New school choice option a âtop priorityâ for Ivey: Whatâs the impact on public schools?

Education savings accounts, or ESAs, have spread like wildfire since the pandemic, with 15 states now operating some kind of ESA program. To supporters, they represent educational freedom. To opponents, they’re a threat to public school funding.

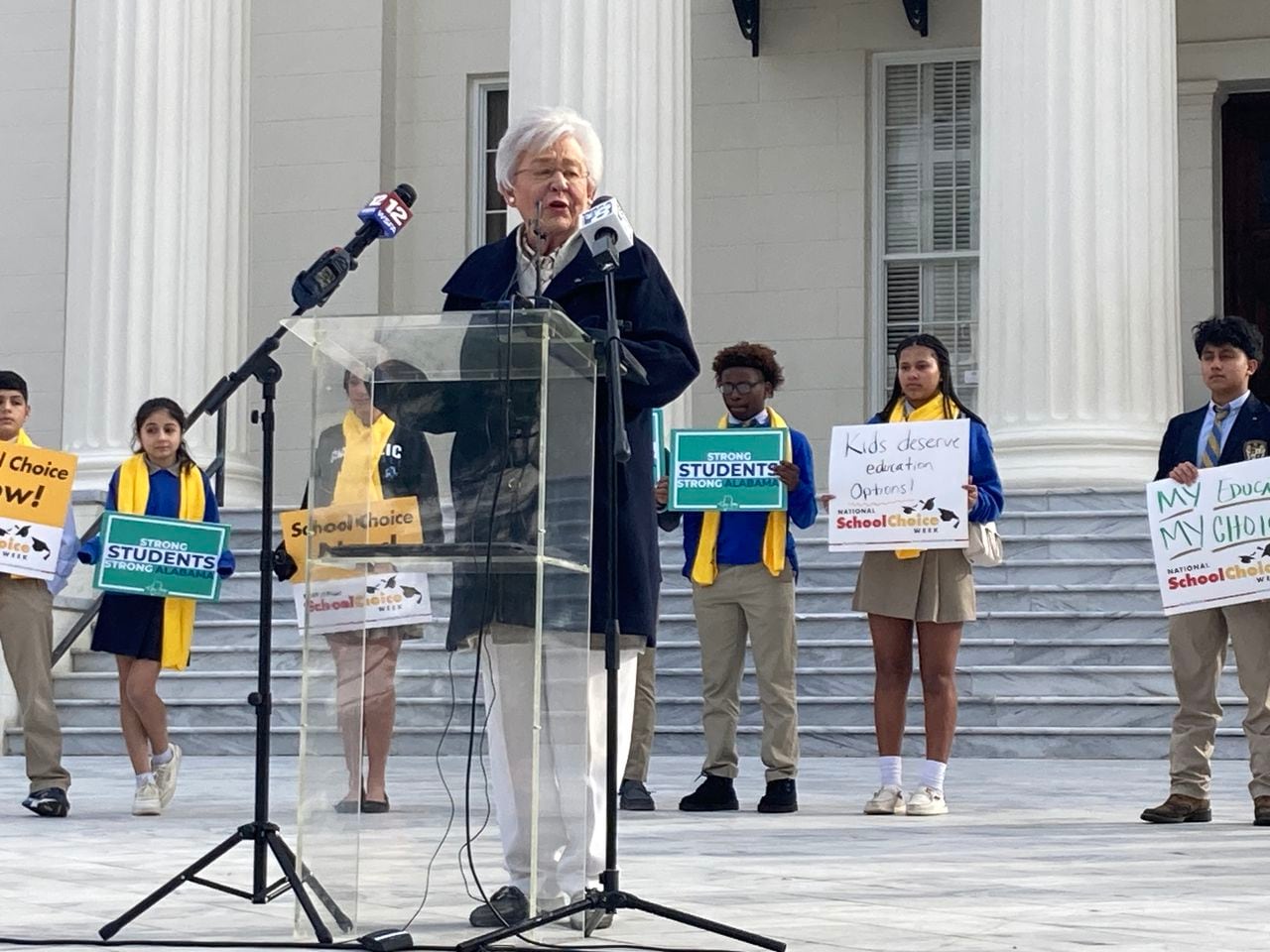

ESAs failed to get support from top Republicans last year, but prospects for passage look different this year. Gov. Kay Ivey said providing ESAs to students in Alabama is her top priority for the legislative session, which starts Feb. 6. She said her office is working on an ESA bill but it has not yet been filed.

That’s a turnaround from saying she would focus on “improving the school choice we already have” – meaning charter schools and Alabama’s tax credit scholarship program – during last year’s State of the State Address.

ESAs are accounts established by the state where periodic deposits are made that parents can then use to pay for goods and services related to their child’s education. The state determines which students and which expenses are eligible.

Most states have eligibility requirements either based on income or whether the student has a disability, but four states – Arizona, Florida, Iowa and Utah – have universal ESAs, meaning all students are eligible.

Rep. Ernie Yarbrough, R-Trinity, told school choice supporters during a rally Monday that he plans to file a bill that will look a lot like last year’s PRICE Act that would offer an ESA worth $6,900 to each student in the state. During a four-year phase in, costs would rise from $47 million to $697 million according to the fiscal note attached to the bill.

AL.com wanted to ask folks in public schools what impact ESAs could have on their public schools.

Anthony Sanders is the principal at Greensboro Middle School in Hale County. He said he is particularly worried about the cost of universal ESAs and that he doesn’t see how ESAs will benefit the 230 middle school students enrolled in his school.

“From my perspective,” he said, “this could be money that could be used to fully fund assistant principals, math and reading coaches to support teachers, and interventionists to support at-risk students.”

Instead, he predicts students already in private schools will most benefit. There is one private school in Hale County, according to federal and state records, with 280 students.

Sanders pointed to improvements Alabama students have made in recent years, including test results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress and expansion of career technical programs.

“I am afraid that we will lose some ground in those areas if we divert funds because of ESAs.”

Pleasant Home Principal Barry Wood leads a 480-student K-12 rural school in Covington County, which shares a border with Florida. When asked his thoughts on how ESAs might impact their school, Wood said he is concerned for a lot of reasons.

“There’s only so much room at the table,” Wood said. “I know right now we’re operating under a surplus and I think there’s a tendency to think that that kind of money will always be there.” Wood is referring to three years of surplus income tax revenue that state lawmakers have stashed away for a rainy day.

“Any time you start splitting up a pie with legislation, it does concern me.”

Wood said there are education initiatives that state lawmakers created that, while good for students, the state hasn’t fully funded. “We’ve made a lot of progress with the Literacy Act and the Numeracy Act,” he said, “but those are not fully funded to the degree we’d like them to be.”

“We don’t have math coaches,” he said, which are supposed to be provided under the Numeracy Act, which focuses on improving foundational math skills. In kindergarten through fifth grade.

Federal pandemic relief money has paid for summer learning programs, which schools are required to offer for students in the elementary grades as part of those initiatives.

For students at Pleasant Home School, federal relief funding has paid for interventions and to bring class sizes down, Wood said.

Federal pandemic relief will no longer be available after September.

Wood said he doesn’t know if students already in public school will use the ESAs to pay for private school tuition because there is only one private school nearby, Guardian Angel Christian Academy. According to Privateschoolreview.com, the school serves 101 students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

Most of the students not enrolled in public school are being homeschooled, he said.

“That’s perfectly fine and appropriate. That’s totally a parent’s right. But if now they’re going to be funded by the state with possibly no accountability, what’s to say that those numbers don’t grow.”

State Superintendent Eric Mackey told AL.com he hasn’t seen any draft bills outlining requirements for students who get ESAs, but he’d like to see those students take the same test public school students take.

Iowa’s is the only universal ESA program that requires students to take the same tests public school students take.

“I think there’s got to be some testing,” he said. In previous discussions about ESAs, independent school leaders have said they’d like to take the state test, but lawmakers would need to provide funding for that, he said.

“Because the legislature funds part of the test and the federal government funds part of it. We cannot use federal funds to pay for testing for private schools.”

Beyond testing, Mackey has other ideas about what he’d like to see in an ESA bill.

“I think there have to be some guardrails,” Mackey said. “You have to have accountability, financial transparency and there has to be a cap.” By “cap,” he means a maximum number of students or money or both.

Hoover Board member Craig Kelley said he is concerned about the impact ESAs could have on suburban schools like those in his city, which rely heavily on local property taxes to provide advanced academic offerings and strong extracurricular activities.

Kelley said he hasn’t seen a bill, and a lot of his concerns will depend on the details, like whether the amount of the ESA will be only the state-funded portion – $7,200 for the current school year – or if it could include some local tax, too.

Initially, he said, charter school supporters said local taxes wouldn’t be provided to charter schools, but now some lawmakers and charter school supporters have said local taxes should follow the student, too.

Those local property taxes are voted on by the community, he said, and if the community has no idea where their money is going or how well children are doing, support for those local taxes will wane.

“I do think long term, if people are allowed to continue to siphon off public education dollars, it will be the death of public schools.”