One of Alabama’s most eccentric figures says goodbye

This is an opinion column.

I can’t recall if accident or intent brought me to Jim Bird.

But there I was, eight years ago, gawking at the towering art he’d built from junk in a hay field off the highway to Demopolis in Alabama’s Black Belt. There I was, banging on his door, a little concerned about a pair of nearby “guard turkeys,” with no idea what else to expect.

Bird answered in rumpled blue-and-white pajamas, as a dog named “Dog” barked a welcome. The rest of the day was magic.

He told me of his art – a towering tin man and fantastical beasts built of hay and scraps and imagination – and the lifelong love story with his wife Lib that inspired his creations. He told jokes and stories of frogs that were really about life, and he laughed, and he made me laugh.

Jim Bird didn’t think of himself as an artist. He just liked to make stuff. He made a lot of people happy.

I don’t know how best to describe Jim Bird. He was a dyslexic artist and an accomplished engineer, trained at the Merchant Marine academy. He was inventor and philosopher and storyteller and sailor and dancer and tour guide – an unusual character worthy of Big Fish, to be clear – but none of that does him justice.

To understand him you might have to know how he died.

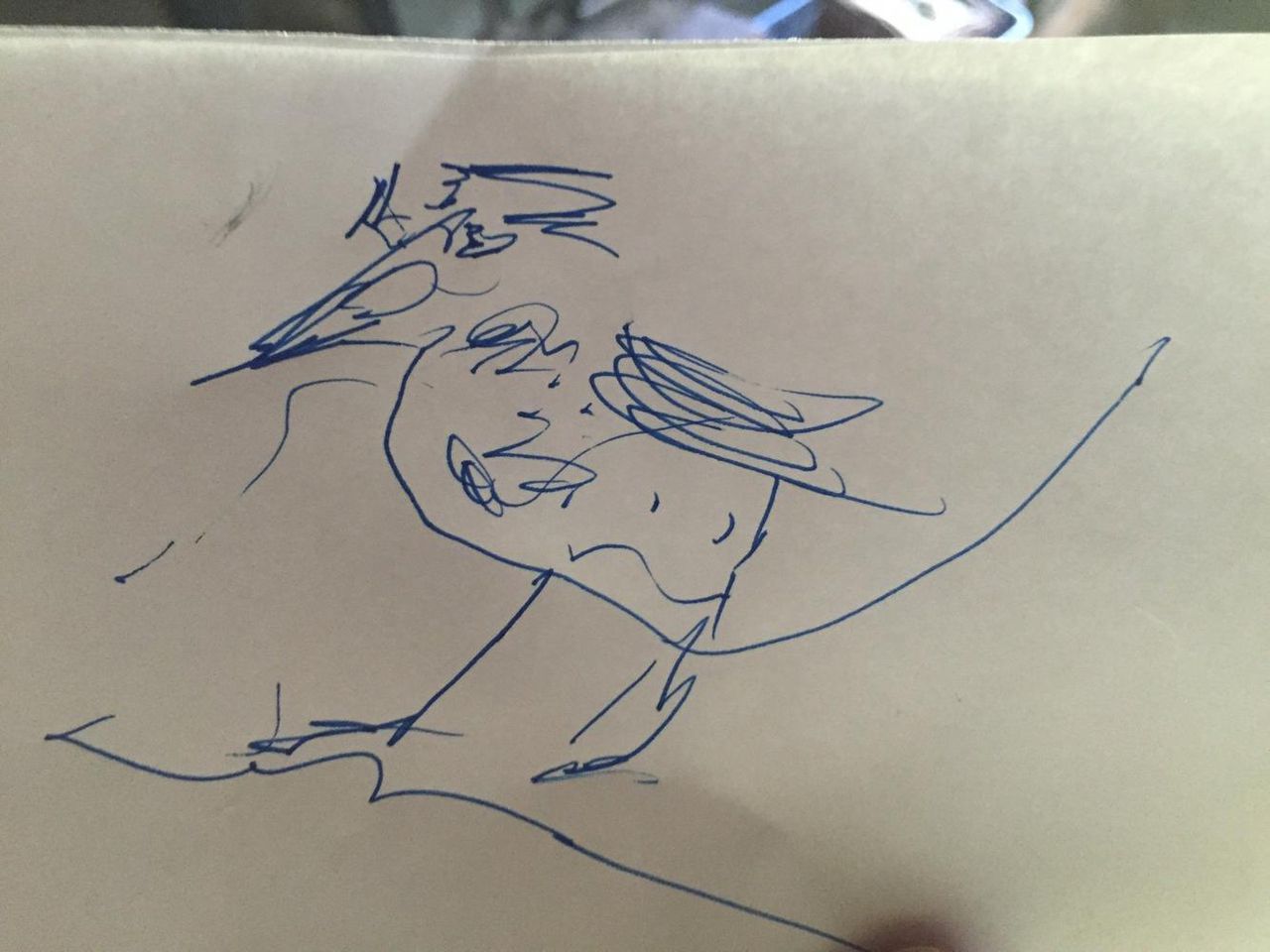

Bird, 96, of Forkland, Ala., passed away Monday night amid children and grandchildren. He built his own casket when he began to suspect the end was near, and adorned it with the likeness of his own unique signature, a scrawled picture of a bird. His wit remained sharp as his body failed.

This is how Jim Bird signed his name. And his casket.

He will be buried in that box Saturday, wearing a purple hat with a red plume, because he once wore it to a memorable party, and a blue-and-white sweater he loved. He thought it made his eyes pop.

After he is in the ground there will be a party, of course, daughters Grace Sneed and Avery Bird said. There will be friends and family, in a pavilion where his home stood before it burned a few years back, in the shadow of all that hay art. And then, you can bet, there will be dancing. He loved to dance.

This man died as he lived. As he damn well wanted. With family and friends and laughter and creativity. With stories he told, and stories told about him.

RELATED: This isn’t an odd story. It’s an Alabama love story.

Bird’s last words, spoken a few days earlier, had been hard to make out, his granddaughter Alison Bird said. But it was clear the last thing he tried to tell was a story. “Because that’s what he did.”

Jim Bird’s biggest artistic endeavor is his 32-foot “Tin Man.” It is made with bathtubs, barrels and a feed bin. (John Archibald/[email protected]).

In the days since, as his condition worsened, family members gathered around to tell him stories too, because they knew he enjoyed them, and because – as it turns out – that’s what they do, too.

“We were telling stories about him and making him laugh,” Alison Bird said. “He couldn’t open his eyes or anything, but he would lift his eyebrows every time we said something funny. So I know he could hear us. I know he was enjoying that. Those eyebrows went up every time he wanted to laugh.”

Bird’s preacher stopped by to pray with Bird on Monday night. He died before the amen.

It was a storybook life. And a storybook ending. But what of his legacy?

Not his family, which seems just fine, but those fields full of giant caterpillars and alligators, monsters and hay-bale helicopters and pigs with pink ears. The floats he built for Demopolis’ Christmas on the River. The people who travel to Forkland to camp on his land along Rattlesnake Bend on the Tombigbee River. What of all that?

I’m not worried.

RELATED: Jim Bird’s unusual church

I’m reminded how the first thing Jim Bird ever told me was a tale about a frog that hopped carelessly into a vat half full of milk.

That old frog thought it was a goner, doomed to die an unfrogly death in a sea of white foam.

But it kicked and swam, and kicked and swam, and in a day or so the milk began to thicken. It kicked and swam some more, on and on, and on the third day he’d churned that milk into butter.

So he climbed up the butter and hopped on back to his lily pad life.

“Don’t ever give up,” Bird told me then. “Just keep on kickin’, and it’ll work out.”

I think it will.

Jim’s son Archie – Alison’s dad – has worked to preserve the old art, and add more. Each May the family holds its “May Hay Day,” in which family and friends and strangers gather to touch up the hay art and build a new project. There is barbecue and beer and bands and stories. Always stories.

This year’s, on May 20th, will be a special one, Alison Bird said.

Jim Bird’s story will live on. Of course it will.

John Archibald is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for AL.com.

Jim Bird and his family have made hay an art.