Safe Haven box intended to save infants at risk of abandonment

The second Safe Haven Baby Box in Alabama was opened with a ribbon cutting at Fire Station No. 4 in Prattville on Thursday.

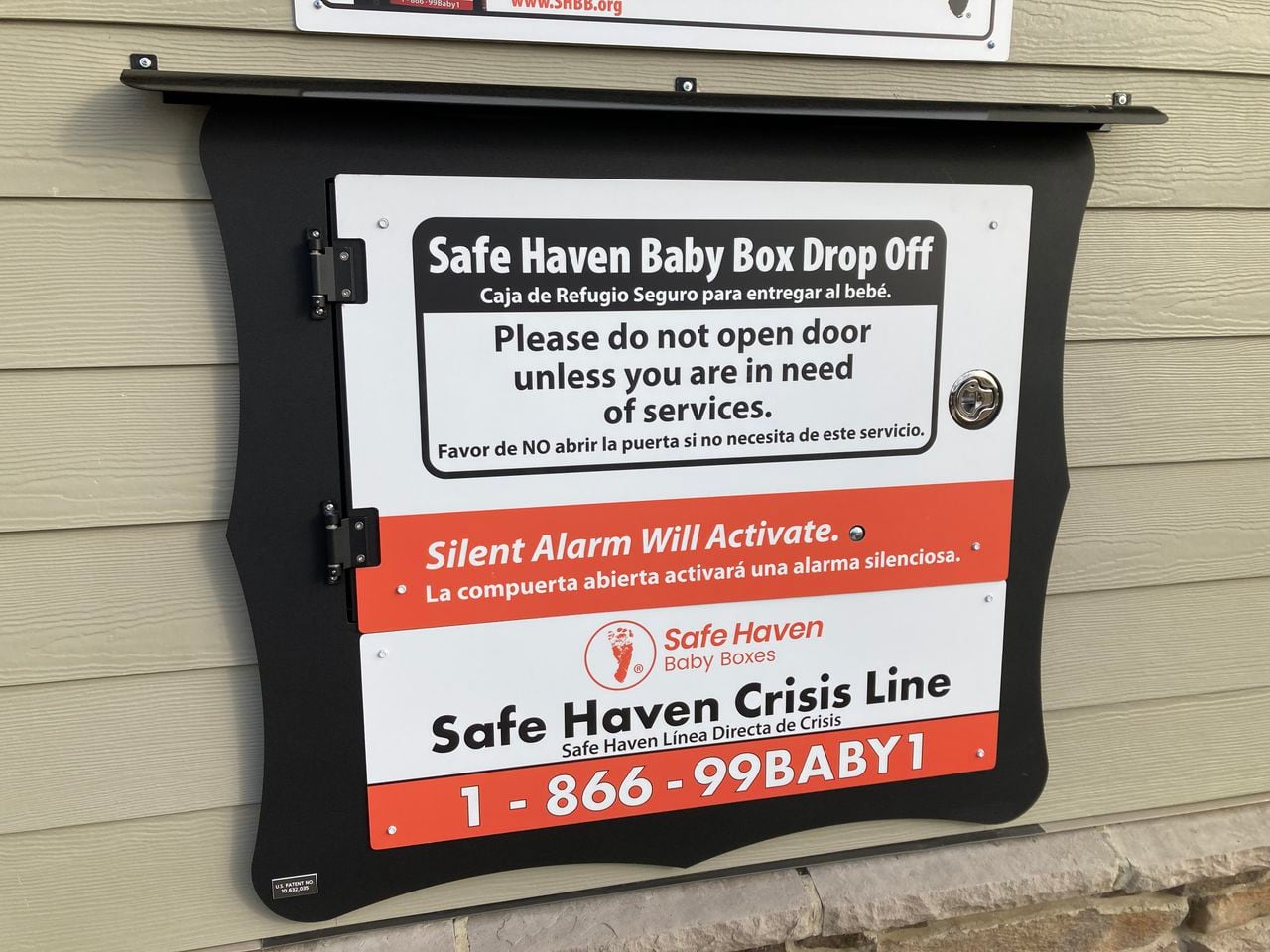

Safe Haven Baby Boxes are designed to allow the safe surrender of an infant, anonymously and with no questions asked. The idea is to provide a life-saving alternative for a desperate mother who might otherwise abandon an infant in an unsafe place.

The boxes were developed by Monica Kelsey of Woodburn, Indiana, a retired firefighter and medic, who came to Prattville for Thursday’s event.

Kelsey was abandoned two hours after she was born in 1973 by her teenage mother, whose pregnancy was the result of a brutal rape. Kelsey said she considers herself on the front lines of a movement to save other infants who are at risk of abandonment.

“This is my legacy and I am their voice,” Kelsey said. “And I will forever be their voice. And I tell you it is an honor, it is an absolute honor to speak for them.”

The Alabama Legislature passed a bill last year to authorize the use of the boxes in Alabama, expanding a law passed in 2000 that allowed the surrender of infants at hospitals.

The first Safe Haven Baby Box was opened in Madison on Wednesday. The Kids to Love Foundation, based in Madison, is spearheading the Safe Haven effort in Alabama. Kids to Love Founder and CEO Lee Marshall said donors have provided funding for a total of 13 baby boxes in Alabama.

Marshall said Kids to Love is talking to city officials and firefighters across the state to have boxes available in more places.

“I think the biggest challenge right now is people don’t really understand it,” Marshall said. “They don’t understand how it works and that there are so many built in safety factors.”

The box, installed in the exterior walls of fire stations, opens with a handle from the outside. Inside the climate-controlled box is a bassinet. When closed, the box locks from the outside and sounds an alarm to alert firefighters that an inmate has been placed there.

Marshall said the box is also wired to place a call on its own secure line to 911.

“They have protocols set up so that if they’re not here there will be someone from another station to be able to get here,” Marshall said. “We’re looking at about two and a half minutes response time is what they shared with us earlier when they tested it through the 911 call center.”

Marshall said the Alabama law allowing surrender of infants at a hospital, in place since 2000, was a good step, but the expanded law with the use of the baby boxes has the potential to save more lives.

“We felt like while that is still a great option, hospitals are crowded,” Marshall said. “And sometimes this is a decision that they don’t want an audience for. So there is complete anonymity when they choose to place their baby in a baby box.”

Kelsey said a total of 39 infants have been surrendered in Safe Haven Boxes since the first was installed in her hometown in Indiana in 2016. That includes 17 surrendered in 2023 alone as the number of boxes has grown. Kelsey said another 133 infants have been surrendered directly to firefighters.

There are 193 active boxes nationwide and about 47 more in some stage of installation or testing, Kelsey said.

Rep. Donna Givens, a Republican from Loxley, sponsored the bill to allow the use of Safe Haven boxes in Alabama. Givens said she got the idea at an event where she heard Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch talk about her state passing the same law. Givens said she talked to Fitch, then started working on legislation.

Givens is a freshman lawmaker elected in 2022 and said she prayed about finding her purpose for the legislative seat. She said despite her inexperience as a brand new member of the House and limited days in the session after she introduced the bill, the legislation passed the House and Senate without a dissenting vote. Givens said a reporter asked her how the bill made it to the finish line despite the obstacles.

“I said there’s only one thing,” Givens said. “If God is in the middle of something, man can’t stop it. And I truly feel like God was in the middle from the beginning to the end of the entire process because it would not have happened.”

Givens said it is regrettable that there is a need for the Safe Haven boxes.

“Yes, it’s sad times that we have to have something like this. But we’re in those times,” Givens said.

Kelsey said she got the idea for the boxes when she saw one at a church while traveling in South Africa.

“I thought, ‘Why does America not have this?’” Kelsey said. “So on a flight back from Cape Town South Africa on a Delta napkin, 35,000 feet in the air, I hand drew my version of the baby box and then I came to America and started the uphill battle of implementing it here in the country.”

Prattville Fire Chief Terry Brown said he would encourage other fire departments to install the boxes. Brown said the boxes fit with the mission of the fire department to protect life.

Kelsey said it always touches her deeply when she learns that a child has been safely surrendered. She is also mindful of the impact on the life of the mother who made that decision.

“It never gets old getting a call from a fire chief when they say, ‘Monica, we just got a baby in the box,’” Kelsey said. “It’s so encouraging but it’s also so heartbreaking at the same time. Because yes, we’ve saved the life of a child. But we also know that there is a mother that is having the worst day of her life.”

Marshall said the family of Curtis and Dawn Pilot of south Alabama donated the funds for Alabama’s first 10 Safe Haven boxes in memory of their daughter, Nikki Pilot Carlisle, who died of cancer. Maury Carlisle, Nikki’s husband, was recognized at Thursday’s ribbon cutting.

Marshall said Bill Roark, co-founder of Torch Technologies in Huntsville, donated funds for three more Safe Haven boxes.