Judges to decide if Alabama fixed discrimination in Congressional map

Three federal judges who ruled last year that Alabama’s congressional district map most likely violated the Voting Rights Act will decide whether a new map approved by the Legislature in July fixes the discrimination against Black voters.

Circuit Judge Stanley Marcus and District Judges Anna M. Manasco and Terry F. Moorer will hear arguments at the Hugo L. Black U.S. Courthouse in Birmingham on Monday.

The judges ruled last year that Alabama’s map, with one majority Black district out of seven in a state where one-fourth of residents are Black, gave Black voters less of an opportunity than other Alabamians to elect a candidate of their choice.

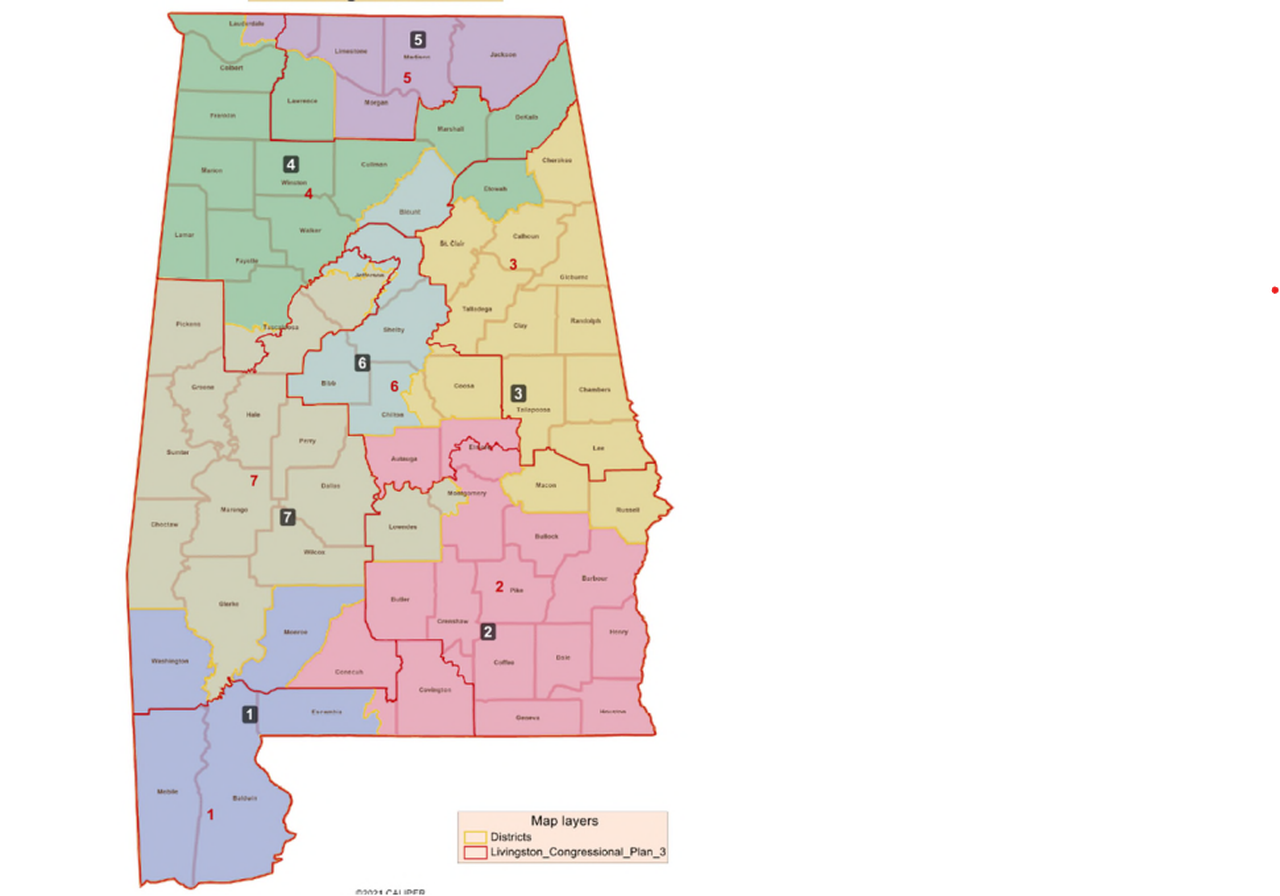

The new map makes substantial changes, with about a dozen counties changing districts, but does not add a second majority Black district.

The organizations and Black voters who challenged the old map say the new one disregards last year’s ruling, which the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed in June.

“Alabama’s new congressional map ignores this Court’s preliminary injunction order and instead perpetuates the Voting Rights Act violation that was the very reason that the Legislature redrew the map,” attorney Deuel Ross of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and others representing the plaintiffs wrote in their objection to the new map.

In response, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall and the state’s lawyers wrote that the Voting Rights Act does not require proportional representation for minorities. They say the new map more closely follows traditional map-drawing principles because districts are compact and because what they define as communities of interest, including Mobile and Baldwin counties, the Black Belt, and the Wiregrass, are intact to the extent possible.

“There are many ways for a State to satisfy (the Voting Rights Act’s) demand of ‘equally open’ districts,’” the state’s lawyers wrote. “The 2023 Plan’s fair application of the neutral principles of compactness, county lines, and communities of interest is one such way, even if it does not create proportional representation.”

The stakes are high. If the judges uphold the new map, Republicans are all but certain to keep their hold on six of Alabama’s seven congressional seats. If the court rejects the map, a special master and cartographer appointed by the court will draw a new map to be used in next year’s elections.

The Congressional Black Caucus and Congresswoman Terri Sewell, D-Birmingham, filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs, as did Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin and other Black elected officials. The National Republican Redistricting Trust has weighed in with a brief in support of the state. The U.S. Department of Justice filed a statement with the court asserting its “substantial interest in the proper application” of the Voting Rights Act.

Alabama Secretary of State Wes Allen told the court the state needs a map in place by Oct. 1 to prepare for next year’s elections.

The litigation started almost two years ago. In October 2021, the Legislature approved a congressional map, as required after every census. Several groups of plaintiffs challenged it in court. The combined case the judges will hear on Monday is called the Milligan and Caster case, named after two of the individual Black voters who sued.

Last year, the three-judge panel held a seven-day hearing and ruled that the plaintiffs were likely to prevail on their Voting Rights Act claim and that “the appropriate remedy is a congressional redistricting plan that includes either an additional majority-Black congressional district, or an additional district in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice.”

The judges said the plaintiffs’ claims passed key legal standards for Voting Rights Act cases, including that Alabama’s Black population was large enough and geographically compact enough to form a reasonably drawn second majority Black district, and that voting in Alabama is racially polarized.

“The appropriate remedy is a congressional redistricting plan that includes either an additional majority-Black congressional district, or an additional district in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice,” the judges wrote.

The Supreme Court put a hold on the ruling last year to allow the map to be used for the 2022 elections but did not rule on the merits of the case at that time. The justices heard oral arguments in October. In June, they affirmed the likely Voting Rights Act violation.

That sent the case back to the three-judge court, which gave the Legislature a chance to fix the problem. The disagreement now is over whether the plan passed by the Legislature on July 21 was an “appropriate remedy.”

The new map leaves District 7 in west Alabama as the only majority Black district, with a Black voting age population of 51%, which is down from 55% on the old map.

District 2, which covers southeast Alabama, has the second highest proportion of Black voting age population, at 40%, up from 30% on the old map. The other five districts range from 7% to 25% Black.

The Republican majority in the Legislature, who passed the map on a party-line vote, said it makes District 2 the second “opportunity” district for Black voters that the court called for.

“The Legislature enjoys broad discretion and may consider a wide range of remedial plans,” the judges wrote. “As the Legislature considers such plans, it should be mindful of the practical reality, based on the ample evidence of intensely racially polarized voting adduced during the preliminary injunction proceedings, that any remedial plan will need to include two districts in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

The plaintiffs say recent election results in the new District 2 show that Black-preferred candidates, or Democrats, would have little or no chance. In 16 of 17 statewide races since 2016, Democrats received fewer votes in the new District 2 than Republicans, with the outlier being Doug Jones’ win over Roy Moore in the 2017 special election for the U.S. Senate.

In all 11 statewide races pitting Black vs. white candidates since 2014, the Black candidate received fewer votes in the new District 2, an average of 42%.

“In this regard, the new CD2 (Congressional District 2) offers no more opportunity than did the old CD2,” the plaintiffs wrote in their objection. “In both plans, Black voters are unable to elect their preferred candidates. SB5 (the new map) continues to violate this Court’s order because nothing about the new CD2 meaningfully increases Black voters’ electoral opportunities, nor decreases the dilution of their vote.”

Alabama’s 2021 congressional district map, with the new 2023 map superimposed with red lines. The Supreme Court ruled the 2021 map likely violated the Voting Rights Act. A three-judge court will decide whether the 2023 map fixed the problem. (Image is from court brief by lawyers for the state).

The Department of Justice, in its statement of interest filed with the court, said historical election patterns are an important fact to consider whether the redrawn District 2 with a 40% Black voting age population would give Black voters a realistic chance to elect a candidate of their choice.

Woodfin, Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed, and other Black elected officials filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs on Friday. They said the new map does not follow the court’s orders.

“Instead, the Legislature has flouted its obligations in an effort to entrench power and to continue to undermine Black voters throughout the State,” they said. “We urge this Court to continue to press the State to fulfill its obligations under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.”

The brief was signed by Sens. Merika Coleman of Pleasant Grove and Linda Coleman-Madison of Birmingham, Reps. Napoleon Bracy of Mobile and Patrick Sellers of Birmingham, Jefferson County Commissioner Sheila Tyson, and Jason Ward, mayor of Lisman, a town in Choctaw County.

The National Republican Redistricting Trust, which filed a brief in support of the state, said the Voting Rights Act does not require or even allow forcing proportional representation while violating traditional redistricting principals.

“For that reason, any suggestion that the State is ‘defying’ the Supreme Court’s opinion in Allen by passing a law that follows traditional districting principles rather than racial proportionality makes no sense,” the organization said in its brief. “Here, given the nature of Alabama’s population and geographic dispersion — only 11 of 67 counties are majority black — it would be surprising to see proportional representation without a violation of traditional districting principles.”

But the Milligan plaintiffs, in their objection to the new map filed on July 28, said the Supreme Court has already found that maps proposed by the plaintiffs with two majority Black districts do not violate traditional principals.

“First, and most importantly, the Supreme Court agreed with this Court (the three-judge court) that politically cohesive Black voters could form majorities in two reasonably configured districts, yet (the new map) continues to permit the white majority voting as a bloc in the new CD2 to easily and consistently defeat Black-preferred candidates,” they wrote. “A remedy where ‘the majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate’ is no remedy at all.”

Both sides have indicated they do not intend to call witnesses at Monday’s hearing.

Marcus has been a federal judge since 1997 and was appointed by President Clinton. Moorer was appointed by President Trump and was confirmed by the Senate in 2018. Manasco was appointed by Trump and confirmed by the Senate in 2020.

Read more: Johnson: Plaintiff in historic SCOTUS redistricting case shed tears for late father after ruling