Senator proved his mettle when he said the word ‘depression’

I’m not steeped in Pennsylvania politics and generally wouldn’t have cared a whit about the men who were vying for the chance to represent the Keystone State in the U.S. Senate. But there was something almost magnetic about that 2022 election, and as Election Day drew near, I and many other nonresidents began to care.

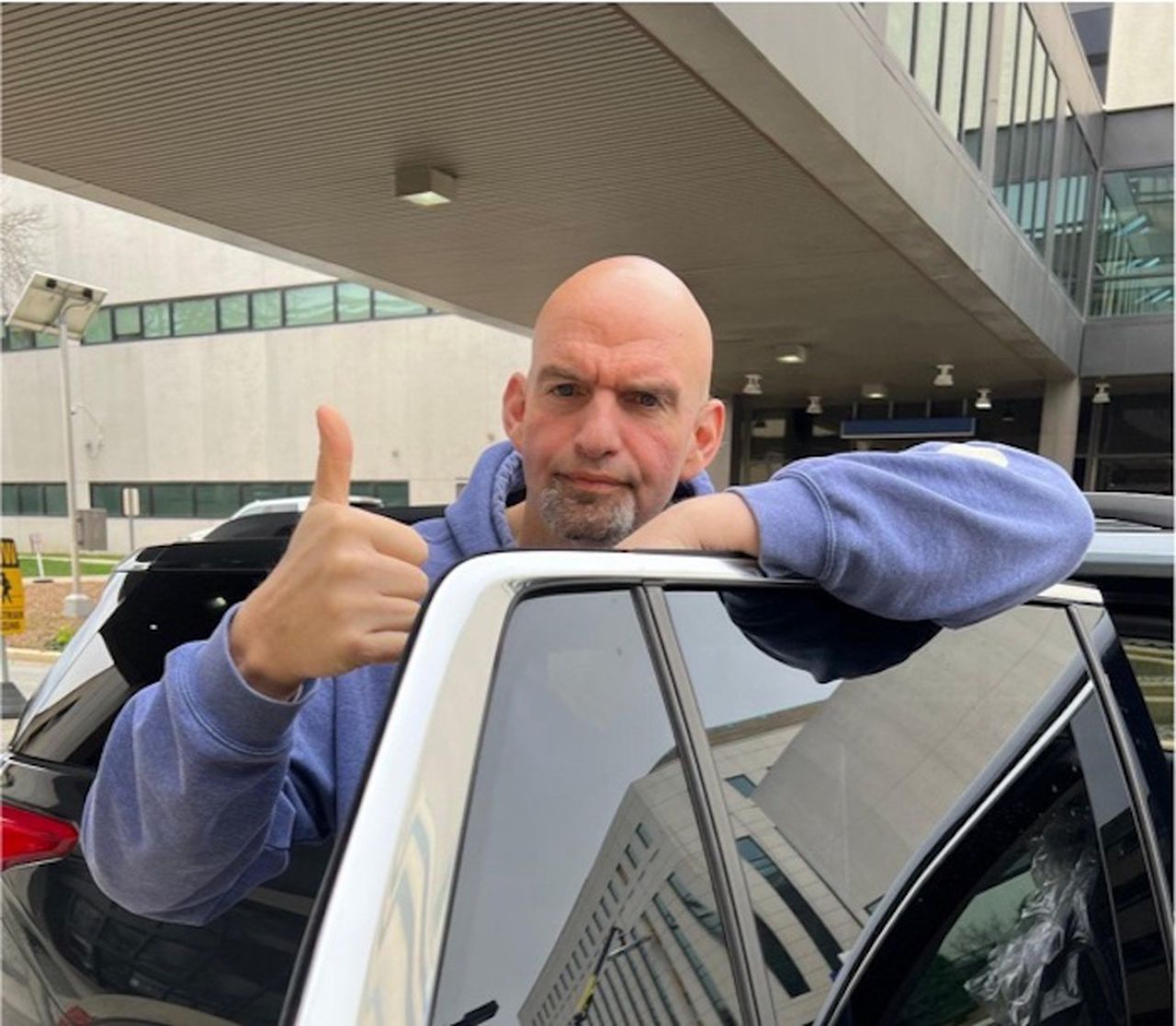

Was it the fact that the candidates couldn’t have been more different if they had set out to be? On the donkeys’ side of the ballot, you had John Fetterman, a tatted-up guy who scowls even when he smiles. His answers to reporters’ questions were intriguing at least in part because they didn’t always make a lot of sense.

And on the elephants’ side, there was Mehmet Oz, known to admirers as “Dr. Oz.” He’s never held public office. He has exquisitely coiffed hair and eyebrows so remarkably high that they rival the Gateway Arch, giving him a look of perpetual astonishment. Most bios on him begin with “television personality” and note that his stardom is courtesy of Oprah Winfrey.

I was rooting for Fetterman because he was the underdog — the anti-smooth, anti-sophisticated candidate who, although he had served terms as a mayor and then as Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor, managed to position himself as the anti-politician. When he suffered a major stroke just six months before the election, however, I figured he was a goner, politically speaking.

So when he won, I was as surprised as pundits, prognosticators and Dr. Oz. Apparently, enough voters had identified with Fetterman’s assertion that, like many of them, he’d gotten “knocked down and had to get back up,” to give him the victory, albeit by a slim margin.

Underdogs, TV stars and political surprises aside, however, the campaign wasn’t where we learned what the new senator is made of. That came several weeks ago, when he proved his mettle by checking into Walter Reed Hospital for depression.

Yes, depression. We talk about it a little more openly than in the past, but only a little.

Granted, it’s not the family shame and career-killer it used to be. People above a certain age may remember the 1972 presidential election, when Democrat George McGovern picked Missouri Sen. Tom Eagleton to be his running mate, without doing any in-depth vetting of him. Turns out, Eagleton had been hospitalized for depression three times in the Sixties and also had undergone electroshock treatment.

You would’ve thought he had been treated for leprosy.

The public’s and media’s reactions were immediate and visceral. Eighteen days later, Eagleton was off the ticket. McGovern’s staff professed to be concerned about the fact that if something happened to incapacitate the president, the man with his finger on the nuclear button would be a man who suffered from Oh-my-God-MENTAL-ILLNESS.

I get it that this is not the 1970s, and that since then, numerous medications have been developed to effectively treat depression and other mental disorders with few side effects. People who seek treatment for their depression can hold down a job, have a normal family life and get through the day without feeling like they’re tethered to a 500-pound boulder.

I know what it’s like to be tethered to that boulder, by the way. I spend my childhood as the daughter of clinically depressed parents, both of whom self-medicated with alcohol. Every now and then, they were hospitalized.

As for me, I clearly remember the time in my early 40s that I visited my doctor to describe a variety of symptoms, including insomnia and low energy. When she said, “Frankly, I think you’re depressed,” I burst into tears at the thought of having inherited my parents’ curse.

I soon learned the difference between living in an era where little effective treatment existed and living in a time where effective treatment is readily available, and between living in an era where nobody talked about depression and living in a time where mental illness is considered just that — an illness.

It’s not a curse, a scandal or a shameful condition.

Sadly, some people haven’t read the memo, however, and either don’t understand or don’t want to understand what mental illness is. John Fetterman, on the other hand, gets it — because he’s got it.

He set a bold example when — instead of struggling quietly or resigning from office or seeking treatment on the sly — he announced that his depression had gotten so bad that he needed to be hospitalized in order to stabilize it.

More than 50 years after Tom Eagleton was forced to resign from the Democratic presidential ticket, John Fetterman made no excuses or expressed any shame.

No embarrassment.

Just the truth.

Not bad for a scowling, tatted-up, anti-smooth, anti-political underdog, wouldn’t you agree?

Frances Coleman is a former editorial page editor of the Mobile Press-Register. Email her at [email protected] and “like” her on Facebook at www.facebook.com/prfrances.