Many Alabama community college students never earn a degree. Advisers work to reverse the trend.

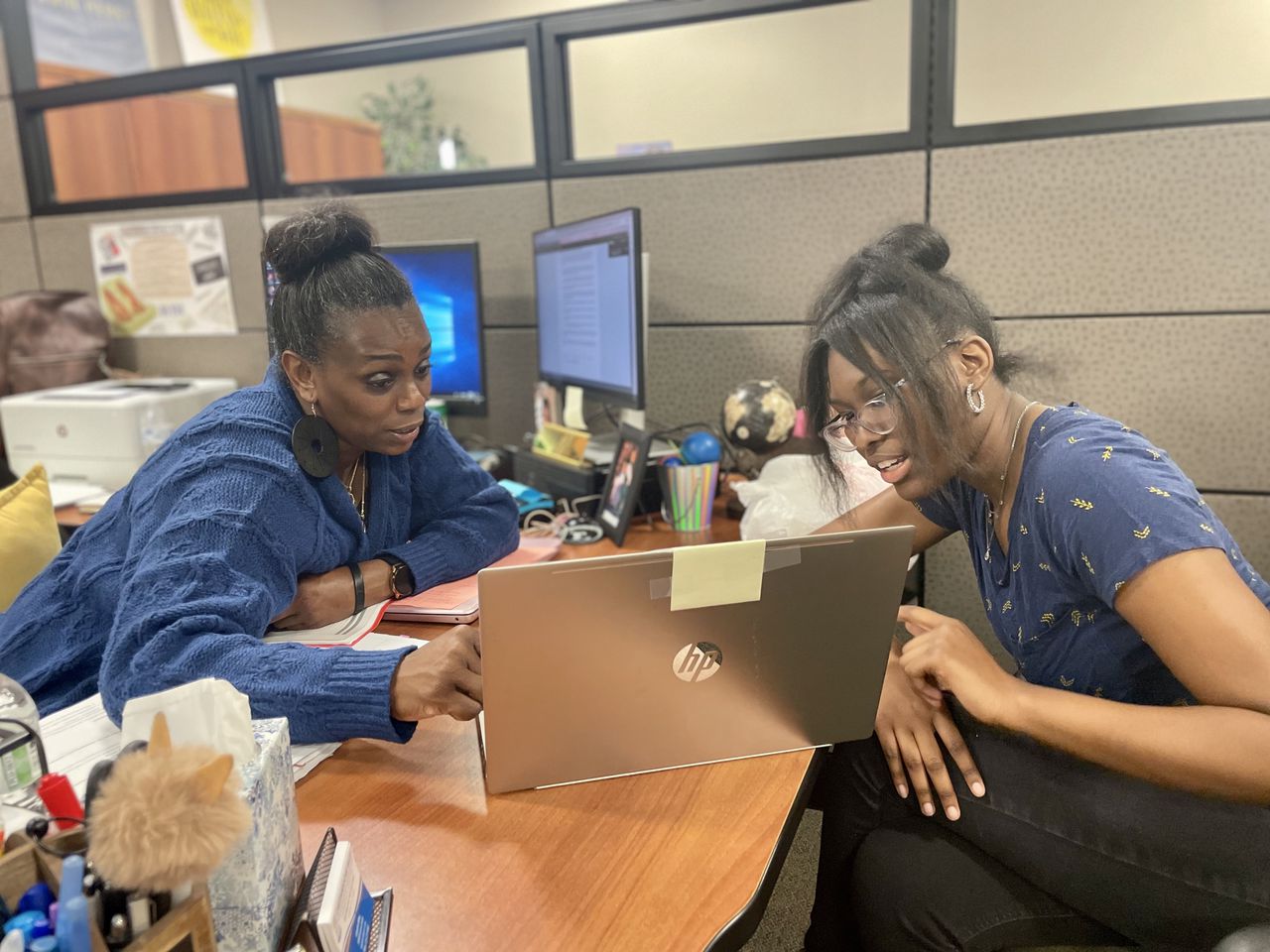

In a corner of a newly refurbished advising center, Shannon Feagins greeted Oryanan Lewis with a smile.

Lewis, a second-year student at Chattahoochee Valley Community College, chats about her academic progress. She is working on a medical assisting degree. She also mentions recent struggles with lupus, a chronic illness that nearly derailed her schooling.

“Ms. Shannon’’ is one of three new success coaches at the small two-year college in Phenix City, Alabama. Success coaches provide students with a range of services, including course registration, academic advising and career coaching, as part of a new program, called SENSE.

In another cubicle, success coach Latasha Wiley helped another student decide whether she should drop an anatomy class. In the background, a receptionist made a round of phone calls to remind students to turn in their assignments.

SENSE staff identify students in need of extra support in multiple ways: They automatically reach out to students in remedial classes, or students who are on academic probation. While every community college offers some advising support, the SENSE program is a unique effort in Alabama to automatically offer coaching to a certain group of students, and to guide them through whatever life and academic challenges occur until they successfully complete their program.

Read more Ed Lab: Community colleges across the U.S. are struggling. Why are so many students leaving?

Read more Ed Lab: Birmingham-Southern to stay open, ‘moving forward’ to next school year.

SENSE, now in its third year, aims to solve a problem that impacts community colleges across the country, as well as in Alabama: poor completion rates.

Nationally, about 36% of community college students who enrolled in 2018 graduated within three years. In Alabama, the rate is about 30%. Some don’t finish a program because they transfer to a four-year school early. But many drop out and don’t return.

“We lose a lot of students because they don’t think they have solutions to their problems,” said SENSE project coordinator Alisha Miles.

Now, for the first time in years, enrollment is on the rise in Alabama, and graduation rates are at an all-time high. But the state’s community colleges still are struggling to retain students and to get them certified for the workforce.

Statewide, the system serves 155,000 people, but not everyone is working on a specific degree or credential. Of about 17,600 first-time, degree-seeking community college freshmen who enrolled in 2019, just 10,000 were still enrolled in 2021, according to state data. Four percent of degree-seeking freshmen transferred to another Alabama college within two years. Another 39% did not transfer or re-enroll.

Advocates say a large group of students may be slipping through the cracks: People who face barriers that cause them to prolong their degree, or drop out of a degree program entirely.

“They’re doing great with their coursework, they’ve been on track and then one thing in life happens and everything falls apart,” said Chandra Scott, of Alabama Possible. “But instead of us understanding that, the first thing we say to them is that they failed.”

‘I definitely needed the guidance’

In interviews with AL.com, Alabama community college students said one of the biggest drivers in their success is a solid support system. Many needed an adviser who not only helped them with registration and financial aid, but also who kept up with their progress along the way.

“If we see that they want to see us thrive, then that would make the process a whole lot easier,” said Briana Mathis, a 30-year-old mother of two who is navigating her first year back at Wallace Community College in Dothan after dropping out from the college 10 years ago.

A decade ago, 51% of degree-seeking students re-enrolled at Wallace-Dothan after their first year. Last year, that rate was 59%.

The school now has a full-fledged support center that pairs each student with an adviser. It also recently hired staff to work specifically with adult learners. One of those staffers, Buffae Howard, recruited Mathis, helped her appeal a financial aid decision and checks in with her regularly to make sure she’s on track.

“I definitely needed the guidance, and I probably wouldn’t have gotten this far without the guidance,” Mathis said.

Community college students who spent longer periods of time or had multiple appointments with advisers were more likely to be engaged in their courses, researchers found in a 2018 survey. Another case study found wide-scale advising reforms contributed to a jump in graduation rates by 21 percentage points.

“What students are telling us is it’s important for them to be asked, ‘What are some challenges that you’re experiencing right now that will prevent you from being successful at this college?’” said Linda García of the Center for Community College Student Engagement. “Like, really getting to know the student.”

Success Coach Latasha Wiley, left, helps first-year student Amare Porter, right, with her class schedule at Chattahoochee Valley Community College’s advising center on Feb. 23, 2023, in Phenix City, Alabama. Rebecca Griesbach / AL.com

But not all schools offer the same level of support, García said.

A 2022 CCCSE report found that nationally, 53% of students said an adviser helped them to set academic goals and create a plan for achieving those goals.

Fewer respondents said a staff member talked with them about managing commitments outside of school or helped determine whether they qualified for academic assistance.

“I really had to figure that out on my own, versus having that hands-on assistance that I feel like most college students would want,” said Jahnelle Congress, a first-year student at Lawson State. She needed help determining a major, she said, but her school’s advising line never returned her emails or in-person requests.

“You need an adviser to help you figure out those things, and to not have that is kind of tough,” she said.

Is support for advising growing?

Advocates and experts say there’s a need for better – and more – advising at the community college level.

“We’ve got to get beyond saying. ‘Oh, we have that in place.’ Yeah, we have that in place and that’s great,” said Scott, at Alabama Possible. “But if they’re not able to serve all students, which should be the guiding star, then we’re missing the boat.”

In a 2017 study, University of Nebraska-Lincoln researchers found that while “prescriptive advising,” like class scheduling or registration, may be more valuable early on, long-term, or “developmental” advising can be better suited to help students define and achieve their individual goals.

But resources for more robust advising services are often scarce, they said.

“Funding is by far the biggest limitation to quality community college advising, and this includes being able to staff advising experts in the evenings and weekends, or at a distance, which is when and how many community college students are able to attend classes,” said co-author and UNL associate professor Deryl Hatch-Tocaimaza.

While Alabama’s community colleges mostly operate independently, they can share some funding and programming system-wide.

This spring, Alabama community college system leaders are working on new statewide measures to retain students, including appointment scheduling and a “student success scoring” system, which would help identify students who need help early, rather than waiting until they ask for it.

They also say they have bolstered staff training and are asking the legislature for about $3 million – up from the system’s current allotment of $600,000 – to hire a career coach for every college.

But it’s ultimately up to individual colleges to decide what type of support they need, said Ebony Horton, a spokeswoman for the system.

Technical schools, for example, may be more focused on hiring career coaches, while other institutions may have more students who need help transferring. Sometimes instructors take on advising roles, too, she said.

“That is such a small picture of what advising looks like, because that’s the only piece of advising that’s kind of managed from the system down,” she said. “Every other piece, we know, needs to fit what accommodates that college’s student body.”

‘A difficult task’

At Chattahoochee Valley, a five-year, $1.8 million federal grant supports the SENSE program, which aims to provide wraparound support to a variety of students.

The goal, Miles said, is for coaches to stick with students until they get a job or transfer successfully, and to help them overcome barriers along the way – be it transportation issues, lack of funding to purchase books or a lack of support from family members.

Antonio Davis, left, studies with a classmate in Chattahoochee Valley Community College’s new advising center Feb. 23, 2023, in Phenix City, Alabama. The college has hired success coaches that work with some students through the course of their degree and help solve any life or academic issues. Rebecca Griesbach / AL.com

“We’re trying to interject or put ourselves in the middle of those obstacles so that we can see higher completion rates,” she said. “But it’s still a difficult task because we’re fighting against a lot of things. Sometimes it’s personal issues that keep people from moving forward, and sometimes it could be financial, or it could be that they just can’t do it, and they just stop.”

Just over half, 54%, of first-time, degree-seeking students who enrolled at Chattahoochee Valley in 2019 completed their second year of coursework.

State data shows retention rates improved at the school by about four percentage points from 2020 to 2021, when the program began. Current students in the program said SENSE has helped them cross the finish line in both small and big ways.

Alaysha Hill, a first-year transfer student, said success coach Brandon Bliue helped her turn her grades around after a rocky transition. Another student, Cortez Rawlins, said he was struggling in one of his courses until a coach helped him come up with a detailed study plan.

Lewis, 20, is nearing her graduation date, and she credits that to a few people who noticed, and listened, when her grades started dropping.

During her first year on campus, Lewis said she almost lost her financial aid after chronic illness caused her to fail three classes. SENSE helped her get accommodations, then helped her come up with a plan to maintain the grades she’d need to keep her scholarship, she said.

“If I didn’t go in there and get the information and the support that I had, I don’t think I would be where I’m at now,” she said. “I most definitely don’t think I would have been in school still.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is part of Saving the College Dream, a collaboration between AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, and The Seattle Times, with support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Read more stories in the series here:

Community colleges are struggling. Why are so many students leaving, dropping out?