How Kay Ivey is muscling up Alabama’s executive branch

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey vanquished eight GOP opponents during last year’s primary and didn’t even have to sweat a runoff.

She enjoys strong approval ratings, is a Morning Consult Top 10 governor, and is a lame duck who does not have to worry about future political races.

“The governor is very popular,” said state Senator Sam Givhan, R-Huntsville. “She has a big stick, and she knows how to use it.”

But questions loom over how influential Ivey’s office will be on weighty decisions about pandemic relief funds, tax cuts, and other fiscal issues that can divide a Republican-controlled state government.

Separately, her administration is attempting to sway the Alabama State Supreme Court that her administration should be granted “executive privilege” to determine what kind of documents the executive branch should be required to release.

The issues in Alabama are not unlike what other states and their legislative and judicial branches face as governors in Florida, Texas and beyond test the boundaries on constitutional separations of power.

It’s a power grab move, some say, for some governors who saw their authority expand thanks to emergency powers exhibited during the onset of the pandemic in 2020.

“State legislatures have been fighting back for the past two years and have reclaimed much of their policy making and budgetary authority,” said Thad Kousser, professor of political science at the University of California-San Diego, and author of the 2012 book, “The Power of American Governors: Winning on Budgets and Losing on Policy.”

“But governors have grown comfortable testing the bounds of their formal powers and I think we’ll continue to see more examples of assertions of executive authority – which will be tested in the courts and by legislators – in the years to come,” he said.

Executive privilege

Ivey has signaled she is willing to flex her executive muscles, and she hopes the Alabama State Supreme Court will back her. The governor is asking the high court to grant her administration executive privilege from releasing text messages between her current and past chiefs of staff and the director of the Alabama Department of Transportation.

The text messages sought are part of an ongoing litigation over the fate of a $52 million coastal bridge project.

“She is a lame duck, and the fact that she has to be sensitive to public opinion is less than before now,” said Jess Brown, a retired political science professor at Athens State University and a longtime observer of state politics. “But the politics is such that the public favors transparency. If she’s seen as a governor that is using some legal doctrine to keep the public from knowing what is the public’s business, then that is not going to play well politically.”

Ivey’s administration is not doing anything that governors elsewhere have not already tried. In Washington and Oklahoma, state supreme courts granted their governor’s executive privilege.

Other governors are pushing the courts for similar powers.

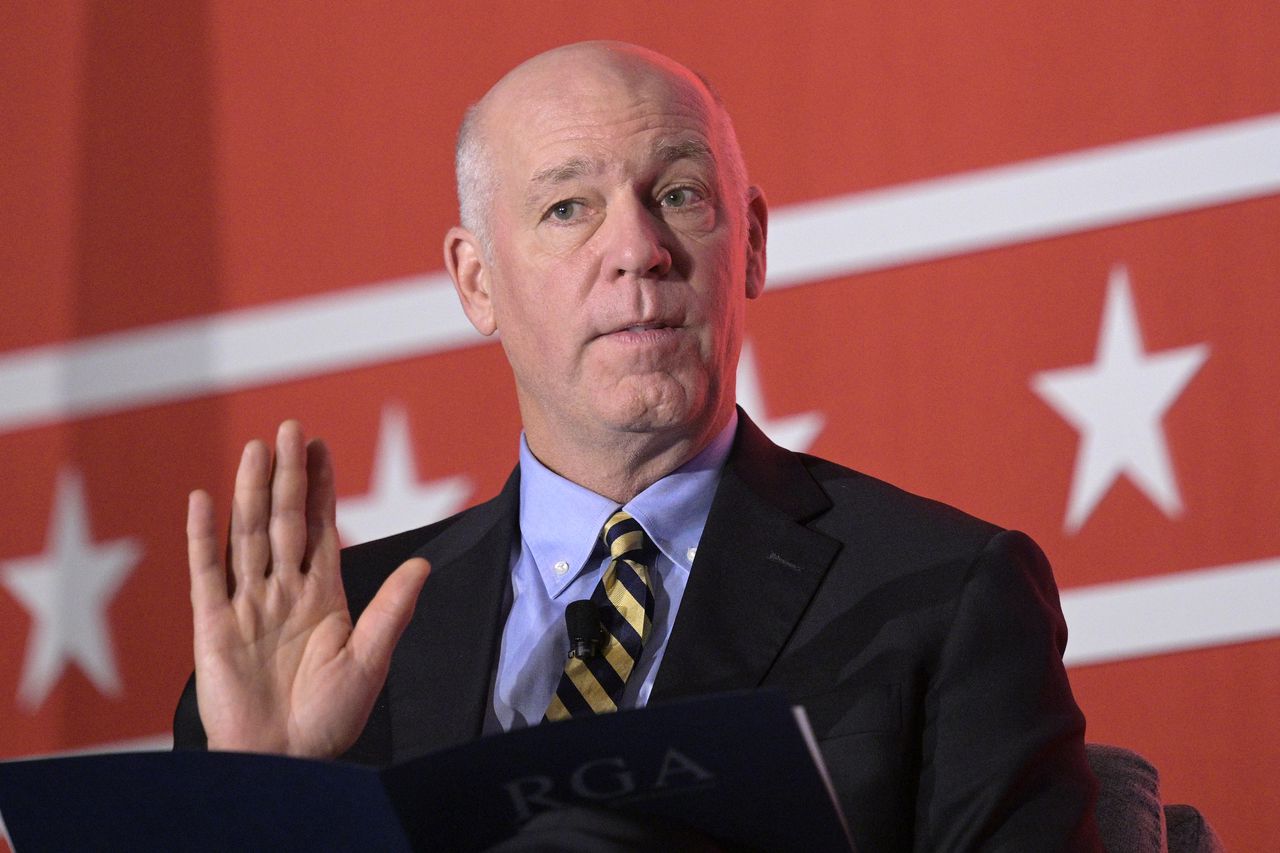

Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte poses a question while taking part in a panel discussion during a Republican Governors Association conference, Wednesday, Nov. 16, 2022, in Orlando, Fla. (AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack)AP

In Montana, Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte argued last year that deliberations within his administration are part of the “deliberative process” and should be exempt from the state’s open records law.

A district judge in Montana ruled in December that Gianforte’s administration needs to turn over emails and other records pertaining to state legislation. The judge ruled that granting broad executive privilege to Gianforte would “effectively gut” the right to know as it applies to the executive branch, according to media reports.

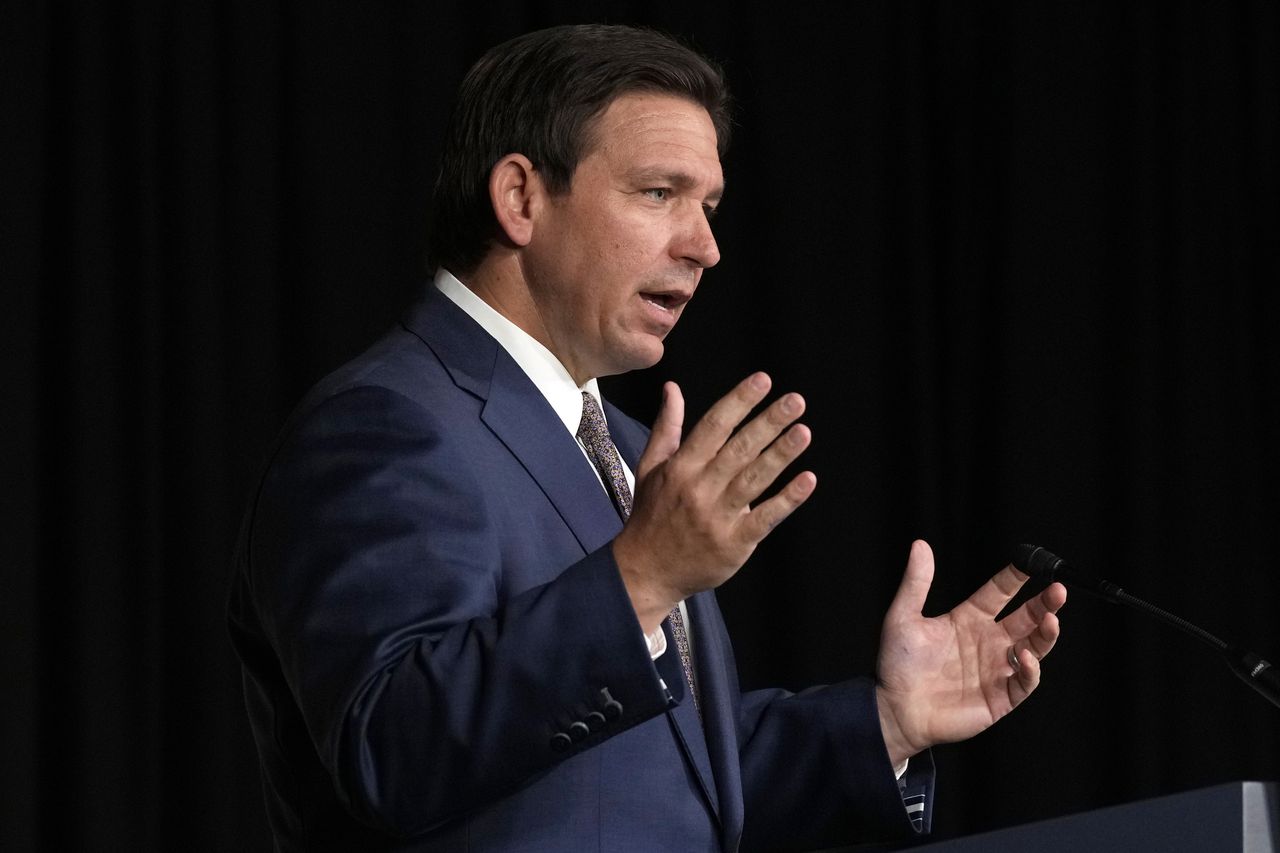

FILE – Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis speaks, Feb. 15, 2023, at Palm Beach Atlantic University in West Palm Beach, Fla. Gov. DeSantis has signed a bill to give himself control of Walt Disney World’s self-governing district, punishing the company over its opposition to the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law. The bill requires DeSantis, a Republican, to appoint a five-member board to oversee the government services that the Disney district provides in its sprawling theme park properties in Florida. The governor signed the legislation on Monday, Feb. 27, 2023. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee, file)

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis – who is eying a 2024 presidential run – wants to keep confidential the candid conversations he had with anonymous “legal conservative heavyweights” over a Florida State Supreme Court appointment, and he is pursuing executive privilege.

Legal arguments against the governors point to the lack of executive privilege spelled out in state constitutions.

But the same can be said about the U.S. Constitution, which does not mention nor include a road map for presidential executive privilege. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled during the Watergate era in favor of executive privilege as a consequence of having a separation of powers among the branches of government. Presidents now use executive privilege to information from the courts, Congress, and the public to protect the confidentiality of the office and its decision-making process on national security matters, among other issues.

Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and an expert in Southern politics, said even in Alabama’s enormous state Constitution consisting of over 370,000 words, there is no mention of “executive privilege” that would keep Ivey from providing the information sought in the coastal bridge case.

“It’s the longest Constitution in the country and there is no language on executive privilege,” Jillson said. “I think the courts would assume you don’t have it. Ivey is claiming the President has it and since ‘I’m the chief executive in Alabama, I surely should have executive privilege as well.’”

He added, “In 240 years of Alabama history, I am not aware of governors making that claim.”

Legislative relationships

Outside the courtroom, Ivey’s power will loom over the legislative session where Republicans, many of whom are friendly to the governor, hold a supermajority status.

The governor is angling for state lawmakers to approve her administration’s proposals on how to spend approximately $1 billion in pandemic relief funds.

She called a special session during her State of the State Address earlier this month to deal with the state’s portion of the American Rescue Plan Act money. The Alabama House, by a 102-3 vote Tuesday, endorsed much of the same plan the governor’s office backs, allocating funding for health care reimbursements, water and sewer infrastructure and broadband expansion. The Senate could vote on it today, or early next week.

A more pronounced showdown could come later this spring when lawmakers consider whether to back Ivey’s pitch for doling out rebate checks in the amount of $400 per taxpayer, $800 for a family.

An alternative plan to cut the state sales tax assessed on grocery purchases, could muscle out the rebate talks. A plan was unveiled earlier this week that would phase out the state’s sales tax on essential foods like milk, eggs, cheese, fruits, vegetables, whole grain bread, canned tuna, cereal, and infant formula.

“The governor has ways to get what she wants,” said Givhan, who acknowledged there was little appetite for pursuing rebate checks without a more robust conversation about permanent tax cuts that have been backed by conservative think tanks like the Alabama Policy Institute.

Gina Maiola, a spokeswoman for the governor, said Ivey is confident the Legislature will have productive special and regular sessions, and will work well with the legislative bodies.

“The governor very much values her relationship with the Legislature and looks forward to continuing that as we move into the regular session,” Maiola said.

Ivey has a history of getting legislators behind proposals she wants – most notably the state gas tax increase in 2019 to support road and bridge construction projects.

Governor Kay Ivey waves to guest after she is sworn in as the 54th Governor of Alabama during a ceremony on the steps of the Alabama State Capital Monday, Jan. 16, 2023 in Montgomery, Ala.. (AP Photo/Butch Dill)AP

Two of the legislators who are part of the current state budget deliberations say there will be no rubber stamps. They also say there is a healthy push-and-pull between the legislative and executive branches.

“I would classify it as healthy antagonism,” said state Senator Greg Albritton, R-Atmore, who chairs the Senate General Fund committee. “It has gone back and forth based on personalities, but the issues have been very similar.”

He added, “There is a healthy discussion between executive and legislative bodies over most issues. There is a cautious respect between us. And I think that is what it should be about in government.”

State Rep. Rex Reynolds, R-Huntsville, agrees and said he feels there “is a healthy balance” between the two branches.

“Do we always agree?” Reynolds said. “No, we don’t. The House has 105 members. It’s a deliberative body.”

Political blowback

Some of the more experienced lawmakers might be keeping early tabs on whether any of the GOP newcomers to the legislature will be willing to break away from the governor’s office, and support initiatives she might not necessarily back.

The House and Senate began the special session with two dozen new Republicans in the Alabama House, many of whom gave a quick nod to the pandemic relief plan.

“We’re sending hundreds of millions of dollars to (state) agencies, and (individual lawmakers) have little to no input except for that one time when we appropriate,” said state Senator Chris Elliott, R-Daphne.

Elliott has found himself on the other side of the governor’s ire before. In 2019, shortly after the crumbling of a prior iteration of the Interstate 10 Mobile River Bridge and Bayway project, Ivey removed Elliott from a transportation committee, replacing him with a Democratic senator. Elliott, at the time, was a critic of that version of the I-10 project, which was backed by the Ivey administration.

“The governor’s office and ALDOT director decide where the priorities are,” said Elliott, referring to decisions throughout Alabama over how state tax money is spent on road projects. “I’m not saying that is good or bad, but the power rests in the governor’s office. That’s where the decisions are made.”

Said Elliott, “It’s clear that the governor has the juice.”

Others who have challenged Ivey’s authority have faced political setbacks. Most notable was former state Senator Thomas Whatley, R-Auburn, who lost a close primary election last year to former Auburn City Councilman Jay Hovey.

Whatley pitched a bill in 2021, that would have curbed a governor’s authority during states of emergency. The governor has the power to declare a 60-day state of emergency without input from the Legislature.

The legislation did not advance and was not supported by the governor’s office.

Elliott said he doubts a similar measure will return.

“I do see a (hesitancy) to really challenge this governor in particular,” he said. “In all fairness, this is the only (governor) I’ve worked with in my role with the Legislature. Historically, though, and looking back, there was more push and pull between the governor’s office and the legislature.”

Governor authority

Longtime political observers agree, but to a point. They note that by way of tradition, the governor is considered relatively “weak” compared to executives in other states. The office, for instance, does not have authority to appoint legislative committee chairs, or the speaker of the house.

The lieutenant governor, a position that runs alongside a governor in some states and akin to a vice president, is a separately elected position in Alabama.

Alabama only requires a simple majority of the legislature to override a governor’s veto, while most states – Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, for example – require a two-thirds majority.

Past governors have struggled to outdo their legislatures largely because the chambers were more split politically. Since 2010, the Alabama Legislature has been a supermajority Republican, and all constitutional officers have also been represented by the GOP.

In this June 28,1968 file photo, presidential candidate, former Alabama Gov. George Wallace arrives in Boston. (AP Photo, File)AP

An exception was Gov. George Wallace, whose tenure in the governor’s office elevated his national profile and presidential ambitions.

“He was an overwhelmingly powerful governor,” said Steve Flowers, a former Alabama state lawmaker and author of the book, “Of Goats & Governors.”

“When I was in the legislature, he totally controlled it,” he added. “He picked the Speaker of the House and made the (legislative) committee assignments. I was on the Rules Committee, but it was just a rubber stamp (vote for Wallace’s assignments).”

Phillip Rawls, a retired journalism professor at Auburn University and a former longtime journalist who covered Alabama state politics for The Associated Press, said a Wallace-backed speaker would often appoint Wallace loyalists to head up each legislative committee.

“Wallace also used his loyal campaign network to hinder the re-election campaigns of legislative incumbents who didn’t support him,” Rawls said.

But Flowers said Wallace never attempted to utilize the courts to keep public documents from the public view.

Ivey’s executive privilege filing before the Supreme Court came shortly after she signed in January an executive order for state agencies to respond to request for public records. Maiola then said last month that while the governor wants to make the request process timely and fees for public records more reasonable, she also acknowledges there has to be a balance “for an efficiently run government.”

“Wallace would never do any heavy-handed stuff like that,” Flowers said, referring to shielding public records. “But he was in an era when the press, during a slow news day, would ask him, ‘Why give the road contracts to your friends and cronies?’”

Wallace, Flowers recalled, would respond, “Who should I give them to? My enemies?”