On the frontlines of pesticide exposure

Editor’s note: This story is the first of “Adrift,” a three-part series by Environmental Health News, and palabra, a multimedia platform of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, on pesticide use in California that finds rural communities of color and farmworkers are disproportionately exposed to some of the most dangerous chemicals approved for use in agriculture.

This story and video were produced in collaboration with Voices of Monterey Bay.

By Claudia Meléndez Salinas

SALINAS, Calif. — Yanely Martínez was at work in 2017 when she received a phone call from her son’s school in Greenfield, an agricultural city in California’s Salinas Valley. Victor, 10, was having a severe asthma attack and his inhaler was nowhere to be found.

Martínez, an educator, soon realized pesticides were the likely culprit. Victor smelled something sweet before he had trouble breathing — a smell associated with one of the pesticides local activists were trying to get banned at the time. Later, Martínez discovered a field adjacent to the school had been fumigated before dawn.

“The application was at 4 a.m., and he got sick at 1 p.m. That’s how long the pesticide stays in the air,” she said.

Hundreds of millions of pounds of pesticides are applied to California crops each year, the largest share of agricultural pesticide use in the United States, where an estimated one billion pounds are applied annually. According to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation, 209 million pounds of active ingredients found in pesticides were applied in the state during 2018 alone.

Across the country, communities like Greenfield are largely neglected by state and federal regulators when it comes to addressing pesticide drift, leaving residents to battle county by county to find out how pesticides are affecting local air quality and to demand stronger protections.

There are no federal limits restricting the amount of agricultural pesticide mixtures allowed in the air. Despite pesticide links to health effects including nausea, headaches, asthma attacks, cancer, lower IQ and learning disabilities like autism, change has been slow, piecemeal and often driven by those most affected.

Victor Torres embraces his mother, Yanely Martínez, outside his former middle school in Greenfield, California. Both are members of the organization Safe Ag Safe Schools, which works for stronger pesticide protections. Photo Zaydee Sanchez for EHN/palabra.

Pesticide use and sale is regulated by different agencies, beginning with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which evaluates safety based on potential harm to people and environment, and down the line by state regulatory agencies and counties, depending on the patchwork of laws in each state.

But despite myriad laws intended to minimize pesticides’ harm to people and the environment, a growing body of research points to the disproportionately adverse effects of pesticides on people of color, particularly Latinos.

“Disparity on pesticide exposure has been documented. It’s a problem,” said toxicologist Alexis Temkin, co-author of a recent study by the Environmental Working Group examining pesticide exposure in Ventura County, a significant producer of berries, citrus and vegetables about 250 miles down the Pacific coast from the Salinas Valley. The study found that areas of the county with higher percentages of Latinos and low-income residents were exposed to larger quantities of toxic pesticides.

It’s not just Ventura. A 2015 study about the impacts of pesticides in California communities of color, published by the American Journal of Public Health, found that pesticide use was the pollution type with the greatest racial, ethnic and income disparities in the state.

More than 95% of agricultural pesticide use occurred in 60% of zip codes with the highest proportions of people of color. An analysis of state data by the group Californians for Pesticide Reform shows that in 2018, California counties with a majority Latino population used more than 900% more pesticides per square mile than those with a Latino population of less than 24%.

And several broader studies have documented that members of communities of color and poor communities in the U.S. are more affected by pesticide exposure than the rest of the country.

“Pesticides are more likely to harm people of color because of firmly entrenched policies and laws that stack the deck against them,” said Nathan Donley, environmental health science director at the Center for Biological Diversity. Donley co-authored a 2022 study that concluded disparities in pesticide exposure are perpetuated by weak regulation and enforcement such as laxer protections for farmworkers than for other occupations, and different standards for people exposed to pesticides via food residue (consumers) than for occupational exposures.

In California’s Central Valley and Central Coast regions, it’s largely through the advocacy of those like Martínez’s family that protections have been implemented.

Decades of struggle for pesticide protections

Martínez entered politics in 2015 to campaign for public office. A year later, as a member of the Greenfield City Council, she realized the impact of pesticide drift. She joined a struggle that began decades ago and has had some wins. They include the posting of “danger” signs outside fumigated fields and more recently, a pilot program to notify three schools in the county when and where pesticides are applied.

But local piecemeal solutions are dwarfed in the face of a powerful pesticide industry that has successfully lobbied to keep hazardous pesticides on the market for decades, and an agricultural industry that relies on the chemicals to produce multimillion-dollar crops — even in California, one of the most environmentally-regulated states in the country.

According to the most recent report, the sale of pesticides in the U.S. totaled $9 billion in 2012, an estimated two-thirds for agricultural use. A growing chorus of scientific experts is calling out the EPA and other regulators for bowing to industry pressure and failing to use the best science in assessing pesticide exposure risk.

“One of the myths people may have, or that our government has tried to portray, is that the U.S. has the strictest, most health-protective regulations of pesticides in the world,” said Mark Weller, statewide strategist for Californians for Pesticide Reform. “About half of all the pesticides by pounds applied in the Monterey region are banned in at least half a dozen countries in the world. We don’t have the strictest, most demanding regulatory system.”

An agricultural field covered with a plastic sheeting on the outskirts of Watsonville, Calif. on Sept. 11, 2022, displays a warning sign after it’s been fumigated with the pesticide chloropicrin. The sign warns workers not to enter from Sept. 6 until Sept. 16. Photo by Claudia Meléndez Salinas for EHN/palabra.

‘Our air is being poisoned’

On the 60th anniversary of “Silent Spring,” Rachel Carson’s seminal 1962 book about the environmental harm caused by pesticides, nearly 30 activists stood outside Monterey County’s government building to demand reduced applications of 1,3-Dichloropropane, a fumigant also known as 1,3-D or its commercial name, Telone. It’s the third most used pesticide in California, contributing to asthma-triggering particulate and ozone pollution and capable of increasing cancer risk more than seven miles away from application.

Many of the activists are members of Safe Ag, Safe Schools, a coalition of three dozen organizations across two counties in California’s Central Coast that have successfully lobbied lawmakers to restrict pesticide use near schools.

Member Yajaira García read a passage from Carson’s book. She then compared environmental conditions on the Monterey Peninsula, home to world-renowned golf courses and multimillion-dollar mansions along the Pacific Coast, to the Salinas Valley – just a 30-minute drive inland where farmworker families live in close proximity to agricultural fields.

“Our air is being poisoned by pesticides,” García said. “When you compare the air of the (Monterey) Peninsula, ours is highly polluted by pesticides … This is environmental racism.”

Yajaira García, left, speaks at a Sept. 27, 2022, press conference outside the Monterey County Government Center in Salinas, California. García, a member of Safe Ag, Safe Schools, was joined by about 30 community members to protest the use of 1,3-Dichloropropane, also known as Telone, in local agricultural fields. Photo by Claudia Meléndez Salinas for EHN/palabra.

Activism for farmworker protections has been a mainstay on California’s Central Coast since agriculture became the area’s economic engine.

Many of these efforts are driven by Latinos, who comprise a significant portion of the population in California’s agricultural counties. In the 1970s, inspired by the United Farm Workers and the leadership of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, many farmworker activists highlighted pesticide exposure as an urgent workplace hazard in the Salinas and Central valleys. Schools emerged as another focal point.

Angelita C., the mother of a child who attended a Monterey County school, sued the EPA in 1999 for racial discrimination, as the school’s student population is overwhelmingly Latino and the surrounding fields were frequently fumigated with methyl bromide, classified as an “acute systemic poison.” The EPA’s Office of Civil Rights found the allegations were substantiated and air monitoring emerged as a tool to address the issue.

California established three pesticide air monitors in 2011 in the entire state — in Monterey, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties — to detect pesticide drift and establish safety thresholds. In 2017, the state Department of Pesticide Regulation’s (DPR) Air Monitoring Network expanded from three to eight monitoring stations across the state. After funding expired in 2020, the number shrank back to four.

For activists, it’s one step forward and two steps back. Without the data provided by the monitors, it’s impossible to tell what pesticides linger in the air, how far they travel and whether the safety thresholds are being met.

“Scaling back the air monitors is just another example of the state’s long history of pesticide secrecy,” Weller said.

Pesticide impacts on children’s brains

When pregnant with her second child, María Isabel Ramírez lived in Watsonville, the so-called Strawberry Capital of the World, 20 miles north of Salinas. Her family lived in an apartment surrounded by fields — strawberries, apples, blackberries. Her husband was a pesticide applicator. At the time, she was unaware of the effects of pesticide exposure.

“I thought [pesticides] protected fruits and vegetables,” she said in Spanish. “I never investigated, I didn’t know anything. When he came home from work, I would wash his clothes along with ours. That’s how we began with these problems.”

The problems included developmental issues in her second and third children, now 23 and 20, respectively. Her second child is on the autism spectrum, and the third has a learning disability — issues not shared by her first and fourth children, who were born while the family lived further away from agricultural fields.

María Isabel Ramírez speaks at a Sept. 27, 2022, press conference outside the Monterey County Government Center in Salinas, California. Two of her children have developmental delays that Ramírez believes were caused by the family living in close proximity to agricultural fields treated with pesticides in nearby Watsonville. Photo by Claudia Meléndez Salinas for EHN/palabra.

Links between pesticide exposure and developmental disabilities are well documented by the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study. Run by the University of California, Berkeley, the long-term study is one of the most comprehensive works on pesticide exposures among children in farmworker communities. One of its findings concludes that prenatal exposure to certain pesticides is strongly linked to lower IQ and learning disabilities.

“When we started our study in 1999, we knew the acute effects of pesticides. We knew what happened when people are poisoned by pesticides — they end up in the emergency room,” said Dr. Kim Harley, associate director of the Center for Environmental Research and Community Health at UC Berkeley. “What we didn’t know was the effect of chronic, low-dose ongoing exposure to pesticides to people who live in the community, particularly to … pregnant women, fetuses and young children.”

In the 22 years since the study began, Harley said, she and her colleagues have found that children whose mothers had higher levels of pesticides in their bodies — particularly organophosphates — had poor verbal skills and lower IQ scores. “By the time they reached school age, they had more ADHD-type behaviors, more autism-type behaviors and more decreased brain activation on brain imaging scans,” she said.

Pesticides as air pollutants: a regulatory hot potato

California has been at the forefront of controlling air pollution from vehicles, but critics accuse regulatory agencies of not paying enough attention to pollution in rural communities, where the majority of pesticides are applied.

In response, the Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) and the California Environmental Protection Agency convened a working group in 2021 to draft a roadmap for transitioning to more sustainable pest control, such as using natural predators like aphids and lady beetles. The roadmap was released on January 26, and DPR will be receiving public comments until March 13.

People who live in rural areas face heightened risks from agricultural pesticide drift. This photo, taken on Sept. 11, 2022, shows a housing development adjacent to a vineyard in Watsonville, a small, Latino-majority city that has for decades sought stronger community and worker protections from pesticide exposure. Photo by Claudia Meléndez Salinas for EHN/palabra.

“Maintaining a keen focus on environmental justice and equity is integral to the department’s mission of protecting human health and the environment, our goal to accelerate a systemwide transition to safer, more sustainable pest management, and our day-to-day work,” said DPR spokesperson Leia Bailey in an email. In response to an interview request, Bailey wrote the department preferred to answer questions in writing.

Pesticide application in California is much higher in counties with a robust agricultural industry and a high concentration of Latinos, DPR data shows. In Fresno County, in California’s Central Valley, 35.7 million pounds of active ingredients were applied in 2018, the most current data available. Fresno, a top producer of almonds, grapes and pistachios, has a population of more than one million people. Fifty-four percent identify as Latino, and less than 25% identify as white only.

The city of Fresno consistently ranks among those with the highest air pollution in the United States, along with other cities in the agriculture-rich Central Valley such as Bakersfield and Visalia. Fresno County routinely fails to meet the country’s minimum standard for ozone pollution. It’s also the county with the largest pesticide use in the state.

But without specific pesticide pollution targets set by the federal government, with a limited monitoring network to detect pesticides and with different agencies establishing different safety exposure levels for different pesticides, regulation is a hot potato that gets tossed from agency to agency — to the confusion of the public.

Toward national solutions to pesticide exposure

Following the publication of Pesticides and environmental injustice in the USA, the study co-authored by Donley, a nationwide coalition of environmental and labor groups are urging the U.S. EPA to implement its recommendations.

In a Nov. 16, 2022 letter to the EPA, the coalition laid out nine actions the agency could take. Among them are a national monitoring system to collect pesticide data, using a special provision of the Food Quality Protection Act to determine safe exposure levels for children, and medical monitoring for people across the U.S. working closely with pesticides – something already happening in California for workers who apply organophosphates.

Many farmworkers “work in the fields for decades. If they start being monitored early on, then we can see what harm they’re being exposed to and prevent those caused by pesticides,” Yajaira García of Safe Ag, Safe Schools said.

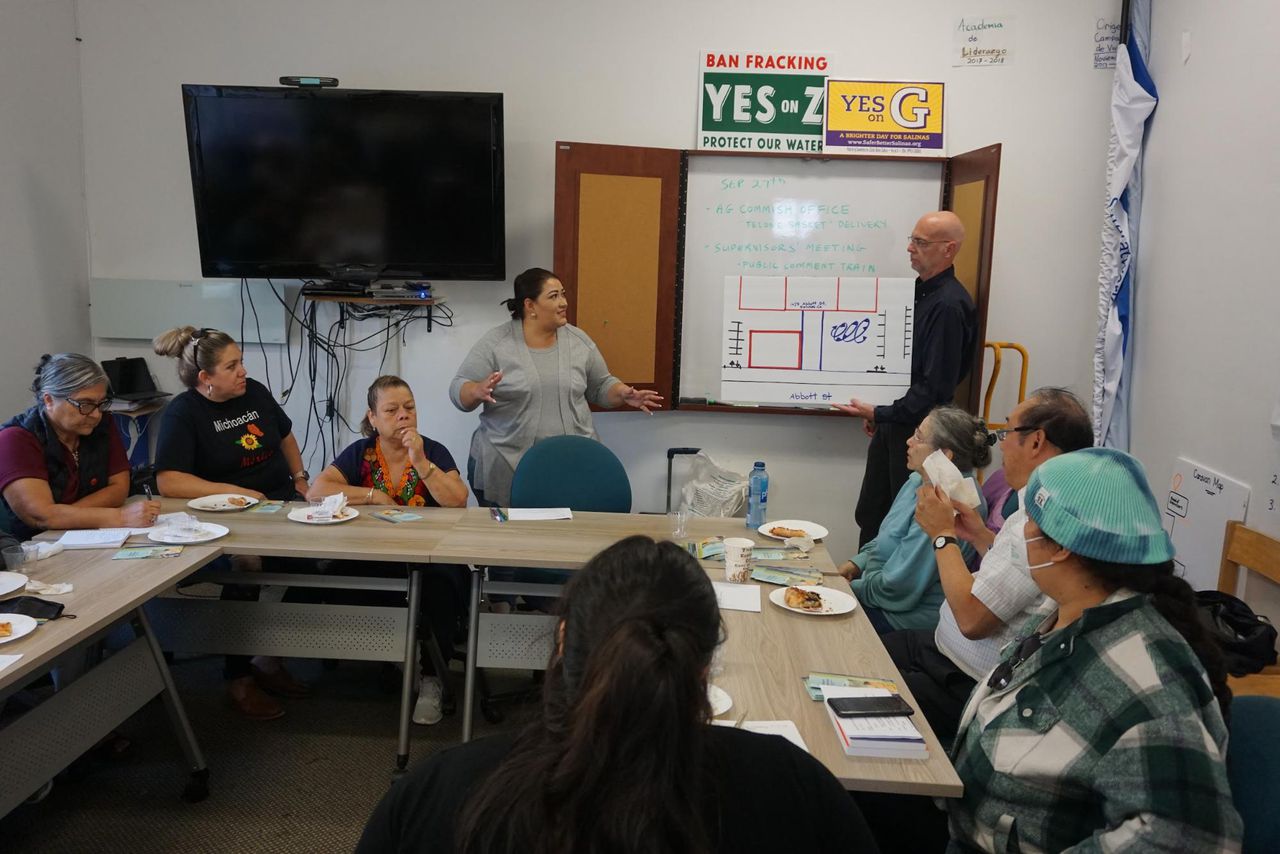

Yanely Martínez and Mark Weller lead a meeting of Safe Ag, Safe Schools in Salinas, Calif., on Sept. 15, 2022. The group was preparing for a rally to protest the use of 1,3-Dichloropropene in agricultural fields. Also known as Telone and 1,3-D, the fumigant is banned in the European Union. Photo by Claudia Meléndez Salinas for EHN/palabra

The proposals are ambitious and the likelihood of complete implementation is uncertain, Donley admits. But the signatories, which include the Farmworker Association of Florida, the Bullard Center for Environmental & Climate Justice at Texas Southern University and more than 100 other groups, intend to hold the Biden administration accountable.

“We are pushing extremely hard to get some of these protections put in place, but we recognize it’s always been a David and Goliath battle and we need to keep fighting,” Donley said.

After decades of struggle to protect their communities and those who put food on the table, activists in the Salinas Valley look at hard-earned victories — air monitors, the ban of methyl bromide and a statewide pesticide notification system planned for 2024 — and know they played a part, even if they remain frustrated by the slow pace of change.

Driving home to Greenfield, García admires the green patchwork of row crops that blanket the Salinas Valley and make her swell with pride. The fields are not only a source of food for millions of people, but have also provided for her parents, Mexican immigrants who toil in those fields along with thousands like them.

“I’ve always been super proud, but I hate being proud of fields that are killing our environment, our people,” García said. “I love seeing fields but I don’t love how hard they can be to our community.”

Claudia Meléndez Salinas is an author, journalist, open water swimmer, and a big cat lover. Photo by Víctor Almazán.

Marielle Argueza contributed to this report. Claudia Meléndez Salinas is an author, journalist, open water swimmer, and a big cat lover.