Johnny Mack Brown: Alabama Rose Bowl hero & Western icon

‘Whatever happened to Johnny Mack Brown, and Allan ‘Rocky’ Lane,’ ‘Whatever happened to Lash LaRue, I’d love to see him again.’

— The Statler Brothers, “Whatever Happened to Randolph Scott”

There have been a number of famous Alabama football players through the years, but only one has been name-checked in a Statler Brothers song and has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

That is, of course, Johnny Mack Brown, the Crimson Tide All-America halfback who later became one of the most popular and prolific cowboy movie stars of the 20th century.

It’s 98 years ago this week that Brown first made his mark nationally in Alabama’s debut Rose Bowl appearance, scoring two touchdowns in a 20-19 victory over Washington that helped carve out a space for the Crimson Tide and Southern football in general within the popular imagination.

Known as “The Dothan Antelope,” Brown was one of five football-playing brothers who emerged from that southeast Alabama town most famous for its annual Peanut Festival and went on to the University of Alabama. By the end of his life in 1974, he had nearly 200 film credits to his name.

“Johnny Mack Brown represents an uncommonly full and fulfilling story of celebrity at the intersection of life with not one, but two, powerful myths of American manhood,” historian Philip D. Beidler wrote in 1995. “In newspapers and sporting publications across the land, Brown found popular enshrinement along with such golden age heroes as Knute Rockne and Red Grange as the latest All-American champion of the college gridiron.

“And on the screen, during the heyday of the Hollywood cowboy, he inherited the mantle of stardom from the legendary William S. Hart and joined the Saturday-afternoon company of Tom Mix, Buck Jones, Ken Maynard, Hoot Gibson, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers as one of the most-popular Western movie entertainers of his era.”

From Dothan to Tuscaloosa

Born Sept. 1, 1904, as the son of shopkeepers, Brown starred at Dothan High School before earning a scholarship to Alabama in 1922. He arrived in Tuscaloosa just as the Crimson Tide was beginning to become a national power in football.

Alabama went 7-2-1 and lost the Southern Conference championship on the final Saturday of the season in 1923, then finished 8-1 and took home the league title the following year. The speedy Brown had begun to emerge as a standout that season, scoring three touchdowns in the season-opener vs. Union, returning a kickoff 99 yards for a score vs. Kentucky and scoring on long interception returns vs. both Georgia and Furman.

As former Alabama head coach Wallace Wade told it in 1986 shortly before his death, Brown — always a gifted runner — didn’t become a truly outstanding player until he improved his blocking and tackling prior to his junior year.

“He was a great runner and a great pass receiver but he was weak on defense,” Wade said. “Until he became a good defensive player, we couldn’t afford to play him. We had to have an all-around football player.”

Johnny Mack Brown, left, is shown with Alabama teammate Pooley Hubert in 1925. (Photo courtesy of the Paul W. Bryant Museum)Creg Stephenson/[email protected])

Alabama had its best team yet in 1925, with not only Brown returning but also quarterback Grant Gillis and ends Hoyt “Wu” Winslett and Red Brown (Johnny Mack’s younger brother). But the true leader of the team was fullback Allison “Pooley” Hubert, a burly Mississippi native regarded as among the toughest players of his era.

The Crimson Tide rolled through the regular season at 9-0, allowing just seven points total and playing only two games decided by fewer than 27 points. Brown scored a 55-yard touchdown in a 7-0 victory at Georgia Tech in late October, a game that featured 23 tackles by Hubert.

It’s not entirely clear when Brown acquired the nickname “The Dothan Antelope,” but it appears the first reference in print came in The Birmingham News on Nov. 15, 1925. In his account of Alabama’s 34-0 victory over Florida, longtime sports editor Zipp Newman described one sequence thusly “There was no catching the ‘Dothan Antelope,’ who was breaking loose for 10, 15, 20 and 30-yard gains.”

The Rose Bowl — first played in 1902 and continuously since 1916 — was the only postseason college football game at the time. Alabama was not the first choice of the lofty “Tournament of Roses” committee. Dartmouth, Yale, Illinois and Tulane all dropped out of consideration before an invitation was finally extended to Alabama.

“In those days, Alabama, or the Southern teams, weren’t noted for great football potential,” Brown told an interviewer years later. “But it seems like they thought perhaps we were lazy, full of hookworms or something of that sort. But nevertheless, after winning a couple of conference championships back in the South, we were invited out to play against the University of Washington, which at that time was one of the greatest football teams in America.”

Alabama was considered a heavy underdog in the game against Washington, and the Huskies took a 12-0 lead at halftime, but Brown and the Crimson Tide had something in store for them in the second half.

With Washington star halfback George Wilson temporarily out of the game due to injury, Alabama scored three touchdowns in the third quarter to take control of the game. First came a 1-yard scoring run by Hubert, then two touchdown catches by Brown — a 55-yarder from Gillis and a 30-yarder from Hubert.

Alabama suddenly led 20-12.

Washington scored again in the fourth quarter on a Wilson touchdown pass but could not pull out the victory. Brown — once considered too poor on defense to play full-time — helped clinch the win by making an open-field tackle on Wilson in the game’s closing moments.

Back to Hollywood … eventually

During its weeklong stay in Southern California, the Alabama team spent a good portion of its time socializing with alumni and celebrities in the Los Angeles area. Noted publicity man Champ Pickens had arranged for the various civic clubs in Alabama to send telegrams to the Crimson Tide players, imploring them to win the Rose Bowl for the glory of the Southern states.

It was also during this period that Brown had a fateful meeting that would determine the course of the remainder of his life. He struck up a friendship with George Fawcett, a Hollywood actor who was making a film in Birmingham during the fall of 1925.

Brown’s brother, Billy, told author Tommy Ford for his 1992 book, Alabama’s Family Tides,” that Fawcett told Johnny Mack “if you’re ever out in California, come see me.” Fawcett thought the 5-foot-11 (tall for his era), handsome, athletic, clean-cut Johnny Mack had the “it factor” to make it in the fledgling motion picture industry, which was still in the midst of the silent film era.

“Well, Johnny thought he was just trying to be nice,” Billy Brown said. “But sure enough, they wound up going to the Rose Bowl to play Washington. After the game, George contacted Johnny and asked if he could make a movie test while he was out there. … He passed, and MGM Studios offered him a contract right then.”

Johnny Mack Brown wife with Cornelia “Connie” Foster Brown in 1935. (Birmingham News file photo)Creg Stephenson/[email protected])

Brown did not take the offer immediately, however, as he still had business to attend to in Tuscaloosa. He returned to Alabama and married his college sweetheart, Cornelia “Connie” Foster, in early 1926, and went to work selling insurance and coaching the Crimson Tide’s freshman team on the side.

MGM continued to send telegrams to Brown, each time offering him more money to sign a motion picture contract. Eventually, they made him an offer he couldn’t refuse, and the Browns moved to Hollywood.

“Who at that time would have thought they were going to be a movie star from Alabama?” said Ken Gaddy, retired executive director of the Paul W. Bryant Museum in Tuscaloosa. “He was active in the plays on campus and those kinds of things when he was a student, and it was just one of those things where he had the look that the movie people wanted.

“… Can you imagine going to your parents and saying ‘hey, I want to go to Hollywood?’ That’s a major step for anyone today, let alone almost 100 years ago.”

Brown was never directly involved in football again after that, though he maintained a close relationship with Alabama and the Crimson Tide over the years. He certainly wasn’t forgotten in the football world, as the National Football Foundation elected him to its Hall of Fame in 1957.

The NFF/College Football Hall of Fame, which opened near Cincinnati in 1978 and moved to Atlanta in 2014, now requires that inductees be named to at least one All-America first team. All-America teams were more of a nebulous thing during Brown’s day, said Kent Stephens, official historian for the College Football Hall of Fame.

“If the current rules of the College Football Hall of Fame were in existence when he was elected in 1957 were his place today, he would not be a Hall of Famer,” Stephens said. “In 1925 there were like 12 major All-America teams and of the 12, he made third-team on just three of them. So he really was not the star of the team. That was of course Pooley Hubert, who was named to six All-America teams.”

“… There were a lot of great halfbacks in that era — Swede Oberlander at Dartmouth, George Wilson from Washington, Red Grange at Illinois, so Brown was pretty far down that list. In the 30 years since his playing career and his election, he’d become quite a notable person for all the movies he made. So I think his election was probably born on his notoriety more than his ability. He did have a great Rose Bowl game. So that’s sort of how he became elected, so to speak.”

Starting at the top

There is no debate as to Brown’s film credentials, however.

Brown made his screen debut in 1927 with a cameo as himself in “Slide Kelly Slide,” which was a film about a baseball player, oddly enough. Then came bit parts before his first leading role in 1930′s “Billy the Kid,” in which he played the title role (and was billed as “John Mack Brown”).

“He was in pictures with the biggest stars in the business,” film historian Richard Bann said. “I mean, he was in pictures with Lon Chaney Sr., Marion Davies, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford. He did several pictures with Greta Garbo. That’s a really big deal. He did a picture with Mary Pickford.”

The film Brown did with Pickford — known as “America’s Sweetheart” during the silent film era — was 1929′s “Coquette,” which happened to be Pickford’s first “talkie.” And it was the motion picture industry’s transition from silent film to sound that adds another twist to Brown’s movie career.

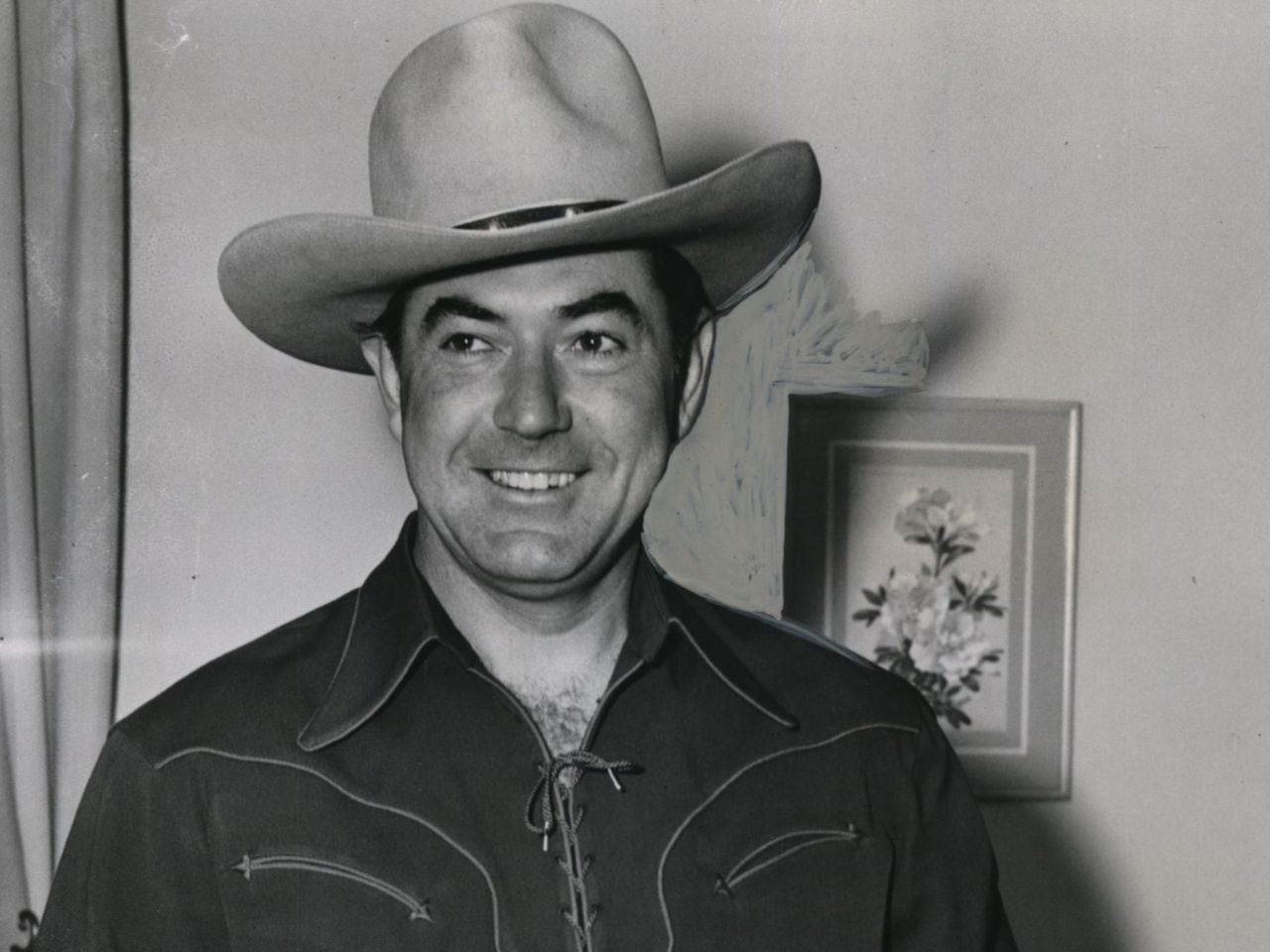

Johnny Mack Brown during his days as a Western movie idol. (Birmingham News file photo)Creg Stephenson/[email protected])

A son of the Deep South, Brown never had to worry about his Alabama accent during the silent film days. But once soundtracks were added, he no longer fit as a Hollywood leading man.

Brown was about three years older than another college football-player-turned-film-actor, John Wayne. Then known as Marion Morrison, Wayne had played football at USC in the late 1920s before a shoulder injury ended his athletic career.

Brown and Wayne both starred in big-budget westerns in 1930, Brown in “Billy The Kid” for MGM and Wayne in “The Big Trail” for Fox. Both were shot in a new widescreen format that made it very difficult for many moviegoers to see them (because not many theaters had converted to widescreen format), and both were considered career setbacks. (It wasn’t until “Star Wars” was released in 1977 that most theaters finally gave in and switched to wider screens.)

While Wayne bounced back with 1939′s “Wagon Train” and went on to become perhaps the most-famous actor of his generation, Brown was “demoted” to the B-movie ranks. Often shown as the second half of a double feature in theaters, B-movies were typically more low-budget than features or “A-movies.” (Brown also had the misfortune of starring alongside a young Clark Gable in 1931′s “The Secret Six,” and Gable “was blowing everyone off the screen” in those days, Bann said.)

Finding himself in ‘B’ movies

Picked up by Universal and later Monogram after being dropped by MGM, Brown was prolific in B-Westerns and serials, appearing in six films in 1934, seven in 1936, nine in 1937, eight in 1940, seven in 1942 and 10 in 1943, usually playing a strait-laced sheriff or U.S. Marshall. His most-popular character was Marshal Nevada Jack McKenzie, as whom he appeared 19 times from 1943-46.

Brown starred regularly in Westerns until transitioning into television roles in 1953, then came out of movie “retirement” for three films more than a decade later. His final film role came as Sheriff Ben Hall in 1965′s Apache Uprising.

Five members of the inaugural class of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1969 pose together. They are, from left, Johnny Mack Brown, Joe Louis, Paul “Bear” Bryant, Don Hutson, and Ralph “Shug” Jordan. (Birmingham News file photo by Robert Adams)Alabama Media Group

“From 1942-50, he was always in the Top 10 Western stars,” Bann said. “The Motion Picture Herald polled exhibitors to see ‘who are the draws, who is important?’ Johnny Mack Brown was always on that list for Westerns.

“He is one of the really important Western names. And I say his importance is proven by the fact that he stayed in this business and made approximately 200 pictures. He started at the top, OK, but he had the staying power. You don’t star in pictures of any strata — A or B class — unless you drive traffic to theaters.”

Because Brown’s B-Westerns and serials were typically shown on weekend afternoons, he was incredibly popular among children — his own included. Brown’s daughter Cynthia Brown Hale, now 84, recalled watching one of her father’s films along with brother John Lachlan (AKA “Lockie”) as a youngster in a crowded theater, when a humorous exchange took place.

“The movie is beginning to start and here comes this guy on a palomino (horse) racing towards the audience and this one little kid in front of my brother and I said ‘Oh, goody, goody, goody. Here comes my favorite cowboy, Roy Rogers,’” she recalled. “So my brother just sort of leaned forward and tapped the boy on the shoulder. He said ‘That’s not Roy Rogers, that’s Johnny Mack Brown.’ ‘No, no,’ the boy said, ‘that was Roy Rogers.’

“This went on and on and finally one of my friends up in about the seventh row, he got up and said ‘That’s not Roy Rogers, it’s Johnny Mack Brown. And he ought to know, it’s his father.”

Johnny Mack and Connie Brown had four children, oldest daughter Jane, then Locky, followed by Cynthia and youngest daughter Sally. All but Jane are still living, and often attend special events honoring their father, including the Johnny Mack Brown Western Film Festival in Dothan, which was held each year from 2009-19 (like many similar events, it never came back after the COVID pandemic).

A ‘grateful’ celebrity

Cynthia Brown Hale said she and her siblings were certainly aware of their father’s celebrity status growing up, though they’ve learned much more in the years since his retirement and death. And his football accolades were also something they came to know and appreciate as time went on.

The Browns regularly attended USC games over the years, though Johnny Mack always maintained his loyalty to Alabama. He was in the crowd at the Crimson Tide’s 1971 victory over the Trojans at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the game famous for introducing Alabama’s wishbone offense to the world.

“I recognized that he was a celebrity,” Hale said. “When he would go places, people would like to come up and shake his hand. When we would go to the football games — he always loved to go to the football games — there was always football fans that recognized him, you know, knew the Alabama story and all that kind of stuff. So it was always kind of fun to go out with him because everybody would come up and say hello.”

Johnny Mack Brown, Alabama Rose Bowl hero and Western movie idol, has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. (Photo illustration by Creg Stephenson/[email protected])Creg Stephenson/[email protected])

Brown received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960 — a symbol of his enduring popularity — and was posthumously awarded a “Golden Boot” in 2004 for his significant contributions to Western films. He was also mentioned in the 1941 novel “From Here to Eternity” (which later became an award-winning film) and in the aforementioned 1973 Statler Brothers song that name-checks him and dozens of other Western film stars.

Brown’s athletic accomplishments also draw accolades late in his life. In addition to induction into the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame in 1957, he was also part of the inaugural class of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1969 alongside such luminaries as Bryant, Auburn’s Ralph “Shug” Jordan and boxing legend Joe Louis.

Brown’s former coach, Wallace Wade, had to wait until 1970 for his own ASHOF induction. Speaking of Wade, he was once asked what he thought of Brown becoming a Western movie star. Wade remarked “well, he had to make a living somehow.”

Brown died from kidney failure on Nov. 14, 1974, at age 70. He is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, the same sprawling cemetery northeast of Hollywood that also serves as the final resting place of such legendary entertainers as Walt Disney, Michael Jackson, Elizabeth Taylor and Humphrey Bogart.

Brown once remarked that the best part of becoming a Western movie star was the opportunity to interact with his boyhood heroes. No doubt Brown himself was an inspiration to generations of youngsters, both fans of football and the movies.

“I’m sure he was very grateful for the life he lived,” Hale said of her father. “He was a modest man and a very kind person. He counted his blessings all the time.”

Special thanks to Brad Green of the Paul W. Bryant Museum and Tommy Ford, retired Alabama associate athletics director, for research assistance.

Creg Stephenson has worked for AL.com since 2010 and has covered college football for a variety of publications since 1994. Contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter/X at @CregStephenson.