Roy S. Johnson: After Ivey signs fentanyl bill, real work to battle addiction, overdoses remains

This is an opinion column.

A few weeks ago, fentanyl hit me—journalistically, thankfully.

Hardly anyone—anyone outside of the medical, addiction, and first responder circles that confront fentanyl almost daily—was talking about it. Was concerned about it. Was outraged about it.

About the deadliest assassin of our age.

Certainly not as much as homicides, which everyone agrees is a scourge in too many communities. Too many Black communities.

Fentanyl is worse.

Last year, there were 194 homicides in Jefferson County and 446 confirmed drug fatalities (2 remain suspected, pending certification), according to the county coroner’s office. “Fentanyl was responsible for over 80% of the overdoses,” Chief Deputy Coroner Bill Yates told me. “We do not want to lessen by any means a homicide death …But the ripple effects of overdose and drug addiction in our community, which a lot of times end up in death, is huge over many different disciplines and financial budgets.”

“Fentanyl doesn’t have any socioeconomic ideologies, doesn’t care how rich you are, how poor you are, where you live, who your father or mother is,” shared Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr. “If you get your hands on marijuana, methamphetamine, or oxycodone and those drugs are laced with fentanyl, there’s a high degree of likelihood that you would die.”

“It’s crack cocaine in the 1990s,” Birmingham Police Chief Scott Thurmond offered.

Yet fentanyl was a clandestine assassin—to all except those affected by it. A ubiquitous assassin with no concern for race, neighborhood, or status. An often-undetectable assassin that strikes victims who had no idea what they were using—what they were smoking, popping, or injecting—was seasoned with it.

Who had no idea something they’d touched was coated with it. Or that fentanyl floated in the air they just inhaled.

Then they were dead, or close. They were exhibiting the horrific, distinctive signs and sounds of overdosing.

The death growl, as someone I know describes it. Someone who survived an overdose, and who’s saved an ODer.

“When someone died as a result of someone else, whether recklessly or intentionally, it is in the news,” Carr says. “I’ve been talking about fentanyl for three years. Now I think everybody is seeing it manifest, based on the number of overdose deaths we’re having.”

Thankfully.

In mid-March, a collective comprising medical and mental health professionals sounded the alarm in front of Jackson Hospital in Montgomery to launch, “Odds Are Alabama” campaign, an effort to alert people to the risks of fentanyl and direct them to information and help. A U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency study found 60 percent of fake pills it seized contained a potentially deadly dose of fentanyl.

The odds are against us. “Curiosity,” Thurmond said, “can kill you.”

Is killing too many.

Alabama drug overdose deaths more than doubled between August 2016 and August 2022, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths involving fentanyl soared from 453 in 2020 to 1,069 in 2021, according to the 2023 Drug Threat Assessment report from the Gulf Coast High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area Operations Center.

“We got zero to three fentanyl deaths annually prior to 2014,” Yates said, adding: “There used to be a stereotype, but it’s just the facts: Certain drugs were more prevalent in certain racial demographics. So we saw cocaine more in the Black community. We saw methamphetamine more in the white community. Now all the rules are out the door. Fentanyl is being mixed in every product that’s being sold on the street.”

Yates is increasingly concerned about its impact on African Americans, as if our neighborhoods need yet another scourge.

“The biggest problem lately is the increase of overdoses in the Black community,” he said. “From 2019 to 2020 the percentage increases in certain demographics of the black community were just enormous. We had Black females having a two hundred-something percent increase over a year. Black males having a one-hundred-something increase. What we’re told by those who work with addicts and from law enforcement to social workers, and public health people is that the cocaine user in the Black community did not know they were buying a product that had fentanyl in it.”

Sometimes, though did know, Yates said. In fact, they sought product containing fentanyl.

“We would start getting stories from our scene investigation, from law enforcement, or people that were there that the decedent would say, I’m going to go get some of that cocaine that has the fentanyl in it’,” said Yates. “So, we have some evidence now that they are aware it’s in their product and it’s being mixed between groups. I’ve got people in the Black community who died of methamphetamine and fentanyl and people in the white community dying more of cocaine and fentanyl so it’s just all mixed—the drugs on the street. Nobody knows what they’re getting and that’s incredibly dangerous.”

And incredibly frightening—or it should be—for a people already under attack on so many fronts. From within and without.

A couple weeks ago, Morgan Farrington heard loud, wheezing gasps coming from the other side of her bedroom wall….”I thought, that is not snoring,” Farrington said. “That is a death rattle.”

That’s the lead of an enlightening story by my colleague Amy Yurkanin. Farrington is the founder of Goodworks, a Huntsville organization that tries to get ahead of the plague through what’s called harm reduction—providing those most at risk with safe tools and spaces for using drugs.

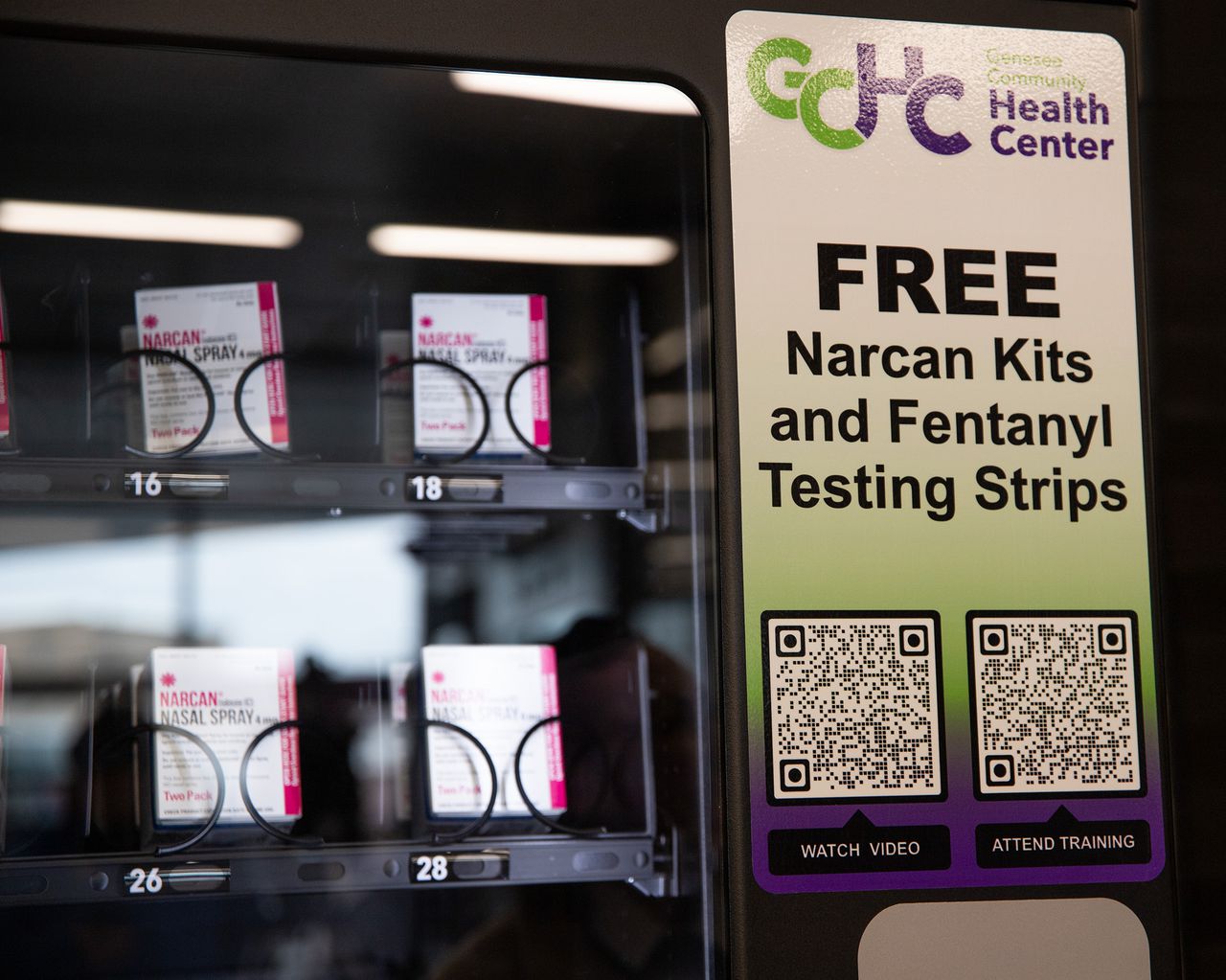

She, and others like her need. Help. They need to be seen and embraced as vital to the strategies needed to stem addiction, support those wrestling with it, and ensure Narcan, a life-saving inhaler that can stem an overdose, is as accessible as condoms.

From Carr: “If you didn’t have Narcan available, which many people don’t, then you will probably overdose, and your life will not be spared. That’s reality.”

Alabama lawmakers are fast-tracking a bill to apply mandatory minimum sentencing for anyone caught distributing more than a gram of fentanyl. That would apply to anyone who sells, manufactures, delivers, brings into the state, or knowingly possesses one gram or more of fentanyl is guilty of trafficking.

It passed the House on Friday with a rare 105-0 vote. Not long after you read this, it could be law.

With our prisons already overcrowded and unconstitutionally inhuman, mandatory sentencing seems moronic. Yet the argument put forth by the bill’s sponsor, Rep Matt Simpson, R-Daphne, is that other drug trafficking crimes have mandatory minimum sentences when fentanyl does not.

I get it, and I’ve got no issue with the bill. However, it must only be a start. Truth is, identifying the source of the assassin drug is frustratingly difficult. “It will be hard to trace the source of the drug back to an individual,” Carr says. “You get marijuana from someone, that marijuana could’ve come from anybody. You get a pill it could have come from anybody.

“I do think people need to know that if they supply a drug laced with fentanyl and they knowingly supply a drug laced with fentanyl and someone dies as a result, they can even be charged with manslaughter, which is a homicide. I think that’s big for the community to know.”

After lawmakers pat themselves on the back for their law-and-order stance, they must sit down and do the real work required to better combat addiction, to provide more resources to people and programs out in these streets trying to prevent fentanyl deaths.

Before fentanyl hits them, too.

More columns by Roy S. Johnson

Woke is the far right’s sky is falling; it fell on them

I’d like to thank my teachers, too, and this coach

Gov. Ivey’s legacy: Prisons? Medicaid? Her choice

Alabama Republican’s ‘parents’ rights’ bill smells like ‘states’ rights’; I’m holding my nose

Early release of the 369 is the most compassionate, smartest thing Alabama prisons have ever done.

Roy S. Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and winner of the Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts: “Unjustifiable,” co-hosted with John Archibald. His column appears in AL.com, as well as the Lede. Subscribe to his free weekly newsletter, The Barbershop, here. Reach him at [email protected], follow him at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj