Law professor speaks Sunday on ‘Jim Crow’s legal executioners’

A law professor who has spent a decade researching racial violence in the South will speak on the topic Sunday at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

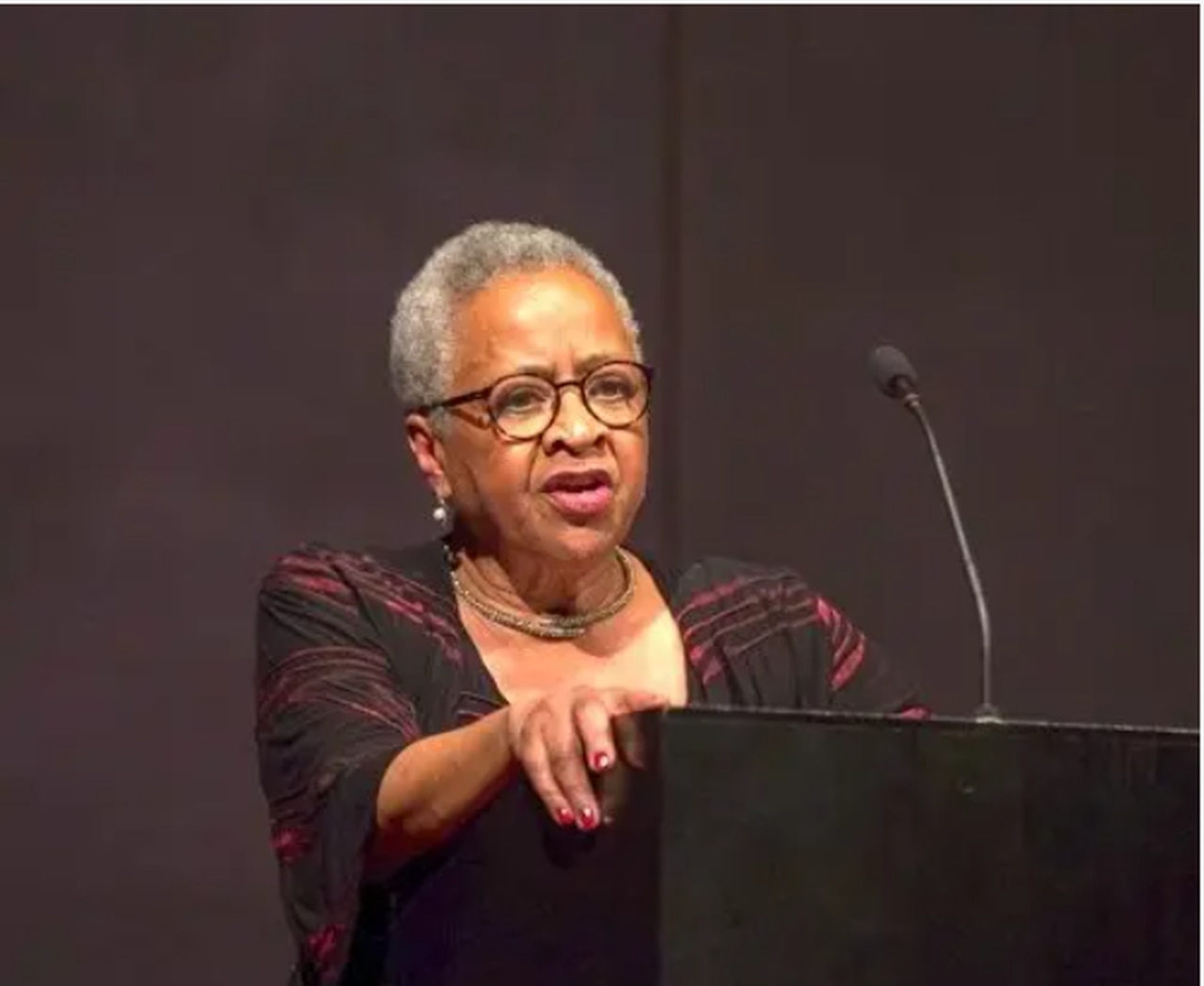

Margaret A. Burnham, director of Northeastern University’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, and author of “By Hands Now Known: Jim Crow’s Legal Executioners,” will discuss her book Sunday at 2 p.m.

Much of the research was done at the Birmingham Public Library archives.

“Birmingham figures large in this book,” Burnham said in a phone interview this week. “Birmingham had a reputation as one of the most violent cities not just in the South, but in the country. It has a history of industrial violence as well as racial violence.”

Her research focused on the Deep South from 1930 to 1955. “We know a lot about Birmingham in the 1960s,” Burnham said. “We don’t really know as much about this earlier period.”

The Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project has compiled “a searchable archive that pulls together and digitizes violations of human rights,” Burnham said.

In one case in 1957, a Black man named Judge Aaron was castrated by a group of white men as an initiation rite for the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham, she said.

“Judge Aaron tells his story, but tries to go on with his life,” Burnham said. “There are historical traumas that have not fully been recognized.”

Such incidents contributed to overall racial distrust, since perpetrators were seldom prosecuted, or were exonerated by all-white juries.

“In failing to prosecute kidnappers, southern states were, in effect, immunizing their acts: conferring upon them a legal right to do a legal wrong,” Burnham writes in the book; “perceiving the police and the lynch mob as interchangeable, Black communities deemed law and legal institutions antithetical to their interests.”

In 1948, 4,500 mine workers, Black and white, staged a wildcat strike in Edgewater, Alabama, to protest the killing of a popular 54-year-old Black union man named C.T. Butler.

Butler was a coal miner, pastor and union organizer who was the target of company harassment. While walking to work, he was shot to death by two U.S. Steel company police officers. Butler’s widow sued the company and won a $10,000 judgment from an all-white jury, in a rare show of solidarity with a Black victim of violence.

Burnham also documented violence by all-white police departments who often killed Black men with no repercussions.

Jim Baggett, archivist for the Birmingham Public Library, said that from 1939-72, Birmingham police kept a set of 3×5 index cards of police shootings. Those 109 cards are now part of the library archives, although he said it is likely an incomplete documentation of police shootings.

The justice project has identified nearly 130 cases in which Blacks were killed by police in Jefferson County. White officers were rarely held accountable.

“These things went to coroners, who were complicit,” Burnham said.

Among the victims documented in the project were Atmas Shaw, O’Dee Henderson and Eugene Burt.

Burt was shot to death on Feb. 8, 1950 at his home. The officer, J.A. Hale, had been involved in four other shooting deaths.

Henderson, 25, was an employee of Tennessee Coal and Iron who was beaten and shot to death while in custody in Fairfield on May 9, 1940.

Shaw, 42, a father of three, was killed on April 17, 1948. He was on his way to make a payment on the homestead he inherited from his father. He was carrying about $1,000 when he had an encounter with Birmingham Police Officer Steve Wideman that led to a confrontation. Shaw fled, Wideman followed, and a struggle ensued. Shaw’s head hit the base of a stone building, according to police. He was taken to Hillman Hospital. Before he died, Shaw told his family by telephone he had been badly beaten by police, who warned the hospital not to treat him. The family never recovered the $1,000 he had been carrying.

“I hope people get to know their city a little bit better,” Burnham said. “The Birmingham story is a national story.”

The program is sponsored by the Birmingham Public Library and copies of “By Hands Now Known” will be available for purchase.

See also: Hugo Black monument dedication set