Roy S. Johnson: Parents should influence their children’s education, at home

This is an opinion column.

Parents should have a say in their children’s education—and they do. Mine certainly did. Mom was a teacher.

They called the class “speech” back then at Paul Laurence Dunbar Elementary in Tulsa.

Today, it’s English—readin’, writin’, and understandin’. “Basics, y’all,” Gov. Ivey would maybe say.

Mom was a substitute teacher during my early years, working part-time before becoming full-time after my father grew ill. (I was in seventh grade when he died.)

In fifth grade, she was my teacher.

She gave me no breaks. Zero. Truth is she was harder on me than the other kids (my story and I’m sticking to it). Harder than any other teacher. (Well, except for my aunt, who also taught at Dunbar.)

To that point, I’d gotten all A’s. (Yeah, I was that kid.) Every report card. I was partly incentivized by my dad, who promised me a dollar for every A from the moment I began school. He feigned grumbling and reached for his wallet each time I gleefully handed him my card. (Little did I know then all the life lessons he was subtly imparting.)

One of our speech class assignments was to memorize a poem. I can’t remember which poem—I probably blocked that evil devil out of my memory—or even the poet. Whatever it was, when it was my turn to recite it in front of the class, I flubbed a line toward the end. Forgot the last few words. Didn’t finish.

Mom didn’t say a word. Didn’t prompt me at all. She just looked down at her paper and wrote something, presumably by my name.

You know where this is going. When I received my next report card, the letter “B” jumped out toward me like one of those annoying pop-up greeting cards.

I survived, of course. I got 50 cents from Dad for the B. (Cs got a whuppin’, back then.) While the B didn’t stifle my educational journey, I never let Mom forget it. I told her she “traumatized me,”; I would have grown to six feet, I told her, had she not given me that B. It was our friendly joke for the rest of her life.

Parents should have a say in their children’s education—and they do. A profound one. At home.

Back then, at a time still infected by Jim Crow, many Black women were teachers. That and nurses. Those were the primary professional lanes open to them—back then.

We were surrounded in segregated North Tulsa by teachers, it seemed. By teachers, women, and men who taught us every day. By how they lived. How they navigated a world that diminished them, legally.

By how they poured into us.

Your children’s education begins with you. With them observing you. Every day. Observing how you walk in the world. Observing how you work and provide. Observing how you treat others. Observing how you spend your leisure time, at play. Observing what you read, what you watch, what you say. Observing your circle of friends, how you engage with one another.

Observing you at church.

Parents are always teaching. Always. Whether they acknowledge it or not.

Whether or not they can help their kid with homework anymore. Still teaching.

Maybe even more so than the teachers so many parents and lawmakers now want to control.

Maybe the most fundamental aspect of educating your child is this reading to them. Reading to them long before they recognize words themselves. Reading to them when they only know your voice. When they hear words you believe are important to them, words that comfort them, that elevate and enlighten them.

Mine certainly did.

I certainly have no recollection of what books my mom read to me and my baby brother as toddlers. I do recall the bookshelves at home were filled. Included was that monstrous set of Encyclopedia Britannica that was in so many homes. Back then. Sometimes I’d just pull one out and read. (Yeah, I was that kid.)

Parents should have a say in their children’s education—and they do. A profound one. Not, though, by yanking books from schools and libraries because, well, they don’t like what’s on the pages. Pages that have been read, vetted, and approved by educators licensed to educate.

Not all parents are doing this, certainly. Or like it. Not even a preponderance of parents. A recent Fox survey found 60% of parents thought the banning of books by school boards was a “major problem”. Yes, Fox.

Let me say this now: The folks selecting schoolbooks haven’t always gotten it right. Especially history books, which we all know now were curated for generations as if much of what happened didn’t.

Or to sugarcoat the truth enough to rot our insides.

That’s changing, slowly but thankfully. Children are finally being taught a broader truth about our past and seeing today through a broader lens.

That scares some folks. A parent or few. A parent who’d rather keep their child in a dark box than allow them to learn whole truths then equip them to navigate it. To discern it. For themselves.

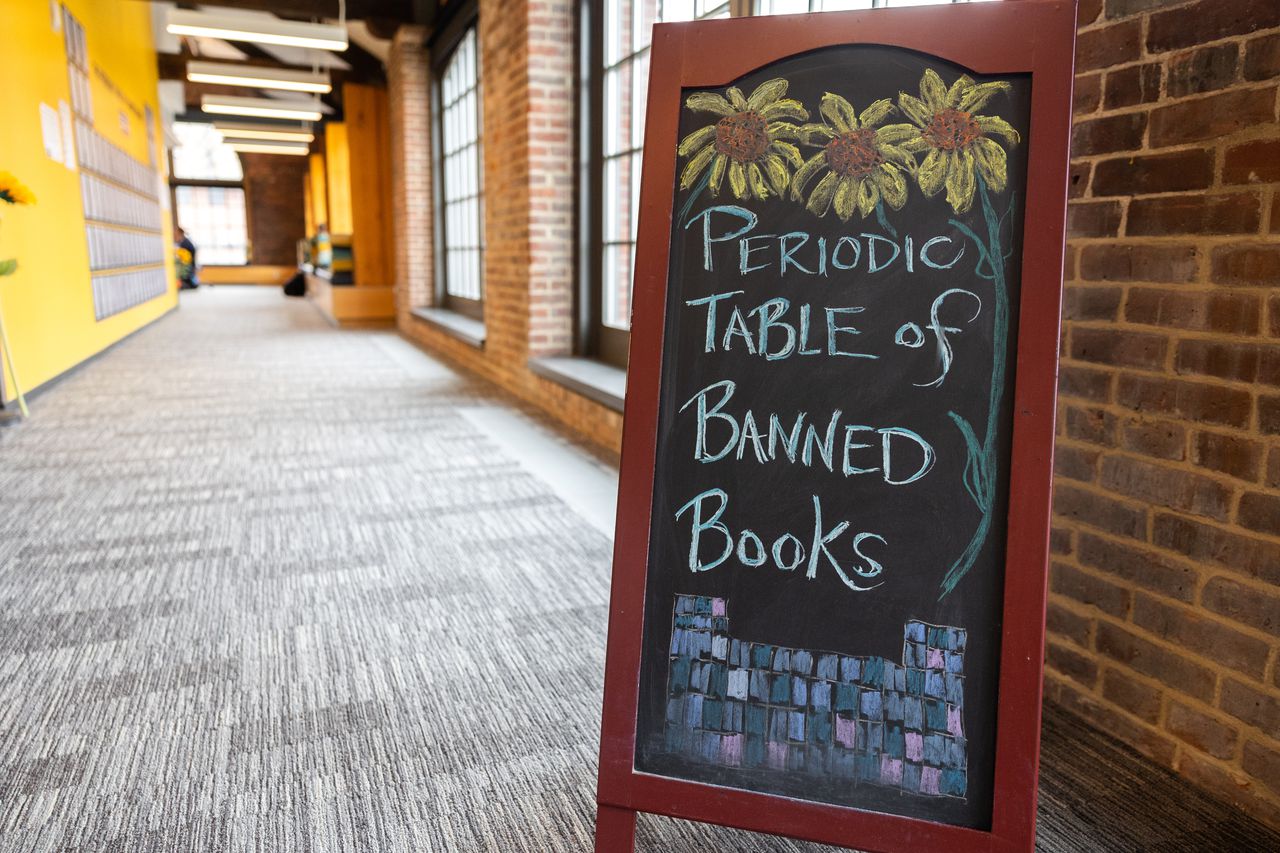

The Periodic Table of Banned Books sign at Springfield Technical Community College’s library. (Hoang ‘Leon’ Nguyen / The Republican)

Message to them: If you object to a particular book, ask the school that your child not have to read or study it rather than stripping from every other child’s educational path—against their parents’ wishes.

Like Shelby County parent Daniel Hill, a one-parent crusade that pulled “Call and Response: The Story of Black Lives Matter,” written by New York Times best-selling author (and friend, full disclosure) Veronica Chambers, from the curriculum at his daughter’s middle school.

RELATED: Book bans are a local affair in Alabama schools. That could change.

What about the other students? Do their parents matter?

Who’s creating laws to protect their rights? Not anyone in Alabama. Or other states where book banning is growing as accepted as the family bar-be-que.

Besides, more than likely, the kid will likely wonder what you don’t want them to know and find the book with their phone.

If there’s a speaker you feel your child shouldn’t hear, keep them at home rather than demanding the speaking be canceled, stripping their words, thoughts, and ideas from every other child’s educational path—against their parents’ wishes.

They do matter.

Parents should have a say in their children’s education—and they do. At home, where children learn from what they see and hear. From their parents.

Which might be the very best reason educating some children should be left to the experts.

More columns by Roy S. Johnson

Questioning parenting after youth violence is real, but does not absolve lawmaker inaction

Why are our Black children shooting our Black children?

Tell me why, Republicans; or do silence and gun deaths speak for you?

I got it wrong; Republicans actually do want us to vote

MLK’s ‘Letter from Birmingham’ Jail’ is not divisive, should be taught in all schools

Attack on trans influencer by Republican female governors is beneath the office

I’m a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and winner of the Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts: “Unjustifiable,” co-hosted with John Archibald. My column appears in AL.com, as well as the Lede. Stay tuned for my upcoming limited series podcast Panther: Blueprint for Black Power, co-hosted with Eunice Elliott. Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, The Barbershop, here. Reach me at [email protected], follow me at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj