Lawmaker tries again to make fentanyl deaths manslaughter

Alabama lawmakers have approved several bills over the last couple of years in response to the plague of fatal overdoses caused by fentanyl, a deadly drug that authorities say is often added to other street drugs.

But one such bill that passed this year did not become law because of a mistake in the legislative process.

That bill, by Rep. Chris Pringle, R-Mobile, would have expanded the crime of manslaughter to include the act of selling or giving drugs containing fentanyl to a person who then dies from using the drug.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey mistakenly signed an earlier version of Pringle’s bill that would have applied the manslaughter penalty more broadly — to anyone who provides any controlled substance that caused the user to die. That bill covered any Schedule I through Schedule V controlled substance, a long list that includes fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and many others. Officials blamed the mistake on a glitch in new software that sent the wrong bill to Ivey.

Pringle is trying again to pass the manslaughter bill that applies only to fentanyl. Pringle, the Alabama House speaker pro tem, has pre-filed the bill for next year’s legislative session, which starts on February 6.

“If you and your friend go out and you get falling down drunk, and you’re driving your car at 100 miles an hour down the road and you wreck and kill your friend, you’re charged with manslaughter, you’re acting recklessly,” Pringle said. “If you’re distributing drugs laced with fentanyl, you’re acting recklessly. You should be charged with manslaughter, too.”

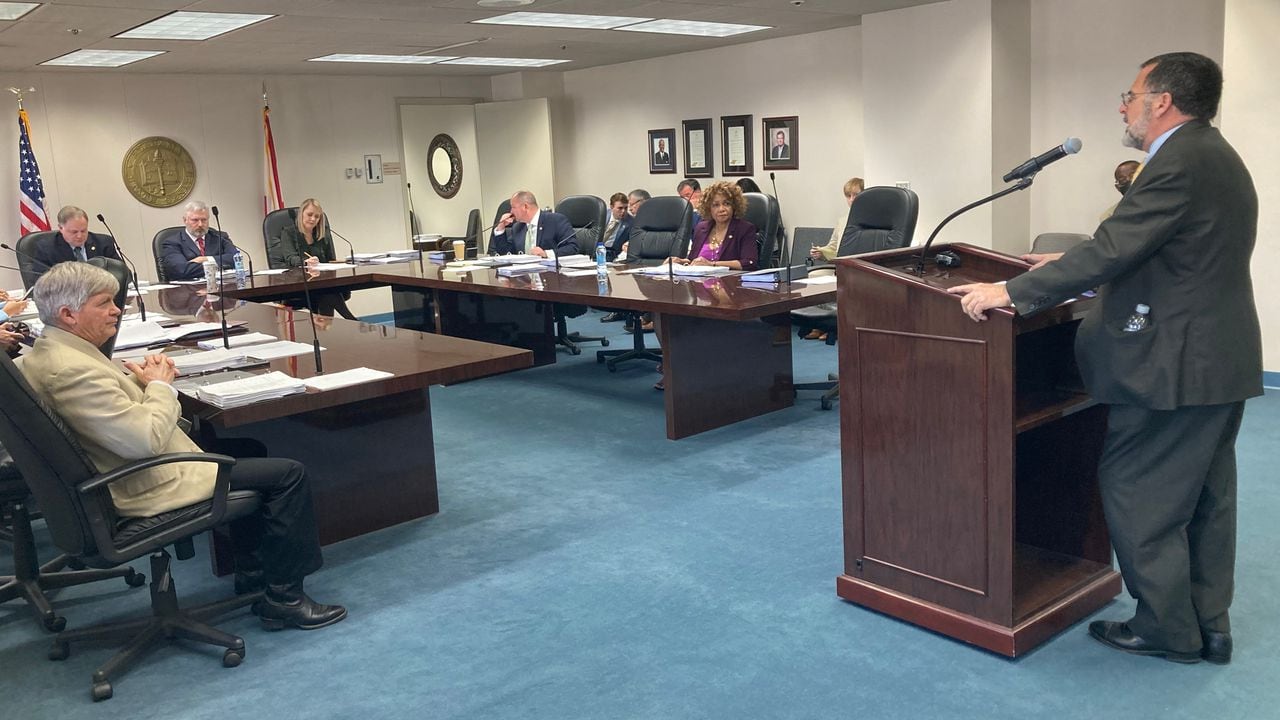

When Pringle explained his bill to the Senate Judiciary Committee in May, he talked about a friend’s son who battled addiction and died from an overdose after receiving an OxyContin pill laced with fentanyl.

“We know who sold it to the boy,” Pringle said. “We know who killed him.”

The Senate later approved the broader version of Pringle’s bill, covering all controlled substances. A conference committee narrowed the scope to fentanyl only before the bill won final approval, 99-0 in the House and 31-0 in the Senate.

But that version of the bill was mistakenly not sent to the governor, so it was never signed into law.

Under current law, a person commits manslaughter if they recklessly cause the death of another person. The manslaughter charge can also apply if a person kills another under circumstances that would normally be murder but if the act was committed during a sudden heat of passion. Manslaughter is a Class B felony, punishable by two to 20 years in prison.

What about the version of Pringle’s bill that the governor signed, the one that would apply the manslaughter penalty more broadly, to anyone who provided any controlled substance that caused a death?

Alabama House Clerk John Treadwell said it is doubtful that law is valid. It would have taken effect Sept. 1.

“It continues to be a legal question as to whether it is in effect but based on prior case law it would likely be determined that what the Governor signed was materially different from what the Legislature passed and would not be in effect,” Treadwell said in an email. “However, it appears that prosecutors are aware of the issue with the prior bill and the efforts to correct it with the new bill. As a result, it doesn’t appear that there have been any efforts to prosecute under that statute as amended in the bill from last session.”

Law enforcement, politicians, and health officials have for several years called attention to fentanyl, the leading cause of a surge in overdose deaths in Alabama and across the nation. In Alabama, overdose deaths involving fentanyl increased from 453 in 2020 to 1,069 in 2021, according to the Alabama 2023 Drug Threat Assessment.

Fentanyl is produced legally for treating severe pain. Illicit versions come in pill versions, powder, and liquid and are often added to other drugs, authorities say. Fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine. A lethal dose is about two milligrams, equivalent to a few grains of salt.

In Jefferson County alone, about 400 people died of overdoses in 2021, an increase of one-third over the previous record of 302 in 2020, and fentanyl was a cause in more than three-fourths of the deaths.

In April, the Alabama Legislature passed a bill to impose mandatory prison sentences for knowingly possessing one or more grams of fentanyl, which the law defines as trafficking. Two milligrams is considered a potentially lethal dose, meaning that one gram is enough to potentially cause 500 deaths.

In 2022, Alabama lawmakers passed a bill to make it legal to use and distribute test strips that detect the presence of fentanyl in other drugs, an effort to prevent overdoses.

Pringle said he thinks the manslaughter charge is appropriate even if the person providing the drugs is not aware that they contain fentanyl because they caused somebody’s death by doing something illegal.

“It’s like all the other bills, if we save one life, it’s worth it,” Pringle said. “Because we’re losing friends and family members all over this nation because of this fentanyl problem.”

Read more: Health groups sound alarm about deadly fentanyl: ‘All it takes is 1 time’

Drug overdoses killed more than 1 person per day in Jefferson County last year, an all-time high