He’s been on death row for decades. Alabama ‘downplays’ DNA that points to someone else, judge says

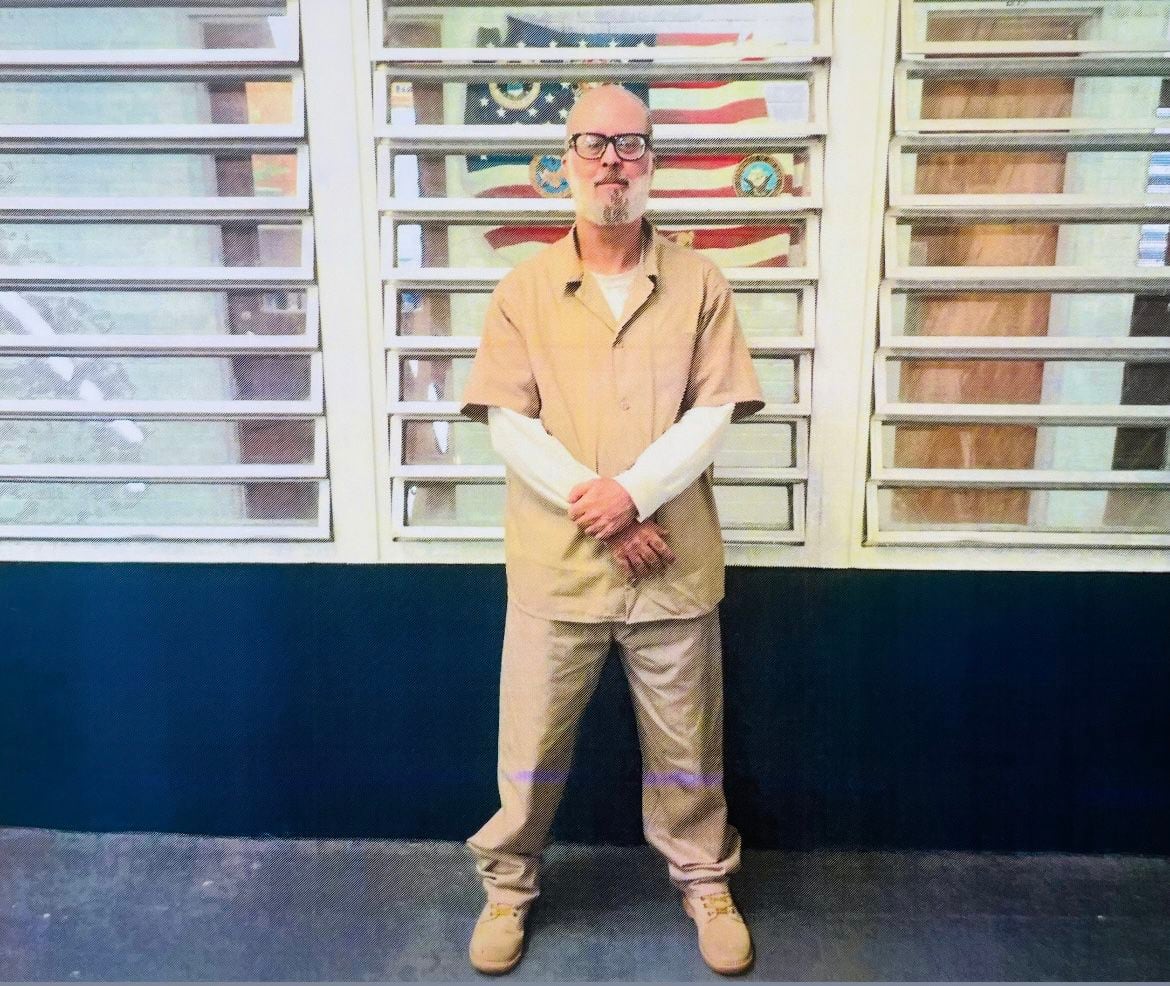

For most of his life, Christopher Barbour has been waiting to die.

He’s grown old behind bars, spending more than thirty years on Alabama Death Row for the brutal slaying and rape of a Montgomery woman in 1992. No physical evidence tied him to the case, but he confessed to the killing shortly after.

Yet ever since, he’s maintained his innocence, asking for someone to believe that police coerced him into confessing to a crime he did not commit.

And now, a federal judge is listening.

Earlier this year, U.S. District Judge Emily Marks allowed Barbour’s innocence claim to go forward, setting a conference for Oct. 9 to hammer out next steps.

Her reason?

The DNA pointed to someone else.

In 2023, according to court records, new DNA testing was done in the case of Thelma Roberts, a mother of two who was found raped, strangled and stabbed in her Montgomery home more than three decades ago.

The new testing showed the man who raped Roberts didn’t match Barbour, nor the other homeless man who he pointed to as an accomplice in his controversial confession.

Instead it was someone who Roberts knew, someone who lived across the street and was friends with her children.

But when authorities looked for Jerry Tyrone Jackson, they didn’t find him living across the street anymore. Instead, by 2023, they found Jackson already living in an Alabama prison, sentenced to life for fatally stabbing a different woman in a different part of the state after she refused his sexual advances.

The DNA from Jackson “is powerful evidence that Barbour’s confession is false,” Judge Marks wrote in an August 2024 order, “and that Mrs. Roberts’ murder did not occur as the prosecution presented it at trial.”

The judge allowed the case to proceed — the first ever federal habeas lawsuit allowed to go forward in Alabama under what’s called an ‘actual innocence’ claim.

“It is still more likely than not that no reasonable jury would convict Barbour based on the new DNA evidence,” she wrote.

“And unlike people, DNA doesn’t lie.”

The crime

It was the spring of 1992. Thelma Roberts lived on Manley Drive, in Montgomery’s Chisholm neighborhood, with her two teenage children. The 40-year-old was married, but she and her husband were separated and he didn’t live in the family home. She went to church often, didn’t drink or smoke, and wasn’t dating, according to her family. She worked as a housekeeper at the hospital on Maxwell Air Force Base.

Christopher Barbour has spent more than thirty years on Alabama Death Row for the murder and rape of Thelma Roberts, a Montgomery woman, in 1992. Roberts lived at this home on Manley Drive, in Montgomery’s Chisholm neighborhood. Tamika Moore | AL.com

Across town, Christopher Barbour was 22, grappling with the death of his mother, who had recently died by suicide. He was homeless, with court records describing him as living in a wooded area behind the Eastdale Mall. He had briefly lived with his grandfather but had recently been kicked out of the house for not following his rules.

By all accounts, Barbour didn’t know the Roberts family.

Back in Chisholm, on March 20, 1992, Roberts’ two children met up with some friends after school, including their neighbor Jerry Tyrone Jackson. Jackson was 16 at the time, and the Roberts kids were 16 and 17.

According to court records, the night started when the Roberts teens went to another friend’s house around the corner, on Amanda Lane. The two Roberts kids stayed the night, leaving their mother at home alone. There were several other teens and preteens, including Jackson, at the house on Amanda Lane.

Things started off rocky. According to court testimony, the host of the party said Jackson exposed himself to a 13-year-old girl, and the girl ran home. The host was upset because she didn’t want to get in trouble — her mother had banned Jackson from the house after he was rumored to have “went through the window with a screwdriver and raped” a girl who lived nearby, she testified in 2023.

Jackson was arrested for rape in the late 1980s, according to his own deposition. Court records don’t reflect how the case ended, because Jackson was a juvenile at the time.

At some point after exposing himself to the young girl that night, the teens all said in depositions and affidavits filed in the federal lawsuit, Jackson left the party. He returned at some point later that night to ask for a cigarette, before leaving again. He didn’t stay the night.

The next morning, the Roberts teens walked home, unlocked the door and found their mother dead on the bedroom floor.

The initial investigation

According to federal court records, investigators determined Thelma Roberts was murdered sometime during the night on March 20 or in the early-morning hours of March 21, 1992. She was found at about 11 a.m., when her son went inside her bedroom.

Police didn’t find signs of forced entry, and the Roberts kids maintained the door was locked when they got home.

Investigators from the police and fire departments wrote in their notes, scanned in court records, that Roberts had been burned. Soot, ashes and “partially burned materials” were found throughout the house.

An autopsy later revealed Roberts died from nine stab wounds in her chest, but she also had been raped, strangled and beaten. A butcher knife from the kitchen was left protruding from her chest, and there was a plastic bag over her head when her kids found her body. The victim’s 17-year-old son took off the bag and removed the knife before police arrived.

Several small fires had been started in the house, police notes showed, using paper and clothes. The flames had failed to catch, but the assailant ripped the smoke detector from the wall and left it in the house.

The fires, though small, would play a pivotal role in the investigation. Fire officials were already looking for the person, or people, who were starting small fires at Winn-Dixie stores across the city. In those blazes, someone would use paper goods to set a fire on one of the aisles. Then, another person would steal items, using the fires as a distraction to run out the front door.

Almost immediately, police zeroed in on Roberts’ estranged husband, Melvin Roberts, as a suspect in the murder. Melvin Roberts said in a 2022 deposition that he was handcuffed to a chair at the police station for 12 hours and that one detective kicked him in the chest. “…they kept on terrorizing me,” he said. “Kept on terrorizing me until I told them I was going to talk to my lawyer, and that’s when they quit.”

Montgomery Police Department Headquarters is shown here on Oct. 1, 2024. Ivana Hrynkiw | AL.com

Authorities searched Melvin Roberts’ car, performed a blood test and seized his clothes, court records show. They didn’t find any evidence of the crime.

Detective Danny Carmichael, the primary investigator on the case back in 1992, described Melvin Roberts in his notes as “a very ignorant individual” and “very frightened of the police.”

Police notes from the time don’t indicate abuse of Melvin Roberts. But, he could recall those details even decades later. “I’ll never forget,” Melvin Roberts said in a 2022 deposition.

According to the judge’s latest order, Montgomery police “remained focused on Melvin (Roberts) until a Caucasian pubic hair was discovered on the trace sheet in which Mrs. Roberts’ body was wrapped.” The Roberts family was Black.

After that discovery, authorities pivoted and started to look for suspects who were white.

The new suspect

Police notes from the first days and weeks of the investigation were scanned into court records, memorializing the steps police took.

Dozens of reports from various officers and from Carmichael, the primary investigator, recounted interviews with scores of people — primarily teens and preteens who hung out in the Manley Drive area or who were affiliated with local gangs. Each of those interviewed pointed to another, creating a string of endless teenage tales in which police tried to distinguish fact from rumor. One boy interviewed, who gave cops over 10 names to look at, was in the eighth grade.

Carmichael wrote, after early interviews didn’t yield any results, “I directed that there would be no more overtime and I ceased work on this case at this time. This was on a Saturday afternoon and I did not return to this case until Tuesday morning.”

He made notes on all his interviews.

About the victim’s teenage son, he wrote: “I do believe he is an intelligent individual, but just sorry… the same dumb basic answers, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know.’”

And on the victim’s teenage daughter: “an even worse case to interview. She appears to be dumb, and slow… she was only frustrating (police) trying to interview her.”

But eventually, about a month after the slaying, some of those interviewed gave police the names of men sleeping behind the mall, casually mentioning that two men, both named Christopher — Christopher Barbour and Christopher Hester — may know something.

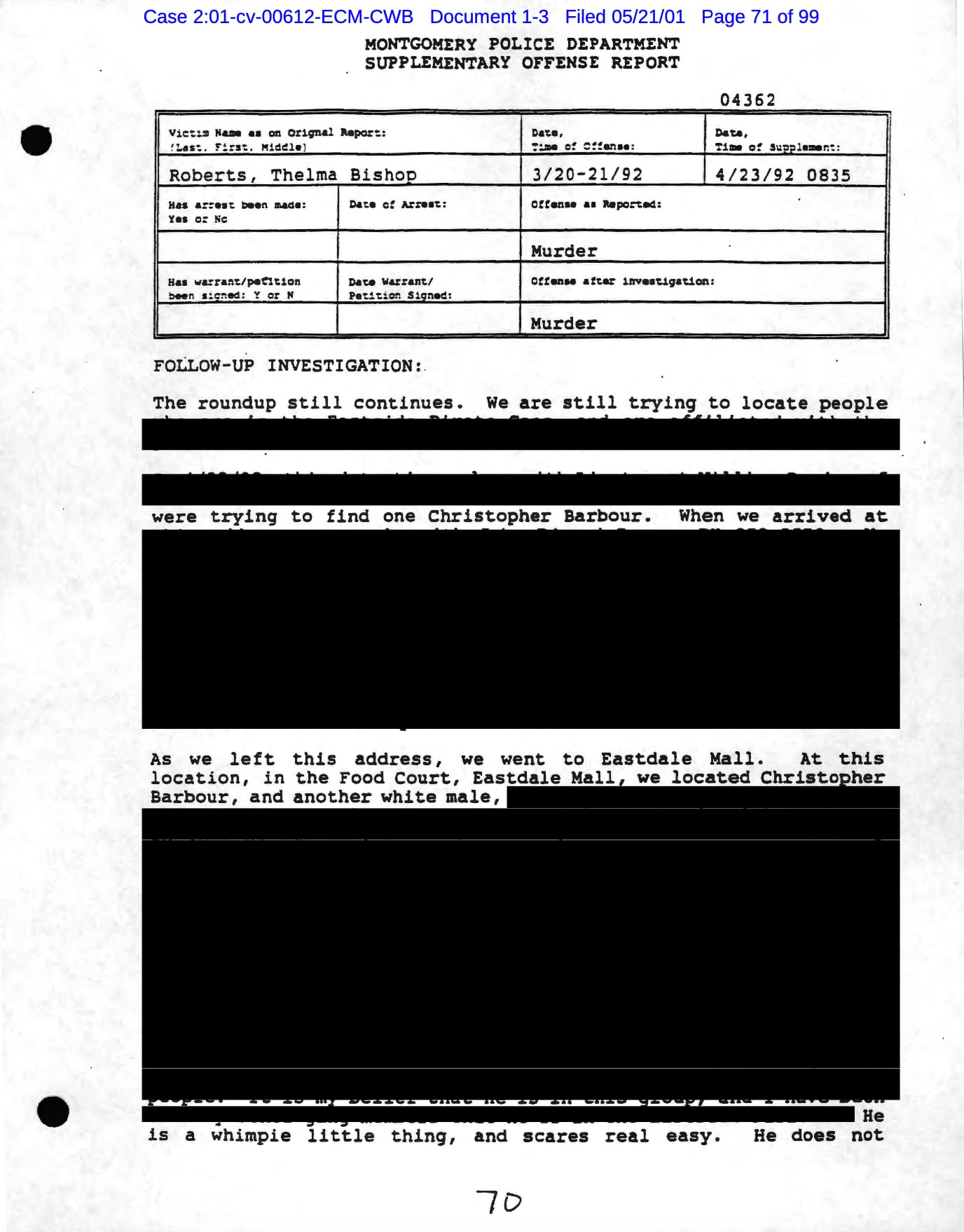

He and another investigator, former fire department Lt. William Davis, went to the mall and found 22-year-old Barbour in the food court.

They took him to police headquarters. “We questioned him intently,” Carmichael wrote.

“He is a whimpie little thing, and scares real easy.”

While Barbour didn’t appear violent, the cop wrote, he heard Barbour lost his temper when drunk.

“We did not get anything concrete from this individual… he denies emphatically.”

Barbour, wrote Carmichael in his notes, was “possibly a Satan worshipper” with “occult-type tattoos on his body.”

According to the prison system, Barbour’s tattoos, none visible on his face or neck, are of various skulls: a smiling skill, an iron cross with a skull, a skull in the clouds, and a flaming skull.

When Davis and Carmichael had previously visited the homeless encampment to look for Barbour, Davis noticed Winn-Dixie wrappers and packages. Davis told the court last year that he thought “Chris may be a viable suspect” for the grocery store fires.

A few days after the initial questioning, authorities again visited Barbour behind the mall.

Judge Emily Marks is overseeing Barbour’s lawsuit in the U.S. District Courthouse in Montgomery. Christopher Barbour has spent more than 30 years on Alabama Death Row for the slaying and rape of Thelma Roberts, but Marks says that new DNA evidence points to someone else. Ivana Hrynkiw | AL.com

The two spoke, and Davis said he wanted to talk with Barbour about the teenage group and the fires at Winn-Dixie.

On May 1, 1992, Barbour went to a nearby fire station and took a polygraph. He went because, Barbour said, “After being threatened with violence, you know, I wasn’t going to say no.”

But the polygraph didn’t focus on the grocery store fires, or the teenagers. It was about the slaying at Manley Drive.

“According to Barbour, the officers were verbally and physically abusive at times,” Judge Marks wrote in her August order, “and Detective Carmichael repeatedly slapped Barbour in the face when he did not know the answers to Detective Carmichael’s questions.”

At a hearing last year, Davis denied any misconduct involving Barbour and said he “had a very good relationship with Chris.” At one point, Davis told the court: “I can’t testify what Lieutenant Carmichael did. I was not present in any of that.”

He maintained there was no inappropriate contact with Barbour or other suspects in the case.

Attempts to reach Davis for this story weren’t successful. Carmichael has since died.

The confessions

A fire department lieutenant administered the polygraph, asking questions about the fires at the victim’s home. That lieutenant told officers that Barbour had failed the test. After that, police fed him dinner and Barbour agreed to talk.

Barbour wanted a tour of the fire station, so Davis showed him around. Barbour also got to sit on a fire truck.

“I go back over to my office, and I go through it again. I talk to him again about what happened… and then I took a taped statement,” Davis told the federal court last year.

According to the judge’s order, Barbour gave three confessions. None were in the presence of an attorney. Of the three, one was audiotaped and one was videotaped. One was not recorded at all.

After the polygraph, Barbour and the cops talked for hours before Barbour made a recorded confession, the judge’s order said.

“According to Barbour, he was shown crime scene photos and told details about the crime scene before he confessed. Barbour also claims that he ‘rehearsed’ his confession four to five times before Lt. Davis recorded it.”

Following the taped confession, Carmichael, from the police department, showed up. He took Barbour to the police station, where Carmichael and Barbour “talked for about three hours in an unrecorded conversation,” the judge wrote, before Barbour made a videotaped confession.

This is what Barbour told authorities happened on the night Roberts was killed, according to the federal judge’s order:

On the night of March 20, Barbour, Hester, and another man (who was a juvenile at the time and wasn’t ultimately prosecuted) were driving to Jackson’s house to hang out with his older brother. They didn’t know Jackson. When that man didn’t answer his door, Hester went to Roberts’ house, knocked on the door, and asked if the three men could drink inside. She agreed, and let them in. At some point, Roberts and Hester went to the bedroom. Barbour heard arguing, so he went to the back bedroom, and a physical altercation broke out. He then, along with the juvenile, held Roberts down while Hester raped her. Then, Barbour stabbed her and tried to set her on fire, before the trio left the house.

A police report, scanned into court records, shows Det. Danny Carmichael of Montgomery police’s initial thoughts after his first interview with Christopher Barbour. Barbour has spent more than thirty years on Alabama Death Row for the brutal slaying and rape of Thelma Roberts in 1992. Court records | AL.com

He didn’t mention the plastic bag left over her head, nor attempting to strangle her.

“Did that sound right to you?” a lawyer for Barbour asked Davis in court last year, according to transcripts. “Did that sound realistic to you?”

Davis replied, “I didn’t question it. I assumed that, and gathered that Mr. Hester knew Ms. Roberts. That’s the information that we drew.”

Davis also said he never gathered evidence that was consistent with Roberts letting three men into her home to drink alcohol. Later, autopsy reports showed no alcohol was found in Roberts system; no beer cans were found in the house, either.

In court in 2023, a lawyer asked Davis if the DNA match to Jackson made him doubt Barbour’s confession. He said no.

“Who Ms. Roberts may have had sex with prior to her being murdered is up to Ms. Roberts,” he said.

Davis said Barbour’s confession “nails all of the crime scene facts.”

The conviction

Barbour’s attorneys — both at his original trial and now — say the authorities threatened Barbour and slapped him in the face. Before his 1993 trial, Barbour’s first attorneys tried to get a judge to ban the confessions from coming into evidence. Barbour testified at that hearing, saying that typically only one officer was with him and would abuse him both verbally and physically.

Barbour told a judge after his arrest, “After that day, I had a bad fear that if I didn’t tell them what they wanted, or, you know… didn’t tell them something, that he was going to hit me more.”

Barbour’s lawyers said the police used “intimidation and aggressive tactics to coerce Mr. Barbour, including showing him photos of Mrs. Roberts’ body and the crime scene.”

Barbour said he was scared back when police talked to him in 1992 when he agreed to take the polygraph, and “described the alleged deception leading up to the administration of the polygraph test and its coercive effect on him,” the judge wrote.

“Barbour further testified that given the violence he had previously experienced from Detective Carmichael and the threats Lt. Davis had made to him, he ‘pretty much thought that [he] had no choice in the matter.’”

His grandfather testified in a 1992 hearing, too, before Barbour’s trial. He said Barbour was “very, very afraid” of the police after their first encounter, and how one of the investigators had “beat up on him.”

In 2001, while Barbour was on death row, he provided an affidavit. “I gave those statements only after I had become very frightened of both men and only after they had told me what I was suppose to say,” he said.

But three decades ago, Montgomery Circuit Judge William Gordon allowed the confessions to be used at trial.

When the case came before a jury in 1993, prosecutors told jurors how Roberts was beaten and stabbed, raped and burned. The prosecutor said, “semen was detected,” but didn’t say from whom.

They also told the jury about the hair found at the crime scene. No one could say how the hair got on the sheet wrapped around the body, but the hair was “dissimilar” to Barbour’s hair, according to the state’s forensic expert at trial.

Barbour was convicted and sentenced to death by a split jury vote of 10-2.

Several months later, the other Chris, Christopher Hester, pleaded guilty to a reduced charge, received a lighter sentence and ultimately served two decades in prison for the murder. But the story he told police was different than Barbour’s, and even implicated different people.

The juvenile Barbour mentioned wasn’t prosecuted.

Attempts to reach Hester were also unsuccessful.

The neighbor

Meanwhile, Jackson, who was 16 in March 1992, lived across the street from the Roberts family. According to court records, Jackson often told Roberts’ son that Jackson “was going to get his mama.” The teen thought his friend and neighbor was joking, he recalled in court, despite how Jackson repeated the phrase several times.

On the night of the murder, Jackson left the neighborhood house party, but returned later in the nighttime or early morning hours. Testimony from Roberts’ son said Jackson came back “kind of jittery,” asking the teen for a cigarette. Other teens at the party remembered that, too.

“All I know is when we went in there, Tyrone just was shaking, asking for a cigarette. And (Roberts’ son) was like, ‘it’s in my pants, it’s in my pants.’ He was like — I was like, ‘what’s wrong, why you shaking.’ He never would respond to me… he was like, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry.’ He just continued shaking, asking for a cigarette.”

Jackson was listed as one of several people who were in the front yard when police arrived after Roberts was found dead, and police notes show that cops tried to talk with him that afternoon, but he had already left for work.

Jackson left Montgomery soon after, moving to the Florence area in north Alabama, court records show.

In 2003, Jackson, then in his late 20s, was convicted of the murder of Monique Vaughn and sentenced to life in prison. Appellate court records in that case show that Jackson beat and stabbed Vaughn in her home in 2001, after she “rebuffed his sexual advances.”

Vaughn had let Jackson inside, as she was friends with his wife at the time. Autopsy reports show she suffered from multiple stab wounds and blunt force trauma to her head, and court records describe the crime scene inside as “massive,” with blood in almost every room in the house. Her baby was in his nursery during the attack, but was unharmed.

Jackson and Vaughn lived blocks away from each other in Florence.

The DNA

After years of legal battles, almost 30 years after the crime, Barbour’s legal team in 2021 was finally allowed to retest the semen found from Roberts’ 1992 rape kit.

The DNA testing came back to Jackson, The state confirmed the results, running a second round of testing by the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences.

Barbour’s lawyers found Jackson at Kilby Correctional Facility, outside of Montgomery. But he wasn’t keen to talk.

“It is puzzling that in this case, the State downplays the significance of the new DNA evidence when the State otherwise relies on similar DNA evidence to secure convictions and clear cold cases.”

U.S. District Judge Emily Marks

In a deposition, Jackson said officials from the Alabama Attorney General’s Office had already visited him. When the state prosecutors showed up and told him who they were, Jackson said he didn’t want to meet with them. He didn’t ask what it was about, only adding that he wanted an attorney.

Jackson, in the same deposition, didn’t say much to Barbour’s team, either. When asked if he knew Thelma Roberts or the Roberts family, Jackson said: “On the advice of counsel, I plead the Fifth.”

He repeated the answer about 50 times throughout his deposition to any questions that revolved around the Roberts family or the murder.

“I am through. I plead the Fifth to whatever else you got to say,” Jackson told Barbour’s lawyers at one point. “That is what I am going to say. So, we can go on and cut through the chase. Whatever your questions is, I plead the Fifth to the answers you are going to get. So, that’s — Get it over with.”

In September, Judge Marks reappointed a lawyer to represent Jackson, writing that he “remains a material witness who could potentially face a new threat of an additional loss of liberty.”

Christopher Barbour is pictured here inside of Holman prison. Provided Photo | AL.com

The state’s theory

The Alabama Attorney General’s Office doesn’t argue that the DNA, which the judge called “new, reliable evidence,” is inaccurate. But they don’t think it exonerates Barbour, either.

At a 2022 hearing, Assistant Attorney General Audrey Jordan argued that the semen only showed Roberts and Jackson had sex — not that Jackson killed her.

The state’s top prosecutors said Jackson and Roberts could have had sex prior to Barbour, Hester and the third man coming into the house and murdering her. They also argue that just because Jackson had sex with Roberts doesn’t mean Hester didn’t have sex with her, too.

“Although the DNA evidence places Jackson with Roberts at some point within twenty-four hours before her murder, there is no evidence regarding when, where, or under what circumstances the sexual contact occurred between them,” lawyers for the state wrote in a filing last year.

“It does not disprove that Barbour was present when Thelma Roberts was murdered, and it does not disprove that codefendant Hester raped Thelma Roberts, as Barbour described in his confession, without ejaculating.”

The judge seemed to disagree. In her order, Marks wrote that the Alabama Attorney General’s Office “downplays the significance of the new DNA evidence.”

“And the other evidence inculpating Jackson, including his actions and statements around the time of Mrs. Roberts’ murder and before, his other criminal history, and his Fifth Amendment invocations in this case, further bolsters the significance of Jackson’s DNA alone being found inside Mrs. Roberts because it is additional evidence that someone else — Jackson — may have committed the crimes of which Barbour was convicted.”

The judge weighs in

Despite the DNA evidence, Barbour remains on death row. And the case is far from over.

Lawyers for both sides will meet with the judge on Oct. 9 for a status conference to determine filing deadlines for what comes next. But the judge has already made clear she has problems with the state’s theory.

In her order, Marks wrote that Barbour has several pieces of evidence on his side, and “the centerpiece is the DNA test results establishing that the only male DNA removed from Mrs. Roberts’ body belonged to Tyrone Jackson.”

She wrote that a DNA match to Jackson would make a jury believe that Jackson was at the crime scene and involved. But Barbour never mentioned Jackson, calling his whole confession into doubt. It would, at least, “more likely than not cause reasonable jurors to have reasonable doubt about the reliability of Barbour’s confessions, and thus his guilt, and to link a new third party to the crime.”

But the judge went further, casting doubt on the state’s theory that might explain the DNA, that maybe Roberts had sex with a neighborhood boy shortly before she was attacked by a group of homeless men.

“As a threshold matter, any reasonable jury would doubt the veracity of the claim that Mrs. Roberts, a forty-year-old churchgoing woman, had consensual sex with Jackson, her sixteen-year-old neighbor who was a year younger than her own son…. Reasonable jurors also likely would not accept the State’s consensual sex theory given the physical evidence, DNA test results, and expert testimony.”

“Additionally, for the State’s consensual sex theory to be true and consistent with the prosecution’s theory at trial, it must also be true that detectable amounts of Jackson’s semen remained inside Mrs. Roberts even after Hester raped her, and that Hester left no DNA behind.”

“That is a bridge too far. Applying Occam’s Razor, the physical evidence, DNA test results, expert testimony, and common sense would cause reasonable jurors to doubt the veracity of the State’s theory that Hester raped Mrs. Roberts after she had consensual sex with Jackson when only Jackson’s DNA was present.”

The judge also questioned why the state didn’t lean more heavily on DNA in this case.

…unlike people, ‘DNA doesn’t lie.’”

Judge Emily Marks

“DNA evidence is sufficient for many juries to convict beyond a reasonable doubt. By the same token, it is also sufficient to create reasonable doubt,” she wrote.

“It is puzzling that in this case, the State downplays the significance of the new DNA evidence when the State otherwise relies on similar DNA evidence to secure convictions and clear cold cases.”

Marks wrote that if a jury had all of the evidence in the case, it would be “unlikely to accept” that Jackson and Roberts had sex prior to being raped and murdered by another group of men “because the theory defies logic, common sense, and science.”