Regrets, and memories of some powerful lessons

It was the early 1970s, when I was still a teenager, and my father had just hung up the telephone, after which he proceeded to tell us that a long-time friend of his had died. This came just a few months after Daddy had gotten a call from a relative who reported the death of his cousin-in-law, also a long-time friend.

Taking a drag from his cigarette and a sip of his bourbon-and-7UP, he turned philosophical.

“That’s the thing about making it into your 50s,” he said. “Suddenly, death isn’t as abstract as it once was. You look up, and this friend or that cousin is dead. Somebody you played with as a little boy. You and he and the rest of your gang were going to grow old together.”

He added his theory that if you could make it through your 50s without contracting a fatal disease or dropping dead from a heart attack, you’d sail into old age with little or no trouble.

Alas, he did not get the chance to look back from his 60s, 70s or 80s and say, “Told you.” Daddy died of cancer a few years later, at the age of 58.

I’m thinking of him now as I process the news of the death of the man who gave me my first newspaper job in Alabama, as a reporter at The Foley Onlooker. The Onlooker was published twice a week and paid significantly less than the small daily papers in Texas and Louisiana where I had previously worked.

But I wasn’t complaining. After having spent six months as a Kelly Girl, I was thrilled to have a job again in my field. The publisher, whose name was Charles Beasley, was thrilled, too, having just had someone quit abruptly. At a small-town newspaper, one person leaving can create a big hole in the staff.

So we were a match made in heaven, he and I. We were friends at work, and with our spouses were also friends socially. We worked together for about five years, during which time he promoted me to editor. Eventually, though, he segued into a successful career with an insurance company and I moved on to the daily newspaper in nearby Mobile, Ala.

Though I am now 70 and Charles was 75 when he died, when I heard the news, I felt what I think my father must’ve felt when he got those long-ago phone calls: Wait. This wasn’t supposed to happen. We were going to keep on sailing, at least into our 80s and maybe longer, and remembering the good times we had as colleagues and friends.

Death is the ultimate trickster, however. You don’t necessarily realize it while you’re young, but it begins to dawn on you as you approach middle age. When you’ve reached my age, you’ve acquired plenty of evidence that none of us knows when the Grim Reaper will call on friends, family members and one’s self.

I have some regrets, of course — the main one being that I didn’t keep in regular contact with Charles and his family. But I also have some important lessons I learned from him.

For starters, I saw up-close-and-personal that while journalism is a noble thing, somebody (at The Onlooker, it was the publisher) must run the business side and produce enough income to keep the lights on.

At big papers, people in the news and advertising departments don’t know or care much about what the other department does. At little newspapers in small buildings, where all of you work cheek-by-jowl, you don’t have the luxury of being a snotty, self-important reporter who’s convinced that the pretty sales reps sell a few ads in the morning and then sit around and paint their fingernails for the rest of the day. With strong leadership, you understand that whether the newspaper succeeds or fails depends on all of you working as one. Charles was that kind of leader.

The second and more important lesson he taught me was how to be a boss. Charles listened to his staff’s concerns and he had our backs, whether it was the sales reps complaining that the news side had offended their customers, or reporters complaining that ad sales shouldn’t influence news coverage, or local civic and political leaders complaining that our reporters asked too many hard questions and printed too many of their wishy-washy answers.

Later, at the daily paper in Mobile, where I oversaw the opinion pages, I used those lessons to keep my department on an even keel, even amid monumental changes in the newspaper industry.

Over the years, I’ve used relied on Facebook to keep up with his family, including birthdays, weddings and grandchildren. It’s a great tool for that.

Its drawback is that Facebook and other social media can create an illusion that you’re staying in touch with someone when, in truth, you’re not. “In touch” should mean phone calls, occasional visits or, at minimum, periodic texts or emails. I regret that I didn’t do any of that.

Even so, I know a fine man when I see one, and Charles was a fine man. As his family and friends sail on without him, it’s a memory worth cherishing.

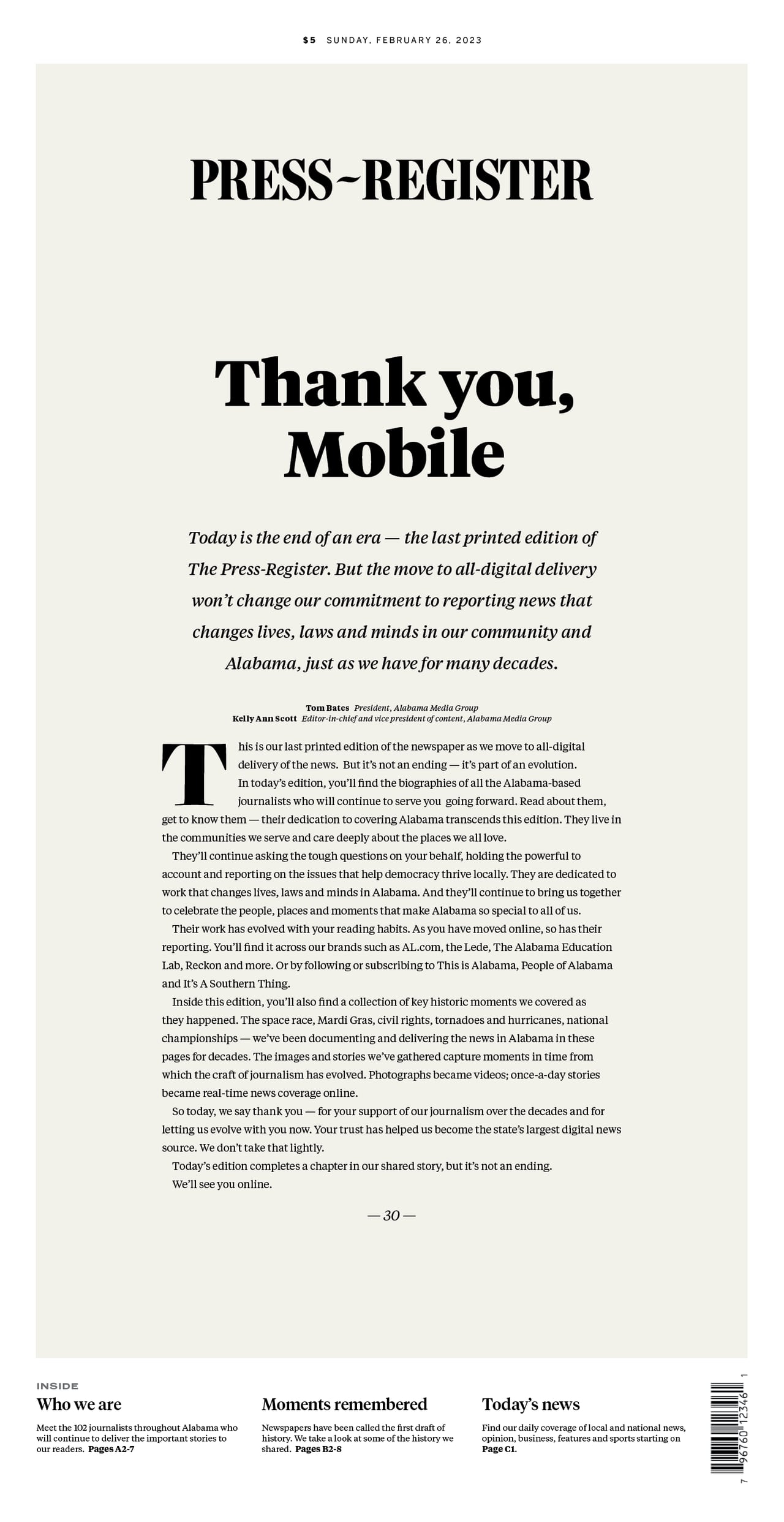

Frances Coleman is a former editorial page editor of the Mobile Press-Register. Email her at [email protected] and “like” her on Facebook at www.facebook.com/prfrances.