Inside the Wisconsin youth prison where Nate Oats taught the Bible, played hoops and offered hope

In early February, almost three weeks after Alabama basketball player Darius Miles was arrested for capital murder, a local television reporter read a Bible verse to coach Nate Oats to preface a question during a news conference.

“Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance.”

Oats cracked a brief smile and later responded, “Was that James 1?”

For anyone who has known Oats over his 48 years, his accurately citing the Bible chapter and verse on the spot would come as little surprise. He is the son of Dr. Larry Oats, a Bible professor who has spent five decades in a variety of roles for Maranatha Baptist University in Wisconsin, including dean of the school’s baptist seminary.

It was at Maranatha as a student in the mid-1990s where Nate Oats’ faith and his love of basketball intersected on a daily basis, including during weekly trips to a youth prison that featured a mix of Bible study and pickup basketball games.

“I think what Nate and I tried to do is tell them, there’s hope,” said Steve Miller, who made the trips with Oats. “This isn’t the end of your road. You can fight back and get back on your feet. This doesn’t write your whole story. You can come back from this.”

And it was in Tuscaloosa more than 25 years later where those two aspects of Oats’ life converged again in the days and weeks following Miles’ arrest. Oats leaned more publicly on scripture in the wake of Miles being charged for his alleged role in the Jan. 15 murder of Jamea Harris, a 23-year old mother from Birmingham. Harris’ murder has brought national scrutiny to the program on top of the attention it would have received as Alabama ascended to becoming the No. 1 overall seed in the NCAA tournament.

A few days after Miles’ arrest, Oats read his team passages from the Old Testament story of Joseph, who was falsely imprisoned but maintained his faith and was eventually released.

Miles remains in the Tuscaloosa county jail, held without bail as he awaits a May 24 hearing. The six games Miles played early this season will be part of the team’s statistics and its story, which continues Friday evening in Louisville when Alabama meets San Diego State in the Sweet 16. By next week, the program could play in its first-ever Final Four.

“We’re having a blast,” Oats said Thursday. “We’re winning games. We know who we are. We’ve got a great group of guys that lean on each other, that have come close.

“We’ve never lost sight of the fact that we have a heartbreaking situation surrounding the program. The fact that we have such a good group of guys enables them to keep that, as they should, be a serious matter, and it has been, but you play basketball from the time you were young to get to these moments, and we’re going to enjoy these moments. They’ve earned the right to enjoy the moment they’re in, and I think our guys are having a lot of fun.”

Bible verses remain part of a wider array of quotes that Oats reads his team. Before one practice this week, Oats read his players Proverbs 27:17: “as iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.”

To understand Oats requires understanding how he was raised, and that was in the small city of Watertown, about halfway between Madison and Milwaukee. Oats’ father was two years into teaching locally at Maranatha when Nate was born in 1974. When Oats was four years old, he made a statement of faith and as a child learned to memorize Bible verses. But as he got older, Oats began to question some of his beliefs.

“I just had a lot of doubts, as I’m sure a lot of people really do at times,” Oats told Sports Spectrum in 2019. “At 16 years old, my sophomore year at high school, I really came face-to-face with God, really chose to dedicate my life to God, accepted him as my savior at that time. There’s a genuine peace that comes about you when you do that. … When I was 16, God definitely changed my life.”

Oats was about that age when his mother, Colleen, was diagnosed with breast cancer in her early 40s. The experience even made Larry Oats question his faith. Said Dr. Oats in a Maranatha-produced podcast last October: “I think it’s human nature. We look for some reason — why is this taking place? Why is this happening? It was a hard time, but we got through it. God was good.

“My wife’s one prayer when they discovered the breast cancer and how extensive it was, her one prayer was, ‘Lord, let me see my kids grow up.’”

Colleen Oats underwent chemotherapy and beat the disease, then beat it again in recent years.

The Oats family was involved in various Christian ministries in Wisconsin. Their church’s youth group made missionary trips to Mexico as well as Sturgeon Bay in northern Wisconsin, where the group ran a vacation bible school for a small church. Larry Oats traveled to preach at churches in need of a pastor, and Nate’s brother Andy worked church summer camps.

But basketball was a huge part of the Oats’ experience, too. Nate played in leagues around the Milwaukee area and traveled as far as northern Michigan to play in Gus Macker 3-on-3 tournaments. Both Nate and Andy played high school basketball and football, and it was during that time when they were first exposed to the Ethan Allen School for Boys, a juvenile detention facility about 30 minutes away in Delafield, a Milwaukee suburb.

The prison’s sports teams were part of the Oats’ high school conference, and their trips to Ethan Allen were like scenes ripped from the movie “The Longest Yard.”

“It’s a high-security facility,” Andy Oats said. “Walking into a prison with coiled barbed wire on the top of the fences — we had to go through a metal detector as an athlete, being restricted as to what you can bring in your bag. It was strange.”

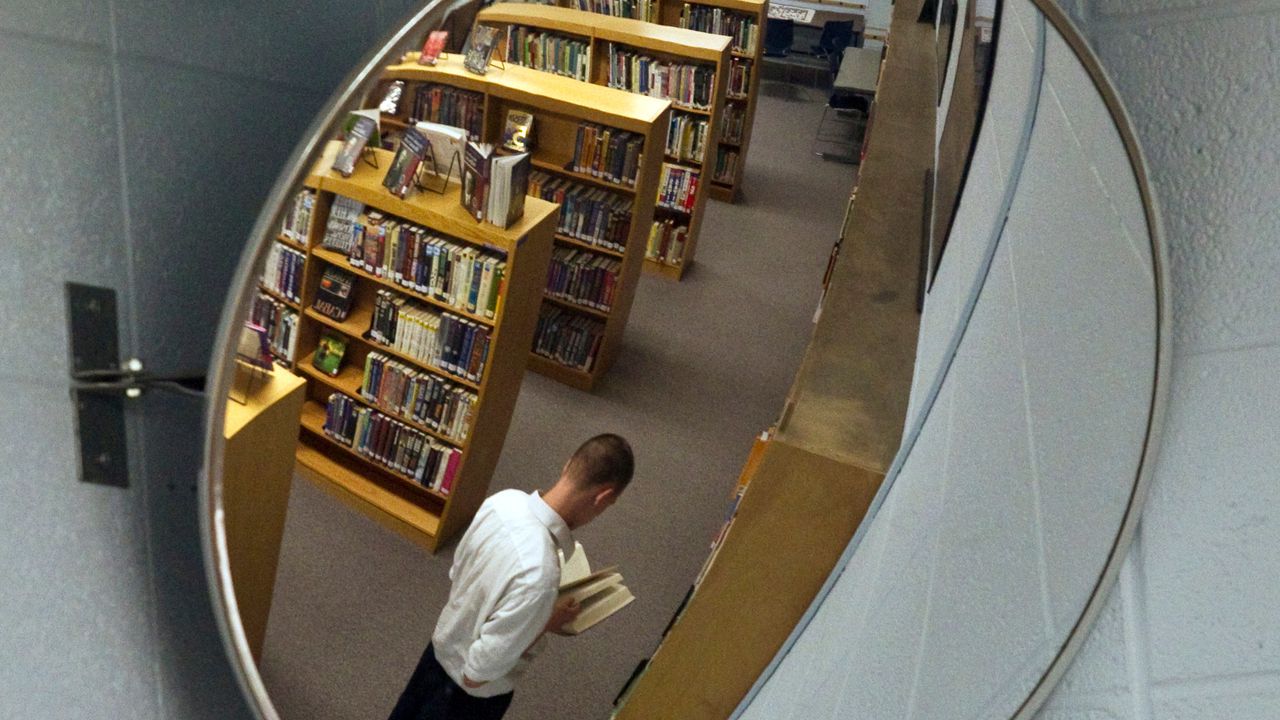

In this May 20, 2010 photo, a youth is seen in a mirror in the library at the Wisconsin Department of Corrections Ethan Allen School Thursday, May 20, 2010, in Wales, Wis. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)ASSOCIATED PRESS

The facility, which was eventually closed by the state in 2011, re-entered Nate Oats’ life when he was a student at Maranatha. Oats played on what was then an NCCAA basketball team and met Miller during open gym sessions. Although Miller did not play for the team, he loved basketball and had chosen to attend the Baptist college after turning his life around and discovering his faith at an Ohio boys home similar to Ethan Allen.

Miller became involved in Maranatha’s ministry trips to Ethan Allen and invited Oats to join him in 1997. After the 30-minute drive from Watertown, Oats and Miller walked through the familiar metal detectors and were placed in front of a room of 20-plus teenage offenders.

“And they would shut the door,” Miller recalled. “And you’re like, ‘OK.’”

The children housed in the facility liked to embellish the crimes that got them incarcerated, but Miller from his own experience in Ohio knew the offenses encompassed everything from shoplifting to murder. Not knowing how much the inmates knew about the Christian faith, Oats and Miller kept their Bible teachings simple, focusing on well-known verses such as John 3:16 and Romans 5:8.

“We tried not to preach at them,” Miller said. “We told them our testimony and then they’d ask us questions. We’d try to respond to them. A lot of them had hard backgrounds.”

The pair took questions from the audience — “Can you smoke weed if you’re Christian?” was one Miller recalls — and could offer different perspectives to the room. Oats was the clean-cut son of a preacher while Miller lived a more troubled childhood, but both sent the same message.

“Whether you come from my background or his background, we’re both sinners,” Miller said. “Regardless of what you’ve done to be in here, Jesus still loves you and there’s still forgiveness.”

Then, of course, came basketball. Oats and Miller headed to the yard and shot hoops with the kids in the prison. Whether it was on the court or in the room, Oats was able to connect with those in the jail.

“The thing about Nate when playing basketball with him, he has a unique ability — his intensity makes you rise to his intensity,” Miller explained. “When I would play with him, he would be intense and it would make me play harder or you would get hollered at, basically. You didn’t want that. So you would raise your intensity.

“But when we got into that room with those guys, I would speak and tell my story. Nate would tell his testimony and share a verse of scripture. He just has a way about him. They listen to him immediately. Not from authority, but just like, they listened. He had a way of speaking to them where they listened.”

A year earlier, Ethan Allen housed an inmate from Racine, Wisconsin named Caron Butler. A drug dealer in grade school, Butler was arrested 15 times by the time he was 15 and eventually spent 11 months in Ethan Allen. That included time in solitary confinement when he read Bible verses, which helped turn his life around after he was released in August 1996.

Butler later became the Big East player of the year at UConn and played 14 seasons in the NBA. Now 43, he has served as an assistant coach for the Miami Heat since 2020. Reached by AL.com through a Heat spokesman this week, Butler said he did not remember Oats or Miller, but their time at Ethan Allen was likely separated by only a few months.

Oats and Miller both wanted to follow up with the juveniles they mentored in Ethan Allen. Miller and his wife drove about an hour south to Kenosha, Wisconsin to bring one of them to church, and Miller and his family still live in Kenosha because of that.

“Our plan was not to just go there and teach them and then let them hang out when they get out,” Miller said. “Because that’s when most of them need most of the help. I know there were some kids from Milwaukee that Nate followed up with.

“That was just [Oats’] heart. He cared about those kids. And honestly, he cared about me and just my thing in that.”

Miller, who needed a job in college, got an assist from Oats, who was working as a roofer during his time at Maranatha.

“So I showed up at the job site,” Miller recalled. “He was up there with a pitchfork ripping shingles off. [The manager] said that Nate vouched for me. The guy said, ‘Alright, get up here.’ We roofed houses together for a while. Long, hard days in the sun. Then he would go back and keep working out [for basketball].”

Oats said during his 2019 podcast that he “wanted to be heavily involved in shaping kids’ lives” from the time he was a teenager, and that continued when he coached Romulus High School in Michigan from 2002-13. One of Oats’ former Romulus players, Valdez Green, told the Associated Press earlier this month that Oats’ family let him live with them after one of Green’s parents was murdered and the other was jailed. Oats’ service to his players was also detailed this month by the Washington Post.

“That’s just kind of how Nate is,” Andy Oats. “If he can help you, he’s going to.”

A bus for Maranatha Baptist University is parked outside Lucas Oil Stadium on March 4, 2023 during the NFL combine in Indianapolis. (Mike Rodak/AL.com)

The Oats family now lives in different parts of the country, including Nate in Tuscaloosa, his parents in Wisconsin and Andy in North Carolina, where he teaches math at High Point Christian Academy. Christmas gifts from Larry and Colleen to their children, which also include two daughters, are often Christian devotional books.

“They would still encourage us to read through it, kind of at the same pace as much as we could, either by text follow up with it or stuff like that,” Andy Oats said.

Nate Oats said he read the Bible in its entirety in 2018 as part of a group that included a high school friend and former college teammate.

“We just kind of said, ‘Hey let’s read through the Bible and let’s hold each other accountable.’ I did that,” he said during the 2019 podcast. “We made it through. You learn a lot, which is why I’d like to continue to do it where you’re in the Word every day and you are reading through the Bible on a yearly basis.

“God’s got a way to speaking to you when you’re reading then what you need at that time comes through. … You get reminded of stuff you haven’t heard for years.”

When Oats was hired at Alabama in 2019, he brought along Dr. Arnie Guin as director of player development and athletics culture. Guin, who holds a doctorate of ministry from Newburgh Theological Seminary, worked with Oats’ teams in Buffalo and was lead pastor at Cornerstone Church where Oats lived in Grand Island, New York. Oats’ Alabama teams have also been mentored by Scotty Hollins, a longtime chaplain for the athletic department.

Oats occasionally made reference to the Bible during his first three seasons at Alabama.

“I try to read the Bible every morning,” he said in March 2020. “I gave them a Bible verse … ‘Pride cometh before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall.’ I think it was applicable 3,000 years ago and it’s still applicable today. So let’s make sure we’re not overlooking anybody and we don’t have a spirit about us that we don’t have to bring an effort.”

But Miles’ arrest brought Oats’ faith back to the forefront. When Alabama played its next game at Vanderbilt, Oats read his team Romans 8:28, which reassures its readers about the good in any circumstance.

Oats also said he reached out to former NFL star Ray Lewis for advice on the situation. Oats called Lewis, “a man of faith as well” and said the two prayed together on the phone. Some questioned Oats’ conversation with Lewis, who was initially charged in 2000 with the murders of two men in Atlanta — but later reached a plea deal to testify against his two friends, who were later acquitted.

Oats has also faced criticism over the past two months for aspects of how he has handled Miles ‘ arrest and later news about star player Brandon Miller’s proximity to Miles the night of the murder. That has included Oats saying Miller was in the “wrong spot at the wrong time” that night — words for which Oats later apologized.

But for Oats, the game of basketball has always shared a prominent role in his life alongside his faith and desire to help those who are troubled. Miller, who said he arrived at Maranatha “messed up” after spending his senior year of high school in juvenile detention, can vouch for that.

“I came to college and tried to right all of my wrongs in my freshman year. I was really struggling,” Miller said. “Nate came to my room with his friends and asked me to play basketball. He said, ‘Will you please play on the team?’ My grades weren’t good enough and I just wasn’t in a place where I could.

“[Later] he said, ‘Why didn’t you play?’ I said I was dealing with my mental health, I couldn’t study. I just told him, I just physically couldn’t do it. He cared about me. He didn’t care if I was on the team or not — we had a good friendship. I think emotionally, I think he reaches out to a lot of guys that way.

“That goes back to faith. You care for people. You help people. I think that is part of who he is.”

Mike Rodak is an Alabama beat reporter for Alabama Media Group. Follow him on Twitter @mikerodak.