How Alabama can help save dying butterflies

Butterflies are iconic North American insects that are rapidly declining in population, and scientists are looking at Alabama for help in finding out why.

Problem is, few Alabamians know about this. Time is ticking on a pilot program that expires on November 1, and a federal agency is hoping Alabama teachers preparing for the 2023-2024 school year will consider participating as part of a community science initiative.

The overall scope is simple: Have students collect dead butterflies, moths, and skippers, and forward those collections to a federal agency.

The collection, scientists say, could reveal crucial information as to why the insects are dying and could unlock keys on how to eventually save them. According to researchers, the populations to a majority of 450 butterfly species are dropping by nearly 2% every year since the late 1970s.

Related: Federal agency wants dead butterflies from Alabama: Here’s why

“We cannot answer research questions without collections like this,” said Julie Dietze, the scientists in charge of the project with the U.S. Geological Survey, the federal agency coordinating the pilot program. “It gets people talking about insects. They don’t get talked about a lot.”

She added, “Kids participating in sending samples that become part of the U.S. Geological Survey’s scientific collection is a really cool project. They are helping us. The moth or butterfly they send might have a contaminant in there … and every specimen matters. And there is no collection that exists, to my knowledge, within the U.S. where the citizens are sending in butterflies and moths.”

Why Alabama?

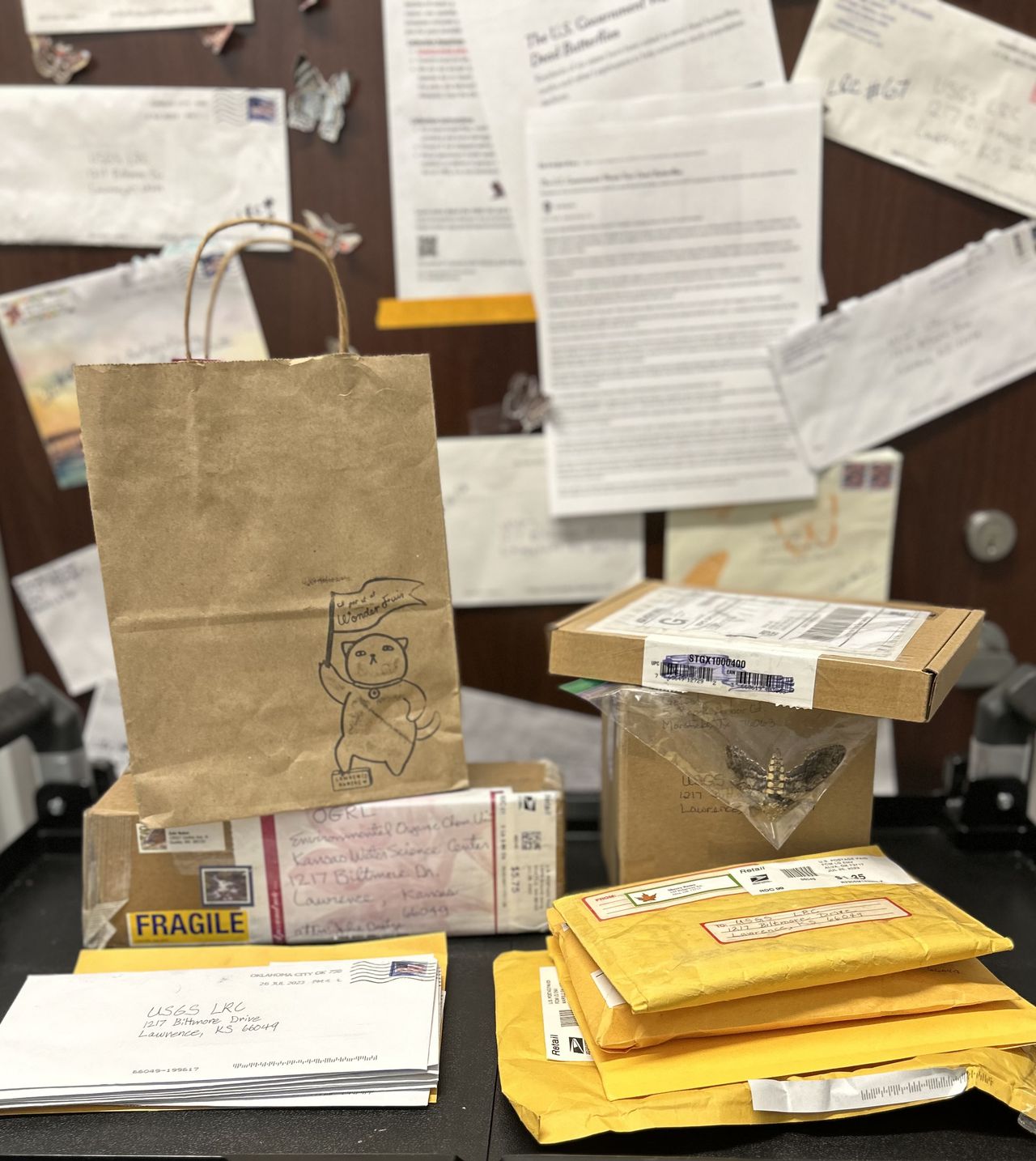

Specimens received on July 31st for the Lepidoptera Research Collection. (photo by Rachel Buccieri, submitted by Julie Dietze with the U.S. Geological Survey).

Alabama is one of only six states chosen to participate in the pilot, which began in April. The others are Texas, Georgia, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska.

“I think it’s great,” said Todd Stuery, associate professor of wildlife ecology at Auburn University. “Many butterflies are declining in numbers, and yet typically don’t get as much attention from scientists as more charismatic megafauna (bigger animals). Scientists are increasingly turning to citizens to help collect large-scale scientific data, and this is a great example of that.”

Dietze said the states were chosen based on having at least one of three factors: They are located along the Monarch butterfly’s migration pathway, near the Corn Belt, or have a large presence of Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) – commonly referred to as “factory farms.”

“The states up North are Corn Belt areas with high pesticide use, (but Alabama has) a high presence of (CAFOs),” Dietze said. “While they are spread throughout the U.S., Alabama has a high number of broiler chicken confined animal feeding operations.”

CAFOs produce large volumes of waste that are contaminated with pesticides that pose direct threats to butterflies, according to the Washington, D.C. non-profit Center for Food Safety.

Dietze said that so far in Alabama, few specimens have been turned in. She said there has been an uptick of specimens submitted from other states following recent national publicity including an article about the work in a recent edition of The New York Times.

“We just haven’t received a lot yet from Alabama,” Dietze said. “I think people, if they hear about it, I think they will (participate).”

She said she is willing to set up a virtual classroom visit to discuss the project in hopes of getting schools on board.

“I think this collection is useful for us and other scientists now and if we can get enough (dead butterflies, moths and skippers), we can build this up and use them 20 years from now to compare for differences (in specimens).”

Troubling trends

FILE – Monarch butterflies land on branches at Monarch Grove Sanctuary in Pacific Grove, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 10, 2021. On Thursday, July 21, 2022, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature said migrating monarch butterflies have moved closer to extinction in the past decade – prompting scientists to officially designate them as “endangered.” (AP Photo/Nic Coury, File)AP

The collection comes at a time when researchers and government agencies are trying to raise the alarm over declining insect populations, particularly the migratory monarch that experiences a metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly. Less than 1% of the western monarch population remains, while the eastern monarch population has fallen as much as 90%.

Monarch butterflies were officially designated as an endangered species one year ago by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Studies suggest the decline has multiple factors, including the loss of habitat in the forests where the insects winter each year.

Monarchs also require a vast, healthy migratory path and large forests for survival through the winter months. But the butterflies are running up against a reduction of their habitat in the U.S. due to herbicide applications, land use changes, forest degradation, extreme weather conditions and climate change.

“Butterfly declines, as well as insect declines more broadly, are of significant concern as part of the biodiversity and climate change dual crisis,” said Emma Pelton, senior endangered species conversation biologist and Western Monarch Lead with Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. The Oregon-based non-profit that has partnered in recent years with university researchers to address questions about widespread pesticide contamination of milkweed, a plant critical to a monarch butterfly’s survival.

“There’s much more to do to increase our understanding of declines, and also, we know enough to act now,” Pelton said.

Awareness campaigns

Indeed, awareness campaigns are occurring nationwide, including the National Wildlife Federation’s “Mayor’s Monarch Pledge.” The pledge commits cities toward restoring monarch habitats at parks and green spaces.

From 2015-2020, more than 600 mayors in the U.S. signed the pledge, but only three are in Alabama: Mountain Brook, Priceville, and Fairhope.

The Xerces Society is also encouraging people to simply snap photos of an insect and upload it to the iNaturalist app. Other actions include planting native lants and reducing the use of pesticides on gardens.

“Planting native milkweed and nectar plants helps not just monarchs but also many other species as we start to ‘rewild’ our urban, suburban, roadside, and agricultural areas,” Pelton said.

Lawmakers are also looking to increase federal funding toward conservation efforts. Democratic California U.S. Rep. Jimmy Panetta is pushing for congressional passage of the Monarch Action, Recovery, and Conservation Habitat (MONARCH) Act. The legislation is aimed at adding federal funds toward supporting preservation, protection, and restoration of natural habitats of the western monarch butterfly.

Federal funding is increasing for butterfly conservation. The federal funding package approved late last year included $10 million – up from $4 million the previous fiscal year – for butterfly conservation. Of that, $3 million was made available through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 to establish the Monarch and Pollinator Highway Program. That program promotes pollinator-friendly practices on roadsides and highway rights-of-way that includes planting and seeding of native grasses, wildflowers, and milkweed.

Some of the efforts are paying off as the western monarch, which declined to a historic low population of 2,000 butterflies in 2020, rebounded to more than 247,000 in 2021.

How you can participate

Send dead butterflies, moths and skippers collected in Alabama to the following address:

USGS LRC, 1217 Biltmore Drive, Lawrence, KS 66049

What should be sent?

- Insects must be already dead. In other words, don’t kill a butterfly or moth to send it in.

- Insects be larger than 2 inches.

This Mitchell’s satyr, a federally endangered species of butterfly, was discovered in Bibb County, Alabama in 2000 when the species was not known to live within 500 miles of the site.Jeffrey Glassberg/North American Butterfly Association

- Protected species under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Endangered Species Act aren’t accepted. That applies to only the Mitchell’s satyr Butterfly, found in Alabama.

How to mail in the specimen?

- Put dead butterflies, moths, and/or skippers inside a resealable plastic bag. It is OK to combine and send damaged or not fully intact specimen.

- Freeze if not shipped within three days to aid preservation.

- Place specimens inside sealed envelope with proper postage affixed and place in a mailbox. It is not necessary to include a return address label or any other information.