How âFreedom Teachingâ schools educators on dismantling anti-DEI bans with radical hope, joy and imagination

With more than half of the United States implementing bans on anti-racism efforts in some form or fashion, educator and activist Matthew Kincaid has laid out a strategy that can serve teachers in countering the assault on diversity.

In his book “Freedom Teaching,” Kincaid explores how defunding diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, whitewashing Black history curriculums and attacks on critical race theory takes a toll on Black and brown students. But the book also empowers teachers, administrators, parents and others to awaken “the movement within you,” as he states in the beginning of his book, with tools to dismantle the systemic racism operating within and outside school systems.

Kincaid survived these systems as a Black student attending predominantly white schools lacking in cultural competency. Chapter one of his book opens with a memory of a white child prohibiting him from playing in the sandbox with his white classmates. The white teacher didn’t intervene, Kincaid wrote, leading to an isolating experience on the playground that his mother later made sense of by giving him “The Talk.” The one all Black parents dread when they look into a Black child’s eyes to educate them about navigating a skin color-coded world without absorbing its hatred.

Kindcaid doesn’t want Black and brown students and anti-racists to feel powerless against the pedagogy of white supremacy. He saw those same systems in play as a middle school social studies teacher and administrator in New Orleans. As the son of parents who went to segregated schools and the grandson of a sharecropper, Kincaid took pride in creating an educational environment where the expression of his students’ Blackness was celebrated and encouraged as they empowered themselves through learning.

“I wanted my classroom to be an oasis. I wanted my classroom to be a safe haven,” Kincaid said. “I wanted my classroom to be a space where we could come together, laugh and have fun and learn in a way that centered the positive experiences that come with acquiring knowledge.”

Kincaid took his mission to create anti-racists school environments a step further in 2016 by becoming the founder and CEO of Overcoming Racism, an organization that has hosted race and equity training with over 100 school systems across the country as well as businesses. Advocating for an education system that benefits all students is an urgent need in a field known as “the great equalizer of the conditions of men.” On Jan. 24, the same day “Freedom Teaching” published, the governing body over Florida’s public universities voted to prohibit the use of state and federal funding on diversity, equity and inclusion efforts on campuses. This is a result of a DEI ban Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law last year, replicating a tactic more than 20 other states have either implemented or considered in 2023.

Writing “Freedom Teaching” was a matter of accessibility and educational responsibility, Kincaid said. He realized not everyone can get to an anti-racism workshop, especially when those bans infiltrate K-12 education. While Overcoming Racism saw a record-high interest in DEI education and strategy training in 2020 and 2021, Kincaid said some schools systems and other organizations have scaled back or completely eliminated the racial justice and equity work that was previously implemented in response to anti-DEI policies.

“I think, especially now, in a time period in which teachers are under fire for doing what’s right by kids, this book can provide an additional support for anyone who wants to engage in culturally-responsive practices in their classrooms, but their school system maybe would never bring someone like me to actually come give a presentation,” Kincaid said.

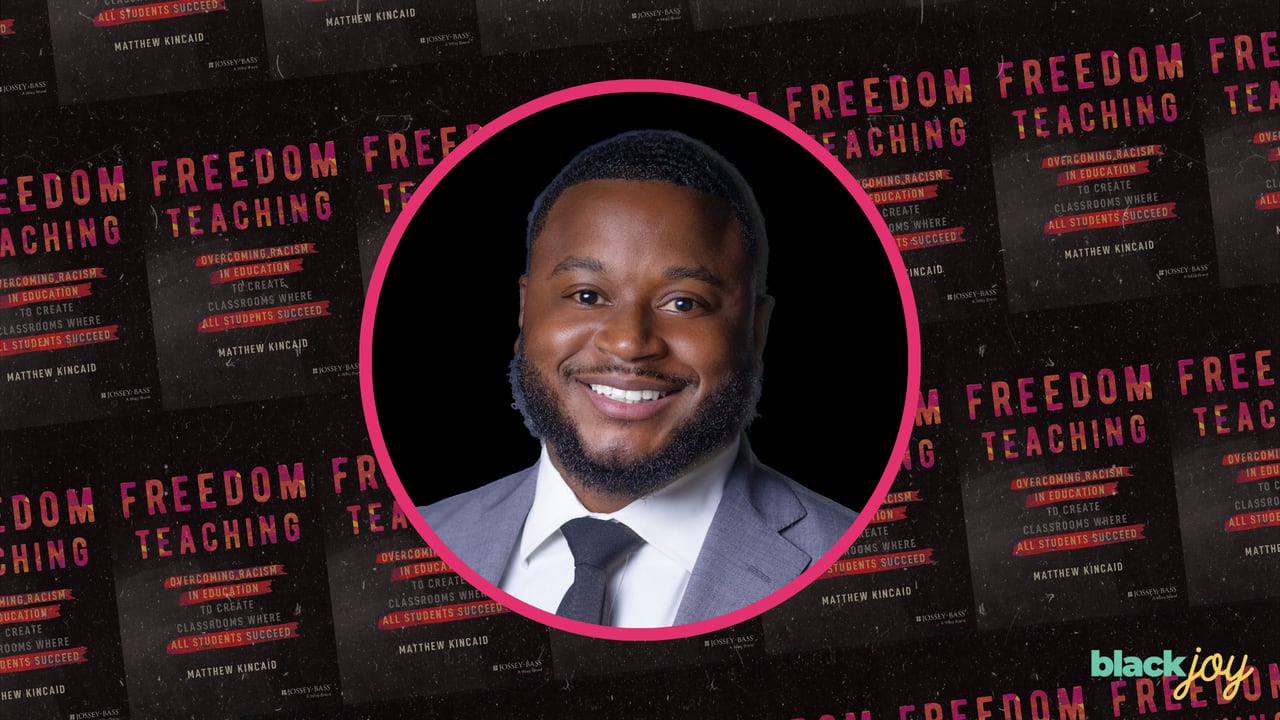

Matthew Kincaid wrote the book ‘Freedom Teaching” to help educators during the bans on diversity, equity and inclusion.Ian J. Solomon

With a portrait of civil rights leader and Georgia representative John Lewis behind him, Kincaid talks to Black Joy about how teachers can make “good trouble” in the classroom, why radical imagination and hope are essential in the freedom teaching framework and his favorite moments of Black joy during his time in New Orleans.

Starr: Can you talk about how education and activism intersect with one another?

Kincaid: I believe that education, in a lot of ways, is a form of activism because we know, and historical trends have proven, that our education system has failed large groups of students consistently. I think that oftentimes, people try to make it seem like students from certain communities are somehow less intelligent, less ambitious or less equipped with the skills that are necessary to contribute to society. That couldn’t be further from the truth, and the people who are trying to proliferate those myths are people who have never stepped foot in these communities and have never stepped foot in the schools.

In New Orleans, I met some of the most thoughtful, curious, intelligent and innovative students I’ve ever had a chance to be around. So if the school system is failing them, then that is an indication to me that the system is broken, not the young people who are in it. To me, what activism is, is working to fix systems and to make the system that exists around the people who are in them worthy of the people who are in them. So whether it’s founding Overcoming Racism, my job in the classroom or now writing the book “Freedom Teaching,” I’m trying desperately to create an education system deserving of the amazing students currently existing in these systems.

Can you break down the meaning of “freedom teaching” and how it helps students?

Freedom teaching is any deliberate act that enhances the freedom of children, both inside and outside the classroom. I used to tell my kids that their education would open doors and provide choice for them. I didn’t want to create a dynamic in my classroom where I was like, ‘You will do this. You will do that.’ I wanted students to have access to choice. Did I want my kids to go to college? Absolutely. But could a student make a decision that college maybe wasn’t best for them and they want to go on an alternative route? Of course they could. And I wouldn’t want them to view that as a failure. But I never wanted them to not go to college because they didn’t have the choice to or because they didn’t have the grades, the test scores or whatever.

And so I think about freedom as a proxy for choices. And the environments that many of us grew up in the socioeconomic structures that many of us grew up in, the racial categories many of us grew up in oftentimes limits our freedom, and as a consequence of that limits our choices. We have less choices over critical aspects of our lives like what you’re going to eat for dinner that night, whether or not it is nutritious, where you’re going to live, whether or not that place is safe, where your kids go to school, whether or not there’s a quality education here. All of these things are what we pretend in the United States of America everyone has equal access to. But the reality is that some people have the choice to send their kids to school where they want to, go to the doctor where they want to, live wherever they want to, eat whatever they want to and other people don’t have those choices at all.

And so freedom teaching is about enhancing the freedom of children so that we can enhance the choices that young people are able to navigate throughout the course of their life.

What makes freedom teaching so important to implement right now?

In the United States, we think about freedom very much through an individualistic lens. ‘Don’t trample on my freedoms.’ You know, rugged individualism and pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. And it doesn’t really matter how many people you step on while you’re on your way to success. As long as you make it there, the means will justify the ends.

But for communities of color, and for any targeted community in this country, freedom has always been a shared trait. Whether or not we could vote was something that was shared. Whether or not we can eat in certain restaurants was something that was shared. Whether or not we could go to whatever schools we wanted to go to was something that was shared. So we looked at freedom as a means of saying, ‘How can we create classrooms where students recognize that by freeing myself through my education, in providing myself and more choices to my education, I can also work to free the people to the right and to my left. The more free the student is over here, the more free the students are over there, the more free I am as well. So now, I’m not just accountable to myself. I’m accountable to this entire classroom community because our freedoms are intertwined.’

And I think in the United States, if more of us understood that our freedoms were intertwined, we wouldn’t do things like fight against critical race theory, against diversity, equity, inclusion, or fighting against women’s reproductive rights or fight against everyone having the ability to access health care, or access to early childhood learning or whatever. Because you start to realize that instead of me being in competition with the next person, that person’s success also helps to elevate me. That is a principle I tried to inspire in my classroom, and that principle is the through line throughout the book.

I actually noticed how you talked about the importance of student power in the classroom in your book. It helped me to realize that there are power dynamics in play in the school system. Teachers are over students. Administration is over teachers and so on. How does student power lead to liberation?

Power and control are illusions. I think power is best when it is shared. I think that if you believe you can control another human being, then you’re probably going to be leaning into principles and practices that are not effective in classrooms. My goal was always to find ways to cede power to students because students cede power to us. And what I mean by that is that if the students ever, in mass, decided that they weren’t going to do what their teachers wanted them to do, there’s nothing as an educator you could do about that because they significantly outnumber us.

If the power that we have in the classroom is given to us freely given by students, and they’re trusting us to use that power in ways that help to further their education, then it’s our job also to give power back to kids. And so now we’re doing something in relationship with one another, instead of doing something where I am doing something to you. I just personally believe that students come into schools with knowledge and skills and passions and hopes and desires. We will be silly to not capitalize on those and to treat them like they’re just some robot in a seat that you’re supposed to program to know certain things. Kids have all of this worth and value that they bring into our classrooms. And so many teachers in this country don’t know how to leverage that.

Since you started Overcome Racism almost 10 years ago, I was wondering if you could talk about the enthusiasm for anti-racism instruction in 2020 versus what you are seeing now in 2023 and 2024 with book bans and policies against DEI? What do you think led to this shift?

I think the shift has everything to do with the patterns of progress and regression that have always existed in this country. Every moment of significant progress for people of color, but specifically people who are Black, is always met with a moment of significant regression. In the case of 2020, it wasn’t even a moment of significant progress. It just was a moment of perceived progress. A moment of collective calling for progress. So the problem is that those of us who view ourselves as antiracist, for whatever reason, we consistently find ourselves getting caught flat-footed not understanding that every time we call for equity and justice, that the establishment is going to have an equal and opposite force or pressure pushing back on that progress or those calls for progress.

Emancipation Proclamation frees enslaved Black people. You have Reconstruction — 10 years where Black folks are being voted into political office and having access to institutions that they never had access to before. And then the racial backlash comes in the form of Jim Crow, Black Codes, and racialized terrorism…And then you have 2020, when people saw the tragic killing of George Floyd, calls for racial justice and business and corporations all stamping their flags into Black Lives mattering. Now we see Black history being banned in schools. We see students facing significant punitive structures for the way their hair grows out of their head.

It’s night and day between what is going on in 2023 and 2024 versus 2020 in a lot of ways. It’s extremely devastating because as a people we have fought so hard. I look at John Lewis behind me. And I think about all the things that he fought for only for him to pass away in a version of America that was actively working to slide back into white supremacy in a very public way. I think a lot of the white people who are being miseducated to believe that antiracism, affirmative action or any policies that support communities of color are somehow racist against them have no literacy around the idea of how long it took for us to even get a foot in the door. My parents went to segregated schools. My grandfather was a sharecropper. The things I’m doing are things that the people who came before me couldn’t do. You would hope that when I have kids they will grow up in a society where they would have more rights and more freedoms than what I had. But we’re actually seeing more regressive policy around civil rights and around race today than we have in the last 30 years so I can’t guarantee that.

Doing this work in the midst of this kind of aggression is hard, but it’s just a reminder that the reason why people push back so forcefully against our work is because it’s effective. And so it’s just a reminder that we have to keep going.

That leads to my next question about an important aspect you pointed out in your book, which is radical hope and radical imagination. Why was that included in your freedom teaching framework?

I think one of the things white supremacy does a really good job of is that it steals our imagination – is that it steals our imagination, is the ability to imagine a society in which Black people, and people of color more broadly, are equal or exist in an equitable structure as people who are white. It tries to be a thief of joy and then also, a thief of hope.

So when I’m talking about radical hope, it’s about saying, ‘We can’t get to a destination where schools actually work for Black and brown kids if we don’t believe that this is a possibility.’ I think most of the “reforms” that have been thrown at fixing schools are implemented without a real belief that we can actually say, ‘Yeah, we can slowly improve things.’ We’ll say that we believe that one day those kids will be on the same level as these kids. But the inputs we’re putting into our school system will never have that output because children of color aren’t going to schools that affirm who they are and where they come from in the same way that white children go to schools that do just that.

When I was in school, I read ‘The Great Gatsby.’ I read Shakespeare and I had a whole history class on European history, feudalism and all these different systems and structures. I can imagine as a white kid, when you sit down to take that test and all of the stories, words and authors are people who look like you and came from places where you might have come from, I can imagine why education can feel like something that is in alignment. I also can imagine and understand why for Black and brown kids that’s not the case.

We talk about the word radical a lot in the book. People make the word radical out to be this horrible word. If you’re a radical, you’re a bad person. But if you look at synonyms to radical you find words like ‘thorough.’ We find words like ‘complete,’ you find words like ‘root’ and ‘branch.’ And so we need hope that is complete. We need hope that it’s thorough. We need hope that we can pull up the roots of the system and build something new and effective. Radical hope, in a lot of ways, is a precursor to everything else that the book talks about because if you don’t believe, then you’re wasting your time by trying to implement change.

I noticed while reading the book myself that you used Rosa Parks as an example of radical hope. As an Alabamian myself, I have to ask what made you choose her?

So I am obsessed with the story of Rosa Parks because there are so many mis-tellings of who she is and what she did. She is quite possibly the most famous civil rights activist in the history of this country. If she’s not the most famous, then she’s in the top three. And yet and still, there is not one consensus story on the history of what she did.

If I had just believed what my books told me about Rosa Parks – that she was a tired seamstress who was just too tired to sit on the bus. Or if I believe the other narrative: the story which was like ‘No, Rosa Parks wasn’t a tired seamstress. She was an activist who went to the Highlander Folk School and she studied the practices of nonviolence and it was intentional that she sat on the bus and was arrested.’ But then even that isn’t the full story. Ten years before that, she was fighting for justice for Recy Taylor as well as other women who had experienced sexual violence. She created the Committee for Equal Justice.

For so many people who are involved in activism, we have heard these mistold stories of the singular activists who did this one thing and then poof, change happened. And I think many of us like to expect change to happen that way now because that’s how we’re told. We put ourselves out there to make the change, and when things don’t change we get distraught. We turn to despair. We get burned out and we quit.

Of course because of who we are I have to ask if you could share a moment of Black joy in the classroom with us!

I think I’m biased because I taught in New Orleans, but New Orleans feels very much like an epicenter of black joy. The students found ways to be joyous whether they were roasting each other, banging on desks making music, playing in a heated basketball game outside in the courtyard or they’re playing music in their band class. Joy seemed to emanate out of the young people that I worked with.

Spirit week was a time during our homerooms. All of our home rooms were named after colleges and my homeroom was Howard University. And we were the Bison. We had chants, and we had cheers and we had this attitude of like, ‘You know we are unstoppable.’ We went into every spirit week competition determined that we were going to be the homeroom that was crowned at the end of it.

Another memory that particularly sticks out to me is that I had two kids in my classroom. One of which was on the autism spectrum and because of that, a brilliant, amazing, thoughtful, awesome kid, but like middle schoolers, you know, this kid is a little bit different. So they may not fully understand him. And there was a young lady who was very popular, but also very tough. No one messed with her and she spoke her mind. It did not matter if it was a peer or a teacher. So in a lot of ways, these two students are, on the external, polar opposites. I have this theory that if they got to know each other, they would form a bond. And so I put these two students in the front of the class. I set them next to one another. And the first couple of weeks were a little rocky in terms of them feeling each other out and understanding nuances.

But by the end of the school year, you better not mess with the student who was autistic because the young lady who I sat next to him was coming for you. She had built a very strong relationship with him, and they had the most beautiful relationship where they were, like I said, polar opposites, but she got his jokes and he was able to help her with some of her work. She would stand up for him, and because other kids saw her having a relationship with him, they started to give him a chance. And then before I know it, my whole homeroom is defensive over this kid.

To me, as a teacher there’s nothing that makes you happier than when your ‘kids’ get along and love one another even for the nuances that we are bringing to these spaces.