ago because his condition can’t be treated at the honor camp he’s been at for the last few years due to good behavior,” Casey said. “He’s getting worse by the day and it’s like he’s been taken there to die.”

Casey said her brother has been struggling with severe cancer pain that keeps him up almost all night. She said he only sleeps about two hours. She said he asked to have a feeding tube inserted so he would stop losing weight.

Inmate healthcare “and other professional services” cost the department $221,765,318, according to a 2021 report from the Alabama Department of Corrections. That’s just over a third of the prison’s total expenditures and the most money the department spent on anything.

Smith was convicted in 2000 for murder in the shooting death of his live-in girlfriend, LaKendra Kirkland, in Dothan. A Houston County judge sentenced him to 99 years in prison.

He and his siblings were born in Alabama but were sent to New Jersey as young children to live with relatives after the murder of their 4-year-old sibling. They returned to Alabama as teens and reunited with their mother, Casey said.

In court files, Smith argued that he should have been charged with a lesser offense and said the shooting was accidental and happened during a domestic dispute. He was 22 when he was arrested and had not been in trouble before, Casey said. A judge denied his petition for a new sentence.

Smith has finished several education programs for inmates. Members of the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles denied his bid for parole in 2021. His attorney, Frank Ozment, has helped Smith appeal that decision.

Parole rates have plummeted in recent years, after three brutal murders in north Alabama committed by a man who had recently been paroled. Smith’s case was reset to 2025, but his sister and attorney worry he won’t live long enough for another hearing.

“He’s getting worse in a hurry,” Ozment wrote in an email. “He’s getting opioids for pain management from Kilby medical, but that suppresses his appetite and causes severe constipation, so he’s getting malnourished.”

A spokesperson for the Alabama Department of Corrections said Smith was receiving appropriate medical treatment in prison. Late last year, officials from the department announced they would switch medical service providers from Wexford to YesCare Corp.

Casey said she thinks the corrections department moved too slowly to investigate her brother’s complaints in 2022. It took six months to get a biopsy after he first complained of pain, and by the time the results came back, they showed the cancer had advanced to stage 4.

Alabama officials rarely use the medical furlough program that allows sick and elderly inmates to leave prison when they are no longer a threat to society. Only seven inmates qualified for the program in the first 10 months of 2022, according to Al.com

“We can’t change what God’s plans are, but I don’t want him to sit in there and die when more could be done,” Casey said. “We’ve already lost one sibling and I don’t want him to pass away thinking he has no one.”