Poetry as an archive for generational healing with Tatiana Johnson-Boria

Poetry has long been used as a form of self-expression by both serious and non-serious writers. As a child, before I knew what poetry was, I was writing poems. I was searching for words to describe what I was feeling and experiencing. I was allowing the page to hold what I was maybe too young to carry. Poetry can function as so many things, but maybe its most meaningful function is to document, affirm and heal our inner wounds.

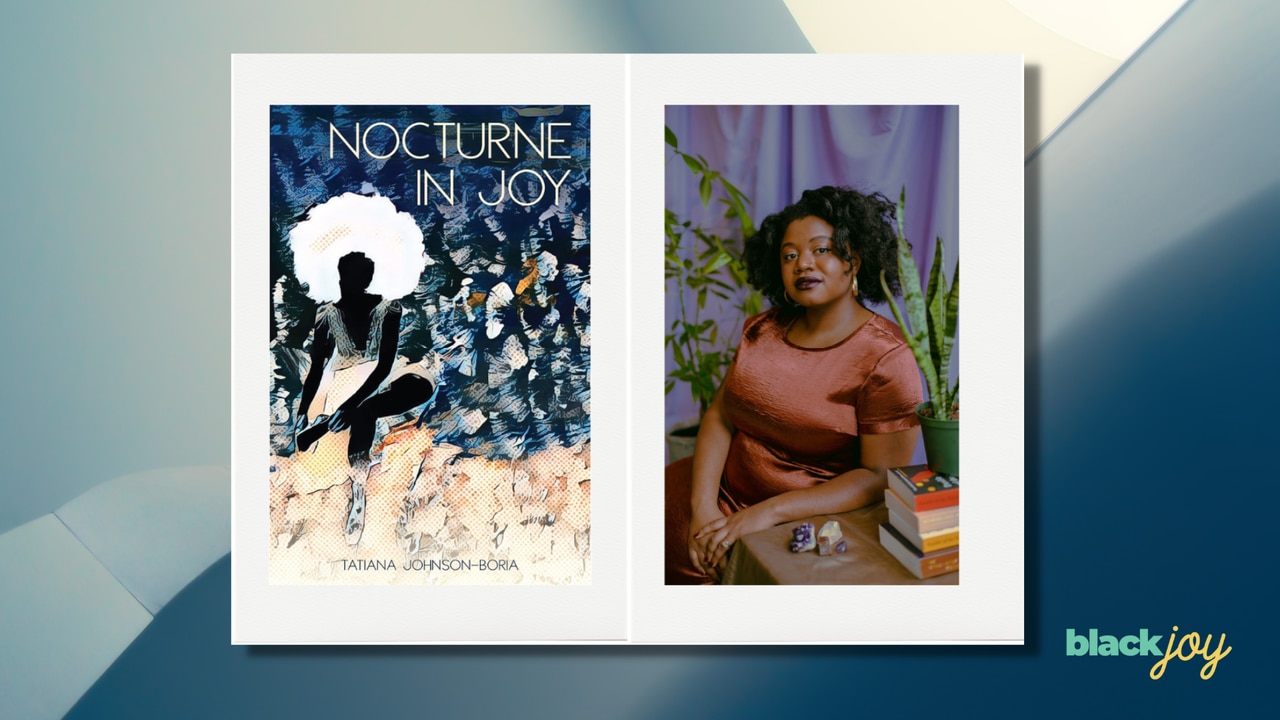

Author and educator, Tatiana Johnson-Boria, gives us a master class in using poetry as an archive and a mode of healing. In her latest poetry collection, Nocturne in Joy, Boria paints a picture of how intergenerational trauma manifests in Black families and what it means for Black children to bear witness to and suffer on account of familial trauma. Despite its heavy themes, she finds a way to weave in the joy that is inherent to the ways Black folks have survived in this country. In my conversation with her, we discussed all that and more.

The storytelling in this collection is really vivid and beautiful. And as a reader, I feel like I’m here with the speaker. And it also feels like a familial archive, documenting all that has been inherited from generation to generation. Can you talk a little bit about poetry as an archival practice?

I feel like poetry as a tradition is also an oral tradition, it has roots in song, music, storytelling—I actually was just listening to a podcast this week with Adrienne Marie Brown, and she was saying, we sing to tell stories to survive. And I think of poetry as something similar in its way of telling poems or writing poems to survive in the same way I think song has been used throughout decades and time.

So, I think inherent to the form or to the practice or the art is some kind of storytelling and witnessing to just say, “This has happened. Do you see me? Do we connect?” and building connections through that.

Two really strong figures in the collection were the maternal and the paternal figure. Can you talk about that dichotomy or what they represent to the speaker in their journey towards generational healing?

With this question I’m thinking a lot about two of my favorite poems from the collection: “My Father Hums in the Kitchen and for the First Time This is Art” and “Portrait of a Mother Before Sunrise.”

So, I think for me, going back to the archive question, a lot of this comes from my personal life and my family’s history and I was thinking about just generations of my family, a few generations back and what I’ve been able to find in research and seeing the same archetype being repeated over and over. Maybe a family situation where there’s violence or where there’s trauma that has happened or transpired in the family and I was thinking about how that had played out in my family between the matriarch and patriarchs.

It was so interesting to me because it’s on my mother’s side. It’s on my father’s side. All of those lineages of the same story, and the sequence poem that is spread across many pages, Nocturne in Joy, kind of chronicles a bunch of different things about the family. I was trying to think about it in sort of a Greek myth type of way where it’s these archetypal figures and how they’re these gods, and they’ve been played out over and over again in different lives. And so, I think that’s what I was thinking about with those figures, although they’re specific to me, I see them as really archetypes for the various generations in my family and in others.

So, I wanted to paint them with some specificity with “My Father Hums in the Kitchen” and the portrait poem in these specific moments of their humanity as people, but also within that same context of them being these archetypes of, contributors of maybe harm or neglect, [but also] figures who’ve experienced deep harm and pain in their own lives. So, I think that’s what those two poems are doing. And I think the “my father hums” poem was also a moment of trying to reckon with moments of gentleness, moments of real fear or anxiety. I think those were the crux of those pieces.

Another thing that came up was Black children bearing witness even as they’re often rendered invisible in families. And so, I think people don’t consider what they’re taking in and how it affects them. I pulled the following lines to reference.

That reminded me of how we become adults with a wounded inner child. So, how do we work towards healing our inner child while also holding space for generational traumas that often cause cycles of violence that plague our ancestral lineage?

I think something I’m still reckoning with, just personally and also just thinking about my family—I recently became a mom, too. And so, I think I was thinking about the ways in which children are in such a vulnerable state because they can’t really advocate for themselves. But they’re also, as you said, a witness to so much and probably in a more observant way than adults. They see things that I don’t think adults are even able to see about themselves. And so, I was thinking about that specifically with that line that you read, about the responsibility or the burden or the weight that comes with seeing things [from the] perspective of a child.

You were asking about healing the inner child or how to move towards that space. And I think visiting those moments both emotionally and intellectually, and kind of reclaiming them or revising them in a way. The EMDR section [in the collection] is kind of about that. EMDR in that practice of psychotherapy asks you to revisit these moments and see yourself there like your present self there with your past self. And I think being able to reimagine those moments is one way of healing that inner child.

What if I reimagine my present self being there? And what if I reimagine myself carrying my inner child, physically lifting them up. So, in a way, it’s kind of creating some new world for yourself to live in because I mean, it’s a pretty incredible thing to do that. In that reimagining there’s a potential for healing because I think in a lot of those moments, at least for me personally, it’s the feeling alone or feeling unseen that I think has created such a severing. And I think seeing yourself and acknowledging yourself as a way to repair that. That’s how I’m thinking about reparenting. Reparenting, I call it, or re-loving the inner child, too.

Even though this collection was heavy, I saw that there was joy, sometimes, even as a contradiction. I’m especially thinking about the first poem at the beginning of the collection, “Heredity.” The first stanza reads:

And then further down the fifth stanza reads:

So, how do you balance the joy in a collection that explores the heartbreaking reality of being black and alive in this world?

I remember being in therapy once and my therapist saying, “I think it’s time to start thinking not just about how to survive, but how to thrive in your life.” And I was like, oh, that’s really interesting. I feel like my mindset has been like, oh, my God, how do I work through this thing again? Or I’m still reeling from this thing that has happened to me. And I’m like, okay, how do I thrive? And so it was a challenge for me to think about. I think I started looking for that even in the two figures that we talked about, the matriarch and patriarch in the collection. What are those moments of joy that I did experience with them or that they were able to exhibit within all of this? And isn’t that kind of a miracle to see that that’s possible.

And I think in even a more macro way, there’s this essay that Jesmyn Ward wrote about how her husband died during the pandemic and she’s talking about all these joyful moments. I mean, that was the most heartbreaking thing. And one of the most heartbreaking things, and she’s talking about joy. She’s talking about the pandemic. She’s talking about all of the racially motivated violence, that was really potent in that time. I’m like, okay, this is something that we just do as a people. We find joy somehow. Even in the midst of whatever’s been going on. And so I think that’s something I’ve learned from just being a black person, observing other black people in my life, feeling seen by them. It’s like witnessing, yes, you’ve gone through this thing but you’re also dancing today, or you’re also laughing at a joke. That’s a pretty incredible thing.

Can you tell me about Johnson-Boria Creative and some of its offerings?

So, I have been spending a long-time teaching writing, I teach on the college level. I help coach writers and so it’s a combination of all that creative stuff like my teaching experience, but I also have this experience doing creative communications for different organizations or small businesses and some tech startups. I’ve done some work for mostly surrounding narrative. And how they want to talk about themselves, how they want to integrate that narrative within their day-to-day work. And so, I feel like that’s the creative aspect that has no bounds. It can be in the corporate sector quotes, it can be in non-profit, it can be in a writing classroom.

And so that’s, that’s what I offer. It’s how to approach things creatively to build a narrative that sustains and also that is honest and humanistic. To get people to learn about who you are, tell your story, whether you’re an individual or an organization or a business. So that’s what it’s been about and I’ve worked with some really cool organizations from a company focused on black breastfeeding to [an] education startup.

So, it’s been really cool to do that work. And it’s also like, anytime I do my writing or anytime I do a workshop that’s the presence I bring, the creative enterprise as the entity that’s bringing it.

Name a poet that has been a source of inspiration for your writing practice.

I’m going to have to say Lucille Clifton, because she’s probably the first person I read that said blatantly, “I write to heal.” And I feel like sometimes in literary spaces, I don’t really often hear that simplicity or that directness. And I think that really struck me and I’m like, okay, writing poems is deep work. It’s not just writing poems. [Lucille Clifton] talked about so much. I’ve been returning to her work about mothering lately since now I’m in that space. So, yeah, it’s gotta be Lucille Clifton, but there’s so many.

Recommended reads from Tatiana Johnson-Boria