LA schools bet on tutoring for post-pandemic recovery, but progress is slow

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

By Pilar Marrero

Lourdes López, 39, is an immigrant from Oaxaca, Mexico, who lives with her husband and their three children and brother-in-law in a sparsely furnished two-bedroom apartment in South LA.

On school days during the pandemic when classes were being taught remotely, Lourdes gave her oldest daughter, now 13 years old with a love of math, exclusive use of the only bedroom the family of five uses.

“We would close the door because she needed to study and concentrate,” Lourdes remembers, recounting how she also had to wait for the (computer) tablets from the school district “that took a good while” to arrive.

In the living room, the young mother struggled to get her other daughter, a ten-year-old with Down syndrome – a congenital condition that includes intellectual disability – to pay attention to online classes by putting her arms around her and encouraging her to listen.

“She would say ‘I don’t want to be here,’ and I would have to hold her tight, while the youngest one, who wasn’t getting any instruction, would just play and make noise. It was difficult.”

Lourdes stayed home to keep up with her children’s education, occasionally selling Amway products while her husband went to work.

She had things to learn, too.

“We just weren’t used to this; we didn’t know how to open a web page or click on the program,” she remembers.

The effort paid off: her oldest is now in seventh grade at Irving Magnet School in Northeast Los Angeles with STEAM concentration (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics), but she worries about her two youngest children.

“My second daughter was in a special program, but she didn’t get any instruction after they closed the schools, not until the following year,” she says. “The youngest was barely starting preschool and didn’t get anything.”

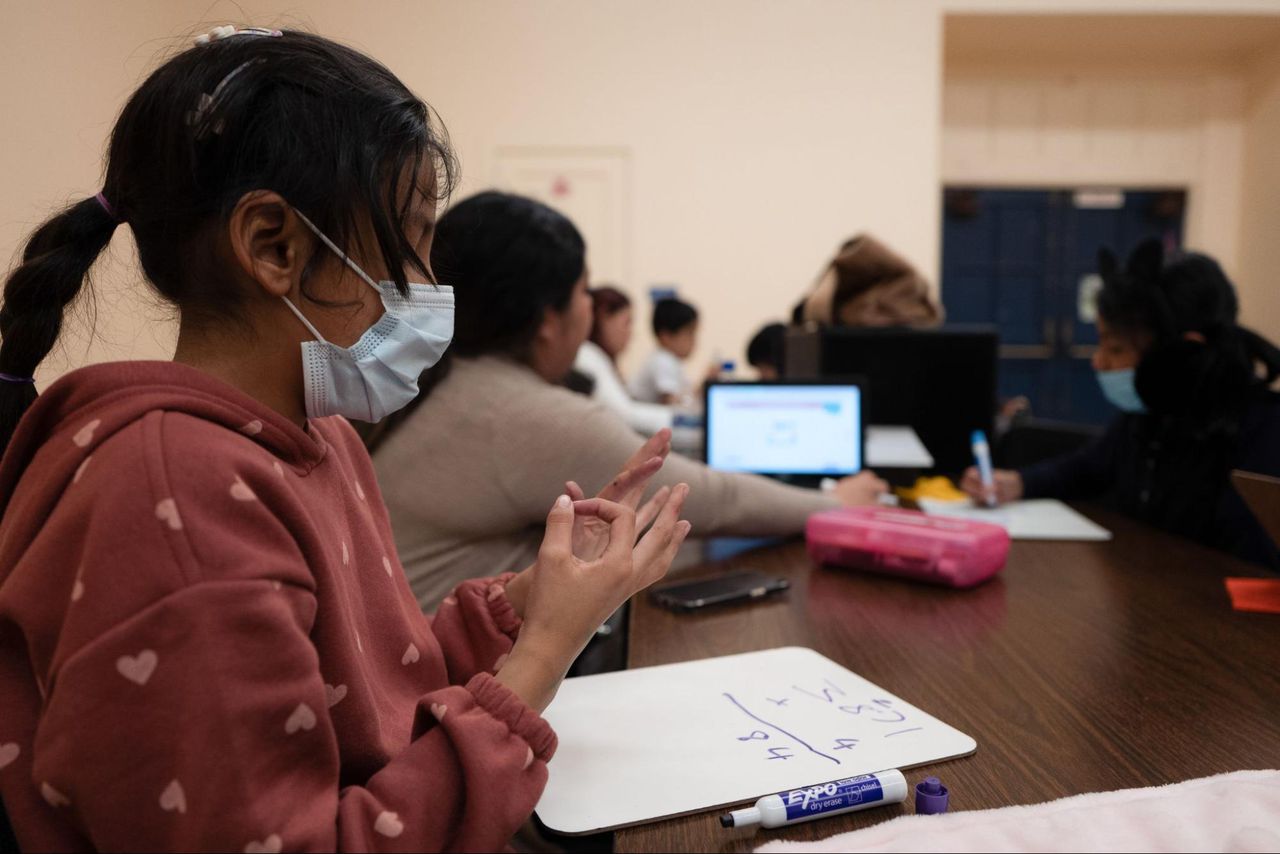

Like Lourdes, many parents worry that their children won’t be able to make up for school time lost during the pandemic. They know that the school district is flush with billions in federal funds received during the pandemic to help it recover, but believe the program’s rollout has been too slow and uneven, often depending on local implementation at the school level and leaving many children behind. Tutoring has become one of the critical programs that LAUSD leaders hope will get students back on track, and some schools have implemented what is called “high dosage tutoring,” which involves in-person, one-on- one, small group classes to help kids catch up.

LAUSD, with half a million students – 74% of them Latino – is the nation’s second-largest school district. It’s a sprawling district that includes public schools in the city of Los Angeles as well as smaller cities and unincorporated neighborhoods in Los Angeles County. (The controversy over the availability of tutoring is just one of several major challenges facing Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), including a dispute over wages for district employees that led to a recent 3-day strike.)

“High dosage means that we are infiltrating the whole system with lots of tutoring,” said Claudia Vela, principal at Aragon Elementary in the Cypress Park neighborhood. “It’s face-to-face tutoring. We do have homework help online if you need it, but we are focusing on one-on-one, high-quality tutoring with a tutor for small groups of students that need it the most.”

High-dosage tutoring is not yet offered at every LAUSD school, although it has been promised district-wide. And on a Friday evening in February, Lourdes joined a Zoom call with other Latino parents to talk about the problems their kids are having getting the extra help they need at school.

They call themselves “Our Voice/Nuestra Voz, Communities for Quality Education.” It’s a small group, but they are highly motivated, meet weekly to hear speakers, discuss issues with each other, and attend school meetings.

Lourdes and others are frustrated. “They are giving a few extra hours of classes; that seems nothing to me for all the money they are receiving and what they can learn in that time,” she tells the other parents on the call. “I think it is a small crumb for us Latinos. I am not against the support; it seems very little to me.”

She mentions that her eldest daughter is taking Saturday school via Zoom at Irving Magnet, but she says her two other kids, both with special needs, have so far received little tutoring.

Other parents chime in.

“My daughter’s grades dropped quite a bit,” says Rocío Elorza, who lives in East Hollywood and has a daughter in middle school and a son in elementary. “So I asked for a meeting with the teachers, and only on Tuesday they started tutoring her.”

Another mother, who identified only as María Pilar, said that one of her children struggles in math. “And in his school in Highland Park, they still are “planning” the tutoring classes,” she says. “We don’t have any specific information yet.”

Silver linings for students

But at some LAUSD schools, tutoring programs are starting to show promise.

At Aragon Elementary, Vela talks enthusiastically about “schooling every single day of the week.”

“We know exactly who the students who need more support are,” she says.

Aragon is the gold standard in Los Angeles at the moment, offering three tutoring sessions daily after classes as well as Saturday school, with a total of 16 tutors hired from a private contractor and trained by staff. Funding for the program comes from federal and state programs for post-pandemic education recovery.

Tutoring at LAUSD includes various types of extra instruction: online homework help, in-person or virtual “high dose” tutoring with students in small groups, and something called “locally designed interventions,” where LAUSD teachers provide academic lessons after school or on Saturdays.

Vela’s enthusiasm for the project underscores the influence that principals have in determining how much tutoring is offered at their school. She says teachers at her school have seen plenty of anecdotal evidence that tutoring is helping, and test scores have gone up “24 points in reading and 16 points in math.”

Nadia, a shy English learner in fifth grade at the school, says she likes her English tutoring class and feels she’s making progress.

She is receiving extra help with reading three days a week and on Saturday, says her mother, Lucía Pérez, who has four kids, including Nadia. She says that before the pandemic her daughter was close to being reclassified as a regular English speaker, but online learning didn’t agree with her, and she was held back.

“I think the tutoring is helping her a lot,” she says. “And she loves it.”

But across the district, results are uneven.

The latest numbers on tutoring, released by LAUSD in March, show that only one in four students are getting one of the three types of tutoring. That’s an improvement from 1 out of 10 in November.

“There were a lot of challenges we were facing (in launching the tutoring program),” said LAUSD chief academic officer Frances Baez. She explained that vendors who provide tutors had to be vetted first, and then the companies had trouble finding enough tutors to hire.

“We were offering some sort of tutoring in the spring and summer of 22; in August of 2022, we launched on-demand tutoring with homework help.”

LAUSD received more than $4 billion in federal post-pandemic recovery funds under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. But the district has spent only about 50% of the funds, according to an analysis by Edunomics, a Georgetown University research institute exploring educational finance. The funds were available for districts to address pandemic learning loss and invest in infrastructure and programs to open and operate safely.

Tutoring is popular among parents, said Hanna Gravette, regional vice president in Los Angeles for Innovate Public Schools, a non-profit that trains and organizes parents to demand quality education. “During the pandemic, wealthy families sent students to private tutoring, but there was no way for our families to do that.”

About 80% of LAUSD students qualified for free or reduced-price school lunches before California instituted universal free school meals this academic year.

After schools returned to in-person learning in the fall of 2021, Innovate activists pushed LAUSD to do more, faster, after what they saw as a lackluster distance learning plan during the pandemic and the slow implementation of remedial programs.

“Parents in many poor areas were asking for tutoring, and they weren’t getting it,” said Gravette.

Innovate points to what they call “tutoring deserts,” which they define as underserved communities in Los Angeles where quality tutoring programs are nearly nonexistent.

Katy Meza, a parent leader at Innovate, says she lives in one of those deserts. Her ten-year-old son badly needed tutoring, but his school in the city of South Gate, a small majority-Latino city southeast of downtown Los Angeles and part of LAUSD, has been very slow to implement it.

Last year, parents from her community and Innovate lobbied the local government and got money from the cities of South Gate and Huntington Park to hire a private tutoring company.

“He had ten weeks of tutoring thanks to that,” she said. “But I know what is happening in his school is due to the principal, who is not active enough because other schools offer excellent tutoring.”

Even so, both Meza and Gravette credit LAUSD superintendent Alberto Carvahlo, who arrived in the district barely a year ago in February of 2022, with being willing to listen to different voices and correcting course when needed.

After meeting with Innovate parents in November, the district eased some of the regulations that were making it difficult for tutoring programs to be fully implemented, Gravette said.

Initially, the district wanted tutoring to be concentrated at the 100 lowest-performing schools – about 10% of the district – and for extra classes to be held only during certain hours, she added.

“In November, we asked him to remove some of those (regulations) and to open the floodgates if spaces weren’t filled. This month (February) they announced they are providing the high-dosage tutoring at every single LAUSD school.”

“In theory, parents should be able to go to the principal and say, I want high dosage tutoring provided at my school, but so far it has been hit and miss,” she added.

Carvalho continues to come under fire for the district’s response. “The help is not reaching all families that need it,” said Evelyn Alemán, from Nuestra Voice/Our Voice Communities for Quality Education. Alemán accuses the district of launching programs with much fanfare at press conferences but taking too long for improvements to reach all schools.

palabra requested an interview with Superintendent Alberto Carvahlo but the district offered Chief Academic Officer Frances Baez instead. Tom Kane, an education economist at Harvard University, recently characterized the effect of the pandemic on student achievement as the equivalent of, “a band of tornadoes coming through schools,” and has said that current efforts to catch up are likely to be insufficient.

But at Aragon, where an effective principal and staff have allowed for the rapid expansion of interventions and tutoring, teachers like Diane López see a difference in their student’s ability to catch up.

“Many got to third grade and didn’t remember how to do basic addition or subtraction, which they should have learned in first and second grade. Reading wasn’t as bad, but there were words they were not used to,” she says. “I see improvement with the kids that go (to tutoring).”

Vela thinks of one particular kid when considering how those extra classes may be helping the students.

“This teacher told me about how a particular student, Ivan, who is always falling off his chair and is all over the place, recently told her that he loves going to tutoring.”

“Ivan’s story is that his parents just separated; he hasn’t seen his mom in several months, he is disheveled, and he has many needs,” Vela adds. “So I always tell tutors that they are a role model for the students, a positive influence.”

Since Vela started as principal in October, the school has also added a music enrichment program to complement tutoring in academic subjects like math and English.

“It’s a beautiful community, beautiful students,” says a smiling Vela. “We decided to expand the music classes. And we also have an after-school orchestra, so we are very busy on Mondays. Our kids go to band and also tutoring, and we make it work. And we have seen the progress.”

Tutoring can work to address learning loss and accelerate learning, said Dean Pedro Noguera of the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California. “They (school districts) have the money to do it, but the question is how they are using it.”

Parents with kids in many schools wonder when they will get the full benefit of the funds that LAUSD has received to help the students. They are pushing for more.

Elementary school parent Paula Meneses regularly participates in LAUSD’s English Learners Advisory Committee (ELAC) meetings.

“We had a meeting at ELAC and we asked for five days of tutoring; it would be so much better. They are getting three days, and the sessions are less than an hour each. We want at least five days.”

“It’s not much, after everything they’ve lost”, said another parent, María Hernández.

__

Pilar Marrero is a journalist and author with extensive experience in covering social and political issues in the Latino community. As a disinformation monitor for the National Conference on Citizenship’s Algorithmic Transparency Institute, she has been tracking COVID-19 misinformation, the anti-vaccine movement, and politics. She is the author of “Killing the American Dream,” which chronicles 25 years of immigration policy mishaps in the United States and their consequences for the country’s economic future. The book is also available in Spanish. Pilar is an Associate Editor at Ethnic Media Services in San Francisco, and a consulting producer for “187, the Rise of the Latino Vote,” a documentary by Public Media Group of Southern California. She worked as a reporter and editor at La Opinión newspaper for 26 years.

Zaydee Sanchez is a Mexican-American visual storyteller, documentary photographer, and writer. Inspired by her upbringing in the city of Tulare in California’s agricultural San Joaquin Valley,, her work is rooted in addressing the complexities of migration. With a focus on blue-collar workers, gender, and displacement, she seeks to make meaningful and impactful work.