How âThe Color Purpleâ is giving reproductive justice a platform bigger than any award

As the future of abortion access and bodily autonomy remains unsettled, the media is depicting our concerns on screen. Forty-nine abortion storylines played out on television last year, new podcasts are centering abortion, and we’re even seeing revivals of classics bringing forth the conversation in innovative ways.

Nominations for the 96th Academy Awards were announced this morning. Though the original movie received 11 nominations, it infamously walked away without winning in a single category. This year, Danielle Brooks is nominated in the Best Supporting Actress category for her role as Sofia.

Last year’s “The Color Purple” is an adaptation of the broadway show, which like the 1985 “Color Purple” film, are based on Alice Walker’s 1982 book. From high school American Literature classes to references in hip-hop – like Kendrick Lamar’s inclusion of the iconic line “all my life I had to fight” on the 2015 single “Alright” – The Color Purple is a pillar of both Black and American culture.

Key elements of all renditions of the story are similar, revolving around the story of Celie, a young Black girl growing up in early 1900′s Georgia. We watch Celie birth the child of her abusive father (who we later find out is her stepfather), have the baby taken away, be ripped from her only pillar of love – her younger sister Nettie – and continue to be abused by Mister, an older man she’s forced to marry. All of these occur against her will, through the choices of men in her life. Celie undergoes traumatic sexual, physical and mental abuse but over the decades, perseveres, finds herself and spoiler alert: finds her sister.

“From start to finish, it touches on so many critical issues for reproductive justice,” Dr. Regina Davis Moss, president and CEO of In Our Own Voice, said of both “The Color Purple” book and movies, mentioning the adultification of Black girls, sexual violence, and having children taken away as a few key points.

Reproductive freedom is especially threatened in Black communities. The maternal mortality rates for Black women are almost three times higher than the rate for white women, Black women have less access to contraception, and face a higher likelihood of incarceration, which we’ve seen by the criminalization of Brittany Watts. Because of these factors, which are just a few of the many disparities faced, it’s especially important to explore the framework of reproductive justice through an intersectional lens.

Celie is a dark-skinned Black woman in the South, she’s poor, she’s queer, and she comes from an abusive upbringing. All these elements of her identity factor into the choices she makes and how she’s viewed and treated by others – a truth that spans into how Black individuals are treated today.

“Black girls are normalized to survive. But that’s because of gender oppression and racism and classism and that’s what intersectionality is about: how this is unique, but also how they’re all exacerbated by each other.” said Davis Moss.

A major difference between this version and Spielberg’s film is that this one is a musical. Throughout the narrative, characters burst into numbers that help them express the emotions of their scenes – from Shug confronting her estranged father to the excitement of Celie finally finding her passion and opening a business, told through the power of Fantasia Barrino’s vocals– It’s uplifting. It even sparked movement in real life from actress Taraji P. Henson, who played Shug Avery, to speak out about the gender pay gap and unfair treatment of Black actresses in Hollywood while on the press run to promote the movie’s release.

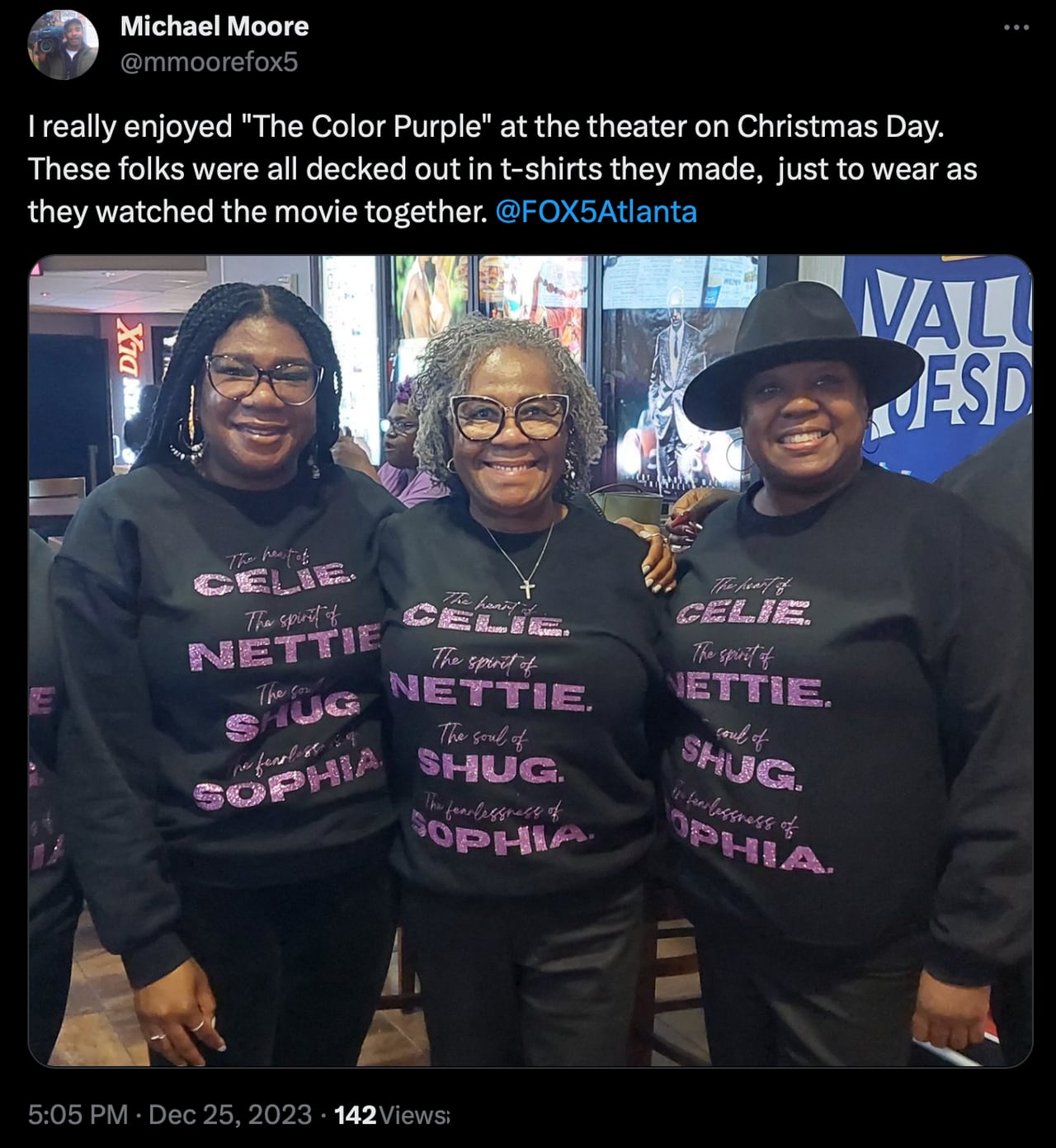

The energy of the movie was visible for many who watched the movie in theaters, with many on social media sharing tweets about the strong reaction from crowds.

Watching the latest rendition of “The Color Purple” in theaters was a bonding experience for many.@mmoorefox5

Writer Nylah Burton explained in Vox the communal experience many Black women had at movie theaters watching this film.

“It was a diverse crowd, but the people who clearly knew the lines — and, more importantly, felt the lines — were pretty much all Black, and most of them were women,” wrote Burton.

The movie saw a 65% Black audience opening weekend, according to the New York Times. Davis Moss said that she watched the film in theaters with generations of Black women. Her group, and others, clapped and cheered along in the scene where Celie gathers up the courage to stand up to Mister and tells him that she’s leaving.

“It’s the story that we hear all the time around the kitchen tables, at our family gatherings, or we get on the phone and we get a call that one of our sisters or cousins or aunts or nieces is in trouble,” she explained. “We mobilize, and so that’s what you’re seeing is knowing that at the end of the day, we’ve got each other’s backs.”

While a story of sisterhood, a major theme which was not as emphasized in the initial film is queerness. Celie develops a crush and then sexual relationship with Shug, her husband’s mistress who she befriends. Celie, for what seems like the first time, finds an outlet for pleasure and the empowerment she gains from this relationship pushes her on a path towards self discovery, which eventually prompts her to leave the abusive household.

“Shug teaches Celie to love herself and own her sexuality. Growing up, I was repeatedly told that good sexual experiences were defined by marriage and love. Through Celie’s story, we see that marriage does not necessarily equate to good sex and that love is not present in all marriages,” Nicole Gathany wrote in a 2020 “What The Color Purple Taught Me About Sexual Freedom” blog post for Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity.

The right to enjoy sex and remove the connection between sexual pleasure and reproduction is a core value in the reproductive justice framework, as developed by Sister Song.

“In my mind, that is really another way that they’re centering intersectionality in the film,” said Davis Moss. “Alice Walker was unapologetic about having relationships with them [women] and believing that women could love women and we could love men, but she also believed that came from a place of empowerment and celebration.”

The movie was called a source of Black healing last month by NBC reporter Char Adams. What stands out about Celie’s character arc is the lack of outside source of “white savior” to lead her to a happy ending. It is through the Black women in her circle that teach Celie how to love, respect and stand up for herself, which she becomes self empowered. It’s a testament to the ongoing work in Black communities to empower their own.

“That movie was about resilience and advancement and tenacity and coming to self sufficiency despite all of the systemic and structural things that she [Celie] was facing,” said Davis Moss. “…That is also the larger point which we say about reproductive justice: you don’t move along this path without us. When you’re talking about us, then we should be at the table, right?”