Professor recalls growing up in Birmingham public housing called âpoorest ZIP code in Americaâ

Jerome E. Morris, a professor of urban education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, grew up in downtown Birmingham’s subsidized housing community known as Central City.

In the 1980s, Central City was renovated and renamed Metropolitan Gardens. In 1999, it was demolished and gradually replaced with a Hope VI mixed-income community called Park Place with fewer subsidized apartments.

“Americans have given up on public housing,” Morris said. “There’s this whole move away from the public good.”

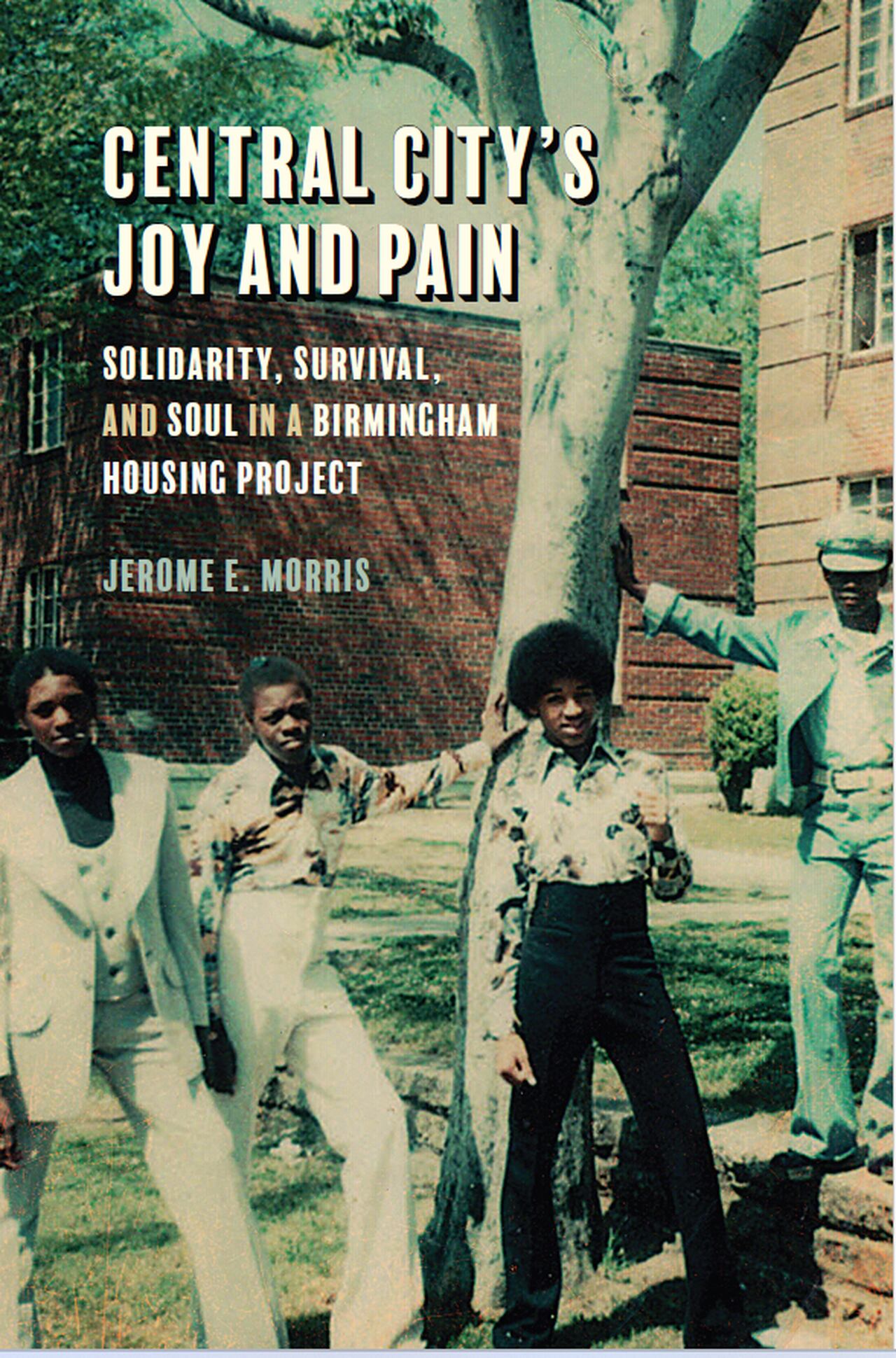

In a new book published in January this year, Morris tells his own personal story of growing up in poverty and how he overcame it.

The book, “Central City’s Joy and Pain,” published by the University of Georgia Press, features Morris’ sociological insight on urban life, but the core narrative is that of his own life and his family’s struggles.

“Nobody else is writing this story,” Morris said.

The dust flies as a power shovel is used to remove debris from a building of the former Metropolitan Gardens housing project as the sun shines over downtown Birmingham. News Staff Photo Mark Almond bn

Morris lived in Central City from 1968 through 1991, and he interviewed 40 other former residents of Central City and Metropolitan Gardens for the book.

“I blend social science research and historical with my own personal experience,” Morris said in a recent phone interview. “It’s a study of displacement from Metropolitan Gardens.”

Morris looks back on his childhood in Central City with fondness and nostalgia, despite frank admissions about the troubled life of his family.

In the book, Morris recalls his vivid memory of going with his mother to a nearby social club, where the female owner gave him a free bag of onion rings just before accusing his mother of bragging about sleeping with her man, then pulling out a pistol and clubbing his mother on the head. Morris’ own shirt was bloody as he stood over his mother while an ambulance picked her up and took her to a hospital.

Morris tries to take a broad view of where he grew up.

“It’s really connected to issues around urban planning and housing, what role do Birmingham’s Black poor play in Birmingham,” Morris said.

Morris, 55, was born in 1968, the same year the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and the Fair Housing Act was passed, allowing his mother to move her children into Central City housing community.

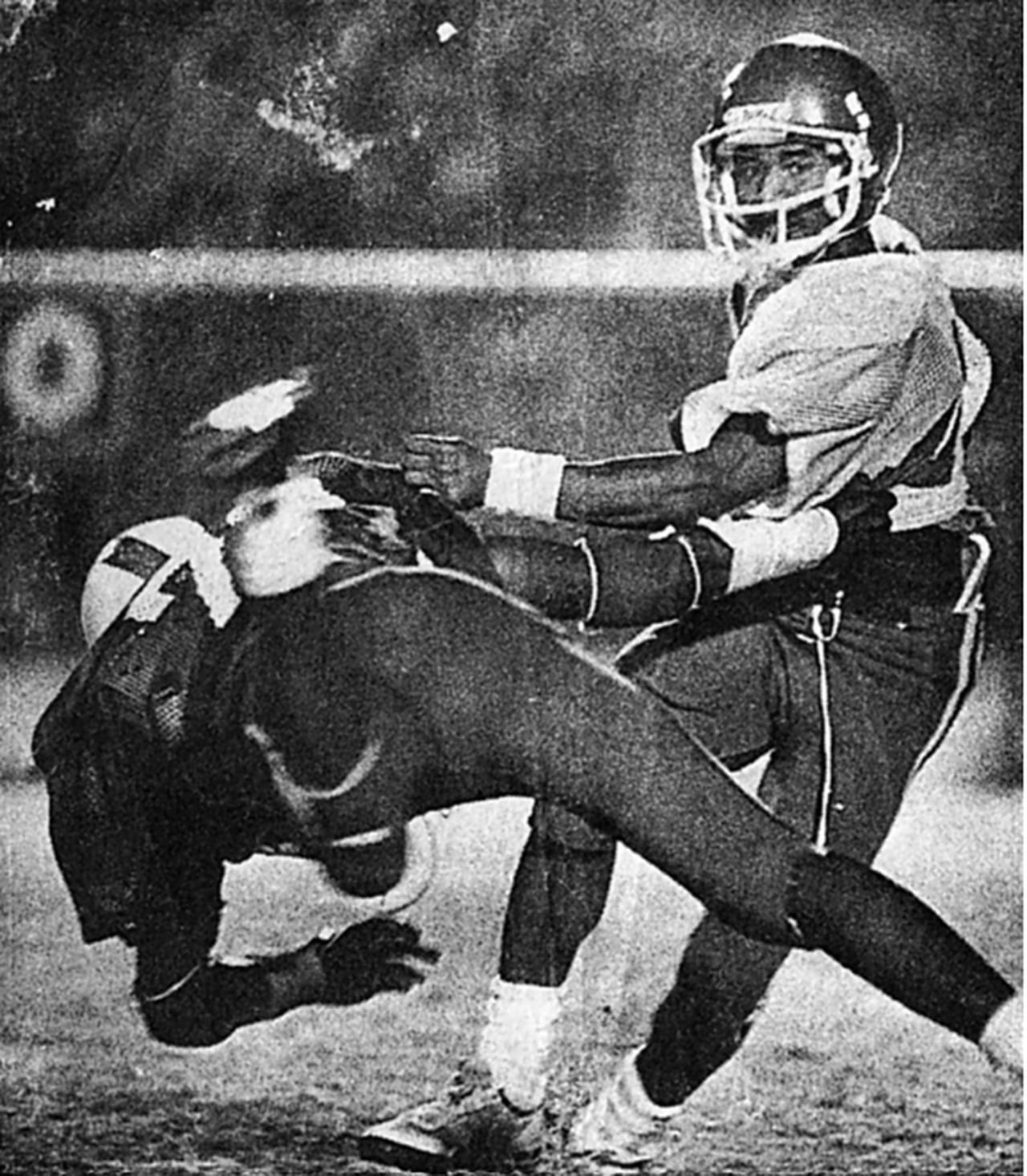

Morris walked to school at Powell Elementary, and then to Phillips High School, where he was student government president and became the starting quarterback on the football team and eventually earned a scholarship to Austin Peay University before earning a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt University.

He taught 18 years at the University of Georgia before accepting an endowed professorship in St. Louis in 2015.

Jerome E. Morris graduated from Phillips High School in 1986, where he played quarterback for the high school football team. (Birmingham News photo/Bernard Troncale)The Birmingham News/File

Central City was built for poor white people in 1941 and Morris’ family was one of the first Black families to move in after the Fair Housing Act. As more Black families moved in during the 1970s, white families moved out. “The white people didn’t last long,” Morris said.

During his childhood, Central City became known as “the poorest ZIP code in America,” a place known for poverty and violence that was hard to escape.

“There’s this concentrated poverty,” Morris said.

“There are brilliant people, smarter than I was, who don’t come out of there,” he said. “I want them to see how their lives have been shaped by overarching forces. Some people have 20 options. You got two. You make a bad one, it’s through.”

Yet, interspersed with the pain, Morris carries away positive, nostalgic memories of extended family.

“There’s pain,” Morris said. “Human beings still live their lives. They have children. They love each other.”

Growing up, he had a sense of community, even with its flaws, he said.

“The key thing is stability,” Morris said. “Central City was a stable place for residents, families. There was a stability, walking one block to school.”

He feels the poor have been squeezed by housing policies that lead to even more violence and broken dreams.

“It’s very chaotic in Birmingham,” Morris said. “Some of what you’re seeing today is a byproduct of displacement of Black families.”

He knows it first-hand from his family’s experience being forced out of Central City and moved to Tuxedo Court in Ensley, then known as “the Brickyard” to its residents.

“My mother moved in 1999, moved into the Brickyard,” Morris said.

“She was depressed from that. All hell breaks loose. She died two years later. My mother was 58 years old. She knows nobody in the brickyard. It was horrible. The loneliness people have, they’re disconnected. My sister struggled, was on drugs. My family is a microcosm of what happened.”

Tuxedo Court, built in the 1950s with 488 units, was vacated in 2005, demolished starting in 2006 and replaced with the Hope VI development Tuxedo Terrace, with 331 mixed-income units.

Hope VI is a $5 billion federal program started in 1992 that offers local housing authorities cash grants to replace their worst public housing communities. The program tries to create mixed-income communities that include some subsidized and some market-price properties.

Morris sees the forced migrations happening again with the start of demolition in 2021 of the Southtown Court public housing community between UAB and St. Vincent’s Hospital.

The same will happen with the planned redevelopment of Smithfield Court, he said.

Residents will be forced to move, told they have a chance to return, then there won’t be a place for most of them, Morris said.

“I know there is a better way,” Morris said. “The better way is the eradication of poverty and fostering community. How does this society create ways of eradicating poverty, disproportionally Black poverty, and find ways of creating community and quality education?”

In the older public housing communities, “you’re affirmed, and people treat you like family,” Morris said. “A child should not go to a school where people don’t like them.”

During its height, Central City housed 910 families in one-story, two-story and three-story buildings.

“You know how many Park Place has?” Morris said. “It has 700 housing units, 47 reserved for low-income families. The vast majority were market rate.”

His mother was so convinced that she would be able to return to Central City when it became Park Place that she asked Morris, then a student at Vanderbilt, to pay for a door that the Housing Authority charged her $100 for because it was damaged, even though the entire building was scheduled for demolition a month later.

The newer housing developments are not about housing the poor, but making profits for developers, Morris asserts.

“There is no war on poverty in America,” he said. “America has made peace with poverty. They rationalize it. Those are smokescreens. Those are things to get people money.”

Jerome E. Morris wrote a book called “Central City’s Joy and Pain,” published in January 2024 by the University of Georgia Press. The cover photo features his brother, Richard Lee Morris Jr., in dark pants, with some of his friends in Central City. University of Georgia Press