Roy S. Johnson: For one man, Birmingham’s ‘tiny’ shelter initiative for unhoused evokes tears

This is an opinion column.

The tears were there. It took all Don Lupo could muster to keep the moisture welling in his eyes from rolling down his cheeks.

It took all he could muster to not rewind what those eyes have seen in a job that became a purpose, a job that began just before the turn of this century, a job he’s held under four Birmingham mayors—a job he’s become.

It took all he could muster to not recall, at the age of 16 walking into his home in Decatur, after spending the night with his grandfather (grandmother has been out playing bridge) and finding his 36-year-old mother dead on the couch. To not recall the legacy she left behind.

Call it what you will—the chronically unhoused, the homeless. By any name, no one exemplifies the deepest desire, the unvarnished passion to elevate the lives of our swelling unhoused population than the 71-year-old grey beard standing before the City Council on Tuesday as he and other members of Mayor Randall Woodfin’s administration shared a proposal to purchase 50 tiny houses—small, lockable shelters with air-conditioning, heating, a desk, and other amenities—for villages where the unhoused can lay down their heads under a roof they can call home.

RELATED: Birmingham city council approves mayor’s plan to offer tiny shelters to homeless

There remain copious questions. “To be determined,” Woodfin said several times responding to councilors’ queries. Yet even at this pre-preliminary juncture, the plan is unquestionably the most vital effort to substantively impact our growing unhoused residents in the city’s history—16 years after a capable and earnest group of 28 public and private leaders, under the direction of Mayor Bernard Kincaid, published a robust 10-year plan to “prevent and end chronic homelessness” in the city by 2017.

A plan that now, via the saucy words of Councilor Valerie Abbott, who’d been on the council six years when the Kincaid plan was produced, “sits on a shelf, covered in dust or maybe burning in a landfill.”

It took all Don Lupo could muster to not let everyone see him cry. He failed.

“The tears were certainly there,” Lupo is telling me a few hours later. “It was a big day for me. It was a big day for everybody standing up there. It’ll be an even bigger day when these structures are occupied by our residents—and that’s what they are. Residents, just like us. Except for unless I was camping, I can’t remember a night I didn’t have an air conditioner or heater. I’ve never woken up with frost on my blanket. We’re all going to be happy that first night when someone doesn’t have to swat off mosquitoes or the first moment morning they don’t have to wake up and shake frost off their blanket. When that person has an address where they can get mail, when they can walk out in the morning and lock their stuff up and come back that afternoon and their possessions are still there.

“That’ll feel better than anything I felt today.”

Birmingham’s “911″ for the unhoused

On any given night there are 943 unhoused residents in Jefferson County, according to Meghan Venable-Thomas, the city’s director of community development, who presented to the council. Of them, 601 are in an emergency shelter (such as the Firehouse) or transitional housing—leaving 342 citizens chronically unhoused. “We’re all one paycheck away,” said Councilor Crystal Smitherman.

For almost 24 years Lupo has been their “911″, their lifeline to life, such as it was. He knows many, many by name, knows their troubled journey, knows their needs. From the basic to the proposed wrap-around services provided by local partners to aid with substance abuse, and mental and physical health issues—a minimum of 75% of our unhoused contends with at least one of these, Venable-Thomas shared.

For almost 24 years, Lupo has been a lifeline for Birmingham’s growing unhoused population.

“To me,” Lupo says, “the wraparound services are all great and wonderful. But there are three things they asked for: “We need a place to put her head down that’s safe. We want a place to be able to lock up our stuff.’ And while they didn’t really say it, it’s in the back of their minds. If you go in an alley or find what you think is a secure place, and you get caught using the bathroom, you’re written up as a sex offender when in fact really what you’re trying to do is use the bathroom.”

There will be one two-stall bathroom for every 10 of the 50 shelters the city will purchase in the pilot portion of the plan. The cost, up to $1 million on Community Development Block Grant funds, was unanimously approved by the council. If the pilot is successful, the city may purchase up to 100 more tiny shelters at the same price. No locations for the villages have been selected, though the thinking is that they’ll be planted across all nine council districts.

“This is not a neatly packaged, wrapped-up silver-bullet solution,” said Councilor Darrell O’Quinn. “But it can be a lasting and positive benefit on people’s lives.”

Seed for a legacy

One day when Lupo was 15, his mother, Billie Rhea Simmons Lupo—a single mom (“She did everything she could to take care of us.”)—told him and his 11-year-old sister Rebecca she wanted to speak with them after dinner.

“I looked at sister and I was like. ‘Okay, what have you done?’,” Lupo recalls with a laugh. “She said, ‘Well, heck, you’re the bad one. What have you done?’ I’m thinking report cards don’t come out for at least another four or five weeks. That can’t be it. What in the world does she want to talk to us about?”

At dinner, “both of us are a nervous wreck because we have no earthly idea what she wants.”

After dinner, she said: “By chance, if something were to happen to me, do you think y’all would be taken care of?”

Don reminded her: “You’ve got a plan for us. Our college educations are taken care of. Everything’s done. But even if it weren’t Memo and big dad [their grandmother and grandfather, would pick us up and carry us up. We’d never miss a beat.”

The teen paused. “I thought, oops, that was the wrong thing to say, so I said, ‘We’d miss you. We’d definitely miss you. But we would be okay.

Six months later their mother was dead. Heart attack.

Lupo later surmised the “divine” reason she’d spoken with them after dinner that night: “She had been affiliated with a group in Decatur called Christ’s Mission. There weren’t a whole lot of homeless people in Decatur, but there were people in need. She wanted to make sure that we were okay if she bought more life insurance and left Christ’s Mission as the beneficiary. She did that. It operated out of a cinderblock building down on Fourth Avenue behind the Decatur shopping center, maybe 40 by 40. It was not a big building for the amount of work they did.

“My mother’s money served as seed money for Christ’s Mission to be able to move into a much bigger place that had a kitchen, showers, everything. And that’s her legacy to my sister and me.”

A legacy that filled Lupo’s eyes with tears as he watched seeds he’s sown for almost 24 years begin to sprout—with tiny homes that could fill big needs.

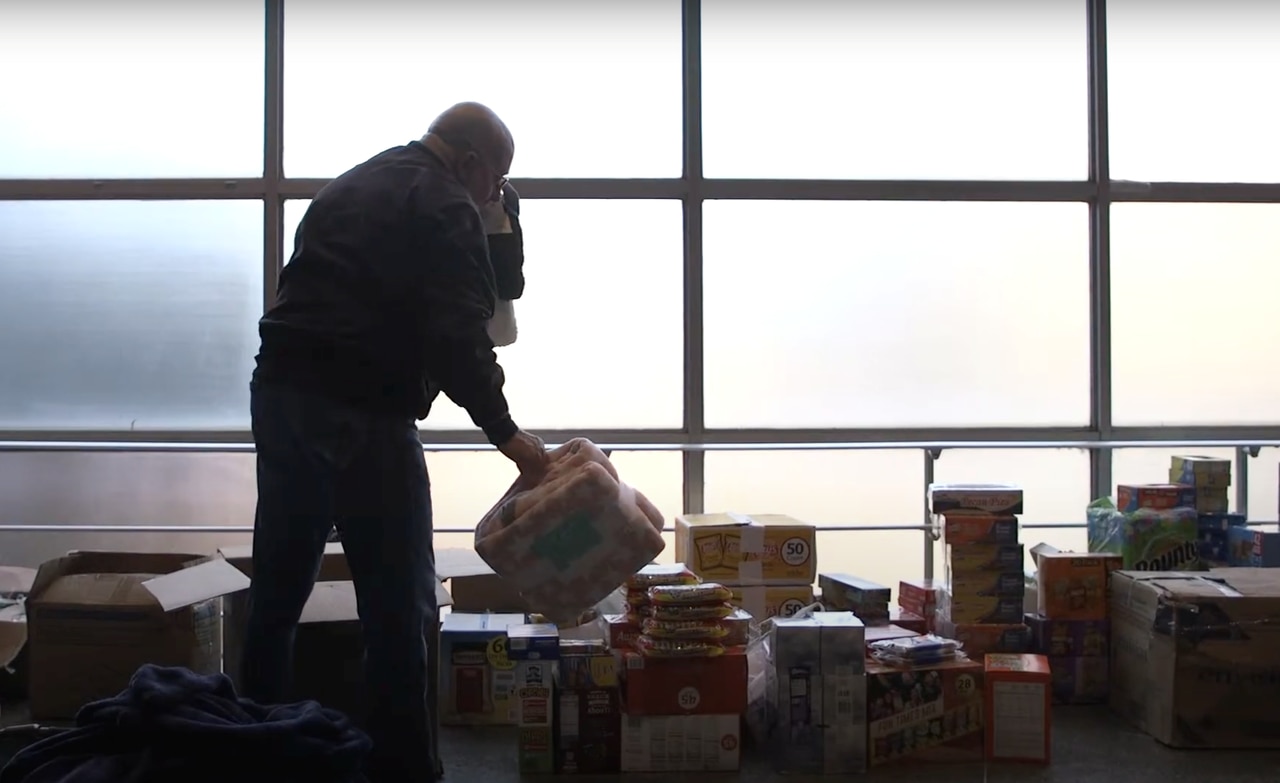

For nearly 24 years, Don Lupo has been a lifeline for Birmingham’s growing unhoused population.

More columns by Roy S. Johnson

Gov. Ivey’s execution moratorium is indeed chance to ‘get it right’, or stop

Think guaranteed-income policy isn’t fair? The Birmingham mom may change your mind

We’re saying goodbye to 2022, but can’t shed its legacy of deadly violence

Though my ancestors are listed on Choctaw rolls, tribe won’t let me belong

Put the brakes on illegal street racing foolishness in our killing streets

We’re tired of being mad, thankfully

Miles grad makes largest alum donation in school history, hopes to be catalyst for giving to HBCUs

Roy S. Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and winner of the Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts: “Unjustifiable”, co-hosted with John Archibald. His column appears in The Birmingham News and AL.com, as well as the Huntsville Times, and Mobile Press-Register. Reach him at [email protected], follow him at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj.