Q&A with Jeff Pearlman on his new Bo Jackson book

Jeff Pearlman has written best-selling biographies about many of the more celebrated and controversial sports figures of the last half-century, from Walter Payton to Roger Clemens to Magic Johnson and the “Showtime” Lakers.

Pearlman’s books typically leave no anecdote unexplored, digging deep not only into the big moments and games from an athlete’s career, but also the incidents and experiences both large and small that helped shape them as a person. His latest book on Auburn legend Bo Jackson, for which he conducted more than 700 interviews, is no exception.

Due out Tuesday from Mariner Books, a subsidiary of HarperCollins, “The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” tells the story of Jackson’s humble roots in Bessemer and at McAdory High School to stardom at Auburn to near-mythical figure who excelled in professional baseball and football simultaneously and was among the more successful advertising pitch men of the modern era before a 1991 hip injury cut short his career. An award-winning writer for Sports Illustrated before turning full-time author, Pearlman interviewed hundreds of Jackson’s friends, coaches, teammates and opponents from various points in his life for the 400-plus-page book, which is a wildly entertaining and insightful read.

NOTE: Pearlman has four book signings scheduled around the state in the coming DAYS: Friday (5:30 p.m.) at Auburn Oil Booksellers in Auburn; Oct. 31 (7 p.m.) at The Little Professor in Homewood; Nov. 1 (7 p.m.) at Downtown Books in Dothan; and Nov. 2 (6 p.m.) at Page & Palette in Fairhope.

Pearlman spoke with AL.com for this Q&A last week. The following is a partial transcript of that interview, which has been condensed for length and slightly edited for clarity:

Author Jeff Pearlman, author of 10 best-selling sports biographies including “The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” which was published Tuesday, Oct. 25, 2022, by Mariner Books, a subsidiary of HarperCollins. (Photo by Michelle Nicoloff via HarperCollins)

Q: What drew you to wanting to tell this story? What do you think is Bo Jackson’s legacy as an athletic and cultural figure?

A: “I think he’s the greatest athlete who’s ever walked the planet. I really do. And I know, obviously, I can’t prove it. I’ve never seen him compete against Jim Thorpe, for example. But if you look at the collection of his work starting in high school and you look at a kid who, when he was at McAdory, was a two-time state decathlon champion who as a senior in high school won the decathlon on a half sprained ankle. And the next day pitched a complete game, struck out 13 hitters, in a state playoff game. It’s preposterous. It’s utterly preposterous.

“There’s no ‘secret timing’ to the book. People ask, ‘why’d you write it now?’ And it’s like, I wrote it now because I wanted to write the book. I just hate the idea of people not remembering him. And as time passes — I don’t think my kids’ generations are very well-versed in Bo Jackson. And I think they should be. I think he’s an all-time historic figure of sports. I think he’s a marvel of the world. I’m all about Bo Jackson, people remembering Bo Jackson.”

Jeff Pearlman’s “The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson” was published Tuesday, Oct. 25, 2022, by Mariner Books, a subsidiary of HarperCollins. (Book jacket photo courtesy of HarperCollins)

Q: Along those lines, most people recall the big moments — the All-Star Game home run in 1989, the Monday Night Football game in 1987, running up the outfield wall in 1990, all of that. But in your book, there’s a lot of incredible high school track and field, baseball, college baseball stories. How hard was it to separate fact from fiction with all that stuff, so it’s not just a collection of tall tales?

A: “Oh, incredibly hard. And I feel like I almost could have put a disclaimer in this book saying, ‘Bo Jackson is Paul Bunyan.’ Everything here was fact-checked and verified as much as possible. But you are relying on memory. So when some kid recalls a home run going 500 feet, and I say, ‘really 500 feet?’ and they say, ‘I’m telling you, we walked out to the street after we found the spot where the ball went’, that kind of thing, I’m a little more willing to take their word for it than I would be with other figures. I feel like there’s almost like a ‘wink, wink, nudge, nudge’ to a lot of like the Bo Jackson stories. The reason (the book is) called, ‘The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson’ is because there is a lot of mythology to him. Nowadays, all this stuff would be captured on Instagram and TikTok and there’d be a million videos — ‘McAdory high school kid hits ball over the train tracks.’ And it would be everywhere. And it would go viral. But that didn’t happen then. So you are relying on the stories in the folklore. And I’m kind of comfortable with that, to be honest with you.”

Q: A lot of what has been written about Bo Jackson or even documentaries about him, focus on ‘look at all these incredible things he did.’ And obviously you have all of that in the book, but you also tried to get at Bo Jackson the person. Do you think you were effective in that?

A: “I’d like to think so. He a weird guy. And I think weird is accurate. I get you get that a lot from people, who will be like, ‘Yeah, he’s a weird guy’ and it’s not weird in a negative way. He’s just quirky and he’s guarded and he’s off-putting and he doesn’t love … he’s not mushy and embraceable in the way a Walter Payton was. He doesn’t want you coming up and asking for an autograph during meals. I mean, there there were guys on the Raiders who were terrified of asking him for an autograph of anything or even going up and approaching him. There were guys on the Royals who were like, ‘he was not approachable. I could not go up to him.’

“He was a guy, when he was with the Royals, he’s shooting bow and arrows through the locker room, through the clubhouse. And he was able to do that because no one had the guts to go out to him and tell him not to. People were just afraid of him. He beat the living hell out of Kevin Seitzer when they were Royals teammates. And really no one could say anything to him. No one could say anything to him about it. He couldn’t get suspended or fined because people were afraid of him. And it wasn’t like he was a bad guy. He was a good guy, but he was a brooding guy and he was hard to read. Very mysterious. Definitely a mysterious human.”

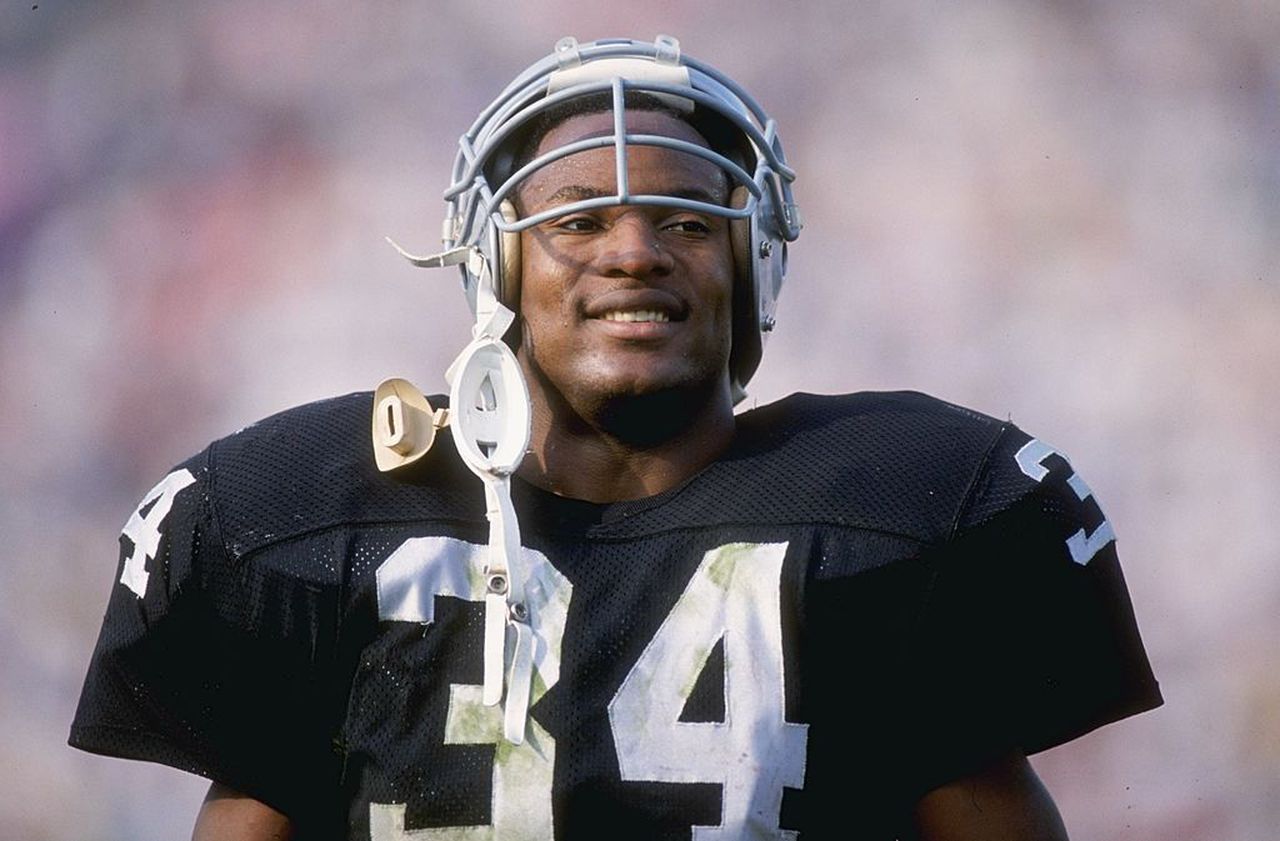

Los Angeles Raiders running back Bo Jackson at an NFL game against the Phoenix Cardinals on Dec. 10, 1989.Mike Powell /Allsport

Q: My theory about Bo Jackson is that he doesn’t care if he’s liked, but he wants you to be in awe of him. Do you agree with that?

A: “That is so perfectly said. I’m going to have to steal that [laughs]. … I think most athletes do care what you think, even if they act like they don’t. But Bo Jackson is totally devoid of that. I do I think being the greatest athlete of all time matters to him. I just think he doesn’t want you to think it matters to him. … He can be a real dick in certain situations, but then he goes and pays for the funerals of all the Uvalde (school shooting) victims. There’s a real, beating human heart in there.”

Q: You’ve written about Roger Clemens and John Rocker and Brett Favre and other sports figures who are not particularly well-liked as people. Did you find that you liked Bo more or less now than when you started?

A: “I would say more. I’ve been having this discussion a lot with friends. There’s something admirable in being able to leave your life behind, your past athletic glory behind. And for the most part, he has. … Maybe he really wants you to talk about him, but he’s trying to make it look like he doesn’t. You never hear him complaining about his fate. You never hear him saying ‘Terrell Davis [whose career was also cut short by injury] got into pro Football Hall of Fame. You can make a case for me, too.’ Never ever, ever. You don’t see him on TV broadcasts. He’s not hawking ‘Bo Knows’ steaks. He’s lived a pretty dignified, out-of-the-spotlight life. He shovels his own driveway. He drives a Ford truck. He hunts, he fishes. He left the spotlight. And I think that’s really hard and I think it’s really impressive. And he runs a really cool charity, Bo Bikes Bama. I do think, overall, he happens to be a pretty exemplary guy.”

Bo Jackson won the Heisman Trophy at Auburn in 1985. (Photo by Focus on Sport via Getty Images)Focus on Sport via Getty Images

Q: He’s talked a lot about how he was a bad kid, but some of the stories in your book about killing pigs and some of the things about his personal life at Auburn are not really positive to his repuation. Did you have any qualms about reporting all that kind of stuff? Or is it just part of the full picture?

A: “A lot of it was taking his autobiography [1990′s ‘Bo Knows Bo’] and dissecting it. It was taking his book and breaking it down. In his book, he tells a little bit about the time they beat up the boar hog. Well, I go to Bessemer and I’m like, ‘I want to find out where this happened.’ And I go to the farm where it happened or the land where it happened. And the same family doesn’t own it anymore. The farmer’s dead. But I track down his son and his son told me all about his dad and the farm and the animals and what they owned and so on.

“His autography actually gave me a lot of joy as a kid. I think it’s a good sports autobiography, but it comes from the very narrow perspective of someone telling you information they want to tell you. And I think my job — part of my job — is to go and take something and then dissect it and break it down and break it down to another layer and another layer and another layer. Bo mentioned a barber. I found out who the barber was. He’s dead. But you throw out a name and you find out who this guy is and what he was like at Auburn. He was a pain in the ass. There was no doubt about it. He hated practice. He didn’t want to practice hard, he didn’t need to because he was so much better than everyone. … But it’s not an indictment, that’s the thing. He was 19 years old, 20 years old. If you did a book about me at 19 years old, you’d find a lot of things that were annoying too. You’re just a kid. So I don’t view it as a negative, I really don’t. I just think it is what it is, who he was, you know?”

Q: You mentioned ‘Bo Knows Bo,’ but you were able to get hold of the original interview tapes with (author) Dick Schaap. How much of a treasure trove was that for you?

“It’s maybe one of the greatest discoveries of my career. Someone at Auburn said ‘I think Dick Schaap donated his notes to the Auburn library’ and I thought, ‘Whoa. Really?’ It took me a little while, but it turns out that he did. I had to pay for it, a couple hundred bucks. And they sent me all the audio recordings from their interview sessions together. So hours and hours and hours of audio recordings, all the transcripts printed out, plus a bunch of other notes. Written notes on paper about different things, observations. Bo didn’t talk for (Pearlman’s) book. But I really felt in a way, like I was having conversations with 28-year-old Bo Jackson. And a lot of the material was never used in the book. Some of it was because Bo didn’t want it out there and some of it was just overlooked. And it was gold. It was absolutely gold.”

Q: I’m fascinated that you were able to track down some of these people, like the one catcher who threw him out stealing in high school. I’m sure that social media helps a lot, but how involved a process was that’s sort of thing? How many steps did you have to go through before you get to the right person?

A: “His name was Sam Doss from Jess Lanier. First you find out that Bo Jackson stole 90 of 91 bases in high school. And I guess your first reaction is ‘holy shit.’ But then your second reaction has to be, ‘I wonder who the one guy was who threw him out.’ So you start interviewing people from high school opponents. You start interviewing high school opponents and high school teammates. And someone at one point said, ‘you know I know the guy who threw him out.’ And I got a number and called Sam Doss and he was awesome. … And he vividly remembered throwing Bo Jackson out.”

Bo Jackson walked the Tiger Walk before the Iron Bowl NCAA college football game against Alabama, Saturday, Nov. 25, 2017, in Auburn, Alabama.(AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Q: One of the fascinating turns is when he gets drafted by the Yankees (out of high school) and he basically ghosts them to go to Auburn. Is that ‘I promised my mom I’m going to college’ or because ‘somebody in the Auburn booster family’s taking care of me and I don’t need the money’?

“I think it’s a little bit of both to be honest with you. Definitely, Auburn was putting every blockade up imaginable. They literally had people sitting next to Bo Jackson’s mom at high school baseball games to keep people at bay. At the same time, his mom did really want him to go to college. He would’ve been the first — he had a brother who went to community college, but otherwise he would’ve been the first from that family to go to a four-year college. It was important to her; she worked her ass off. But it’s funny because this poor scout for the Yankees, Gus Poulos, they draft him in the second round. They know they have something special. He was watching Bo Jackson all the time. He said ‘this guy is the best player in overall ability in my 21 years of scouting.’ On the day of the draft, the Yankees call Jackson’s household. No one answers the phone. They call the next day, no one answers the phone. They reach out to the high school coach. ‘Can you call Bo?’ ‘Yeah, I’ll call him.’

“The team says they want to fly Bo and his coach to New York to watch Yankees play the Red Sox. You’re a kid in Alabama, right? You’ve left the state one time in your life to go to Georgia. … There’s no catch here. You don’t have to sign with them, they just want to fly you to New York City to go watch Yankees play the Red Sox. Nine hundred ninety-nine out of a thousand kids say yes. There’s no logical reason on the planet not to go to, even if you’re committed to Auburn. … He didn’t do it. He wouldn’t do it. He didn’t give a shit. He didn’t even know the Yankees and Red Sox were rivals. He didn’t know anyone on the Yankees except Reggie Jackson. Just like when he got his first major-league hit against (future Hall-of-Famer) Steve Carlton, he didn’t know who he was. I love that stuff.”

Q: Bo came out on Twitter not long ago and accused you of trying to make money off his story. You mention in the book that you reached out to him several times and while he wouldn’t agree to an interview, he also didn’t try to stop you from writing the book. Does that bother you that he apparently changed his mind?

A: “I’m happy you’re asking this question. … The thing that really bothers me about this is, besides the fact that I went out on my way to talk to him, is that this book is 98% a love letter to Bo Jackson. It might sound dumb, but I really want people to remember how freaking great this guy was and how otherworldly he was. My kids don’t have a clue about Bo Jackson. They do because I wrote a book, but they wouldn’t know Bo Jackson. Their friends wouldn’t know Bo Jackson. It’s important to me.

“And the thing that bothers me when people say this is … for example, do we only allow Donald Trump to write a book about Donald Trump? Do we only allow Obama to write a book about Obama? So no historians are allowed to write books about these people? The only people who can write books are the people themselves? Our sense of history would be so warped and so decimated. It would be shameful for this country and for society and just for understanding of who people are. It’s preposterous, the idea that the only one who can tell a story is the person himself from his vantage point. It doesn’t make any sense. From JFK to Marilyn Monroe to Joe DiMaggio to Vince Lombardi to whoever — take the great biographies out there, take the hundred greatest biographies out there and they’re better than the best autobiography. They just are. Because they’re more researched and they’re more nuanced. I didn’t come into Bo Jackson with any bias whatsoever. if anything, it was a bias of loving this guy as a kid.

“And if Bo Jackson writes his own book, he’s not researching, he’s going off of memories from 30 years ago. They’re skewed memories. His own autobiography, he doesn’t mention one iota about boosters at Auburn. And I don’t blame him, but he doesn’t. He doesn’t mention (the death of Auburn teammate) Greg Pratt. He doesn’t mention his college girlfriend that he doesn’t marry, that had a fiancée before his wife. He doesn’t go deep into the hardships of his stutter. Biographies are necessary. They just are.”

Creg Stephenson is a sports writer for AL.com. He has covered college football for a variety of publications since 1994. Contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter at @CregStephenson.