Hurricane Idaliaâs rapid rise is stirring climate concerns among experts. Hereâs what we know.

As Hurricane Idalia moves across Florida and north toward Charleston, S.C., there have been questions about how it was able to intensify so quickly. The low-pressure system started in the Caribbean Sea off Mexico then was upgraded to a tropical depression on Aug. 27. It grew into a major category four hurricane three days later with sustained windspeeds of 130mph.

It may break the record for how quickly it was able to intensify.

And it’s not the only unusual hurricane activity to hit the country in the past few weeks. Southern California was hit by Hurricane Hilary earlier this month, an infrequent occurrence. Hurricane Franklin, which did not make landfall in the U.S., is expected to run out of steam deep into the ordinarily frigid North Atlantic close to the southern tip of Greenland. Hurricanes don’t usually make it that far in cold water.

So, what’s going on?

Reckon spoke with Nan Walker, director of the Earth Scan Laboratory and professor at the LSU Department of Oceanography & Coastal Sciences, about how Idalia strengthened so quickly and other climate change issues caused by heat.

Reckon:

Even to an untrained observer of hurricanes like myself, Hurricane Idalia strengthened quickly. Why did that happen so unexpectedly?

Nan Walker:

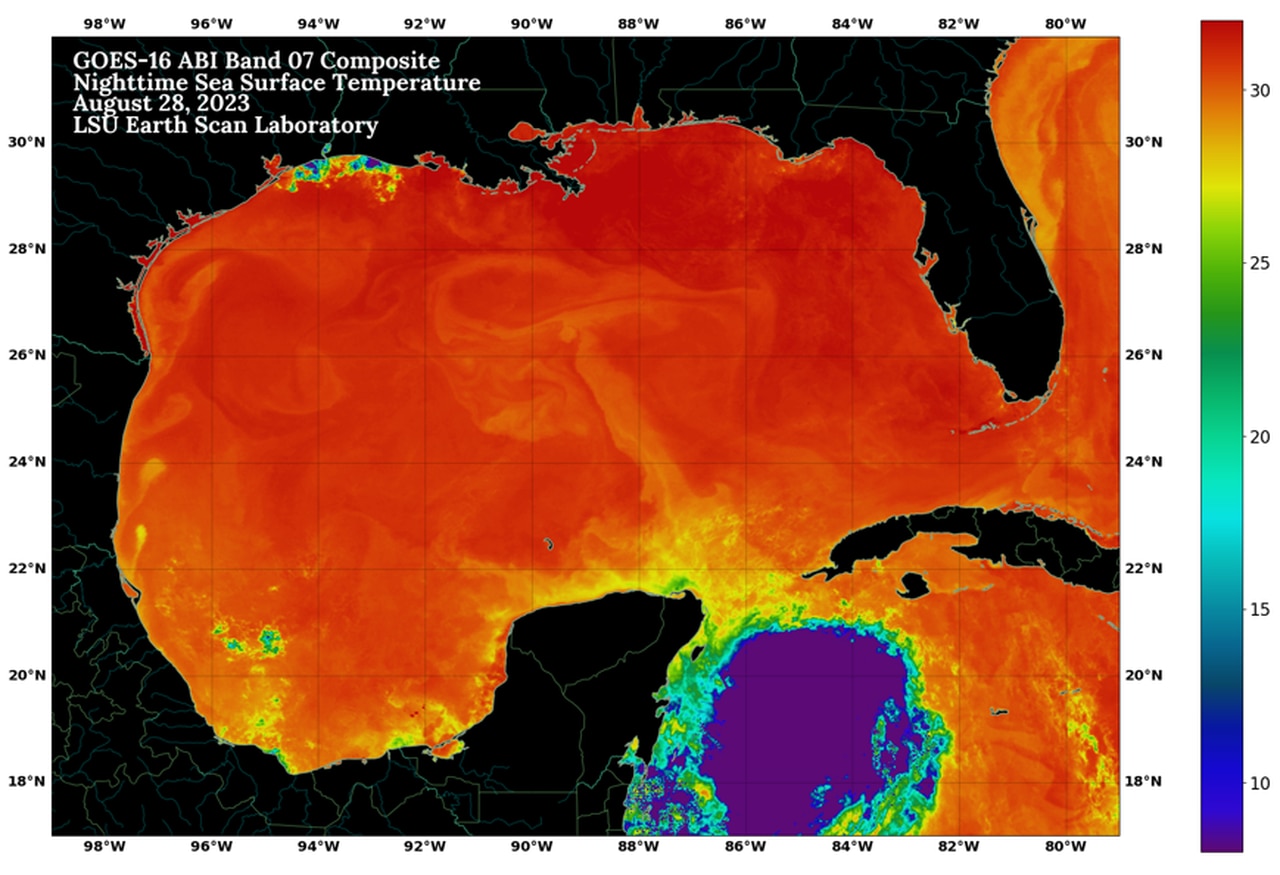

The Gulf is about 90 degrees right now, and warm temperatures, among other things, fuel hurricanes. The temperature where Hurricane Idalia formed in the Western Caribbean Sea is the highest in the whole North Atlantic right now. Hurricane Idalia formed in the Yucatan Channel, where some of the warmest waters exist, but that warm water also goes very deep. The Yucatan currents are 2,400 feet deep and introduce a huge amount of warm water into the Gulf, which helps hurricanes strengthen.

Can you help us visualize how much warm water is pumped into the Gulf?

I think many people have a concept of how big the New Orleans Superdome stadium is. The Yucatan currents force seven Superdomes of water into the Gulf every second. Over a day, it’s over 600,000 Superdomes. It’s one of the world’s biggest ocean current systems, and this warm water flux from the Gulf is happening continuously.

There’s been a lot of talk about how the El Nino climate pattern affects weather worldwide. How does it play into the unusual hurricane we saw on the West Coast, Hurricane Franklin out in the Atlantic, and now Idalia?

It’s been explained that when we have an El Nino in the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean, the hurricanes will be bad on the west coast and not as bad on the East, including in the Gulf. That’s because El Nino produces high westerly winds that are supposed to blow the top off hurricanes so they can’t develop. All of a sudden, that isn’t happening over the Gulf.

Month-to-month and season-to-season statistical analysis tells us what’s supposed to happen, but that can change very quickly on a day-to-day basis. Part of the reason we’re seeing unexpected conditions is because the Gulf is well beyond the temperature needed to support a hurricane. So, besides what happens with the El Nino, high heat can also make a difference. El Nino is one of the strongest fluctuations of temperature on the planet.

The gorilla in the room is off the coast of South America. On temperature maps, you’ll see big red areas that get very warm during an El Nino and produce conditions that can worsen the Pacific hurricane season than the Atlantic hurricane season.

Hurricane Ian made landfall on the west side of Florida in Sept. 2022. At the time, it was considered unusual. Hurricane Idalia also hit the west side. Are those occurrences unusual, and are the hurricanes attracted to that region’s warm, shallow waters?

It’s not as frequent that we get hurricanes on the western side of Florida. It usually means the hurricanes have to recurve quickly as they enter the Gulf. But this hurricane started in the Caribbean Sea, meaning it had a straight shot toward Florida. It also probably has to do with the average atmospheric currents, which are air circulation in the atmosphere. Those are also very important to how hurricanes behave.

The temperature of the Gulf of Mexico is much higher than in past years.

We’re told that high temperatures heat the water in the Gulf, and it stays warm for longer periods throughout the year. Is that contributing to more intense hurricanes?

It’s definitely a logical conclusion. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report categorically states that a warming world will be more conducive to stronger hurricanes. A majority of scientists agree with that statement.

This has been a very unusual summer over the North American continent, especially over Louisiana and the Southeast. We’ve had high pressure that has sat over us for weeks and months. It’s given us all this heat and drought.

The Gulf got very warm early this summer because of that high pressure, which means we didn’t have a lot of clouds. Clouds reflect radiation and prevent it from being absorbed by water. That means we had less humidity but more evaporation, which is how hurricanes begin to form. So, logically, more heat means more hurricanes, even though atmospheric conditions also play a huge part.

In 2020, we had the most active hurricane season in history, and some experts said this would be the future. But the last two years have been a lot less active. People who don’t believe in climate change have used those two years to dismiss climate change. How does one respond to them?

Some powerful hurricanes over the last two years have caused extreme amounts of damage. 2021 was very active, even though many storms didn’t last long. That’s still important. Anyone who observes the weather must know that a lot can change from year to year. There’s also a lot of variability in the atmosphere, and as much as scientists try and predict, it’s still very much a challenge.

The butterfly effect is a good example of how things can change easily and quickly. In some conditions, a very small turbulence factor, as small as a butterfly, might influence the weather if all the conditions are favorable.

I also wanted to ask you about Hurricane Franklin, which is moving north through the Atlantic. It’s predicted to run out of steam not far off Canada’s Newfoundland coast and the southern tip of Greenland, partially in the Arctic Circle. How common is it for hurricanes to travel that far in the North Atlantic?

Franklin has shocked me. It’s very unusual. I think the sea surface temperatures in that area are slightly warmer than normal but not warm enough to support a hurricane. There’s not a lot of heat in the ocean up there compared to the Gulf, Bahamas, or the coast of Florida.

Atmospheric circulation is also helping it sustain.

Another reason is it overlaps with the Gulf Stream. There are also some latency effects like it takes a while to spin down once it becomes a hurricane. Usually, that would mean hitting cold water or land. Anything that cuts it off from its source of warm water.

Overall, Franklin is a little bit surprising to me. It’s also possible the prediction isn’t going to hold. We’ll see where it ends up.

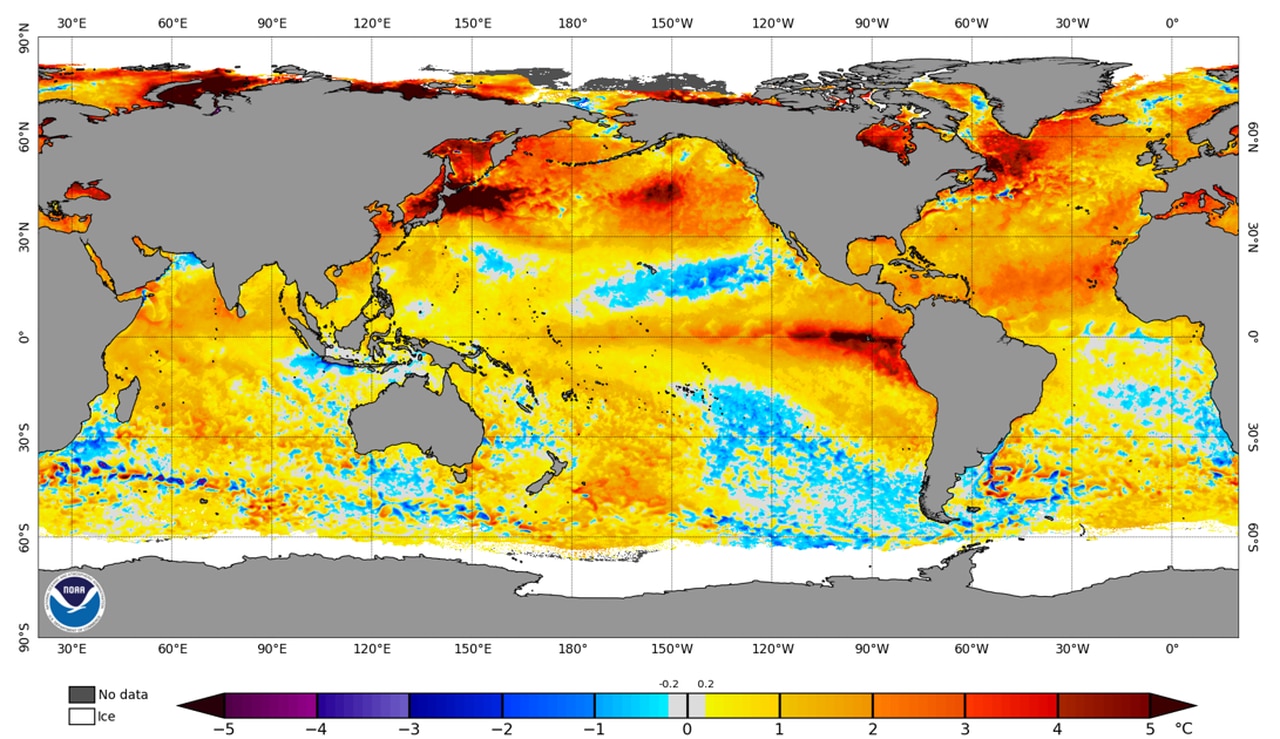

The image shows where global water temperatures have increased the most over the last 30 years. The higher latitudes, where ice and permafrost are located, are warming the most.

You’ve mentioned heat quite a bit. How is that affecting other parts of our climate aside from hurricanes?

Most alarmingly, there is a climate change problem in the high latitudes, where the ice is melting. That can help CO2 and methane build up in the air. But you have to look at the patterns. What are the long-term patterns to understand what’s going on? When we have warming at the poles or in the high latitudes, that decreases the change in temperature from the tropics to the poles, leading to extremes in weather, which is what we’ve been seeing.

It’s interesting to see that we’re having these huge anomalies in the high latitudes, which is consistent with these extreme events we’ve been experiencing, like all the wildfires, droughts, and extreme temperatures. And we’re seeing that across the whole central U.S. up to Iowa. High-pressure systems over the central U.S. are unusual for summer.

Once the ice melts, it’s very unlikely that we will get it back. The ice caps reflect solar radiation, which helps to keep our planet cool. There are also huge areas of melting permafrost in Alaska. If that happens, methane is going to be released. Methane is about 30 times stronger as a greenhouse gas than CO2.