Here’s how parents can fight book bans in their kids’ school libraries

Kathryn Hammond has applied for a spot on the literacy committee in the central Florida school district where her son attends school.

It’s one of the largest school districts in the nation and it’s where she taught middle school English for more than a decade. The literacy committee reviews books and other materials that are challenged by parents over their content to determine whether they should be removed from school libraries.

Hammond worries what will happen to the diversity of books at her son’s school if parents like her do nothing.

“I have the right for my son to have access to those reading materials. Nobody gets to speak for our family,” Hammond said. “And the rules in my house shouldn’t extend to the homes of other people.”

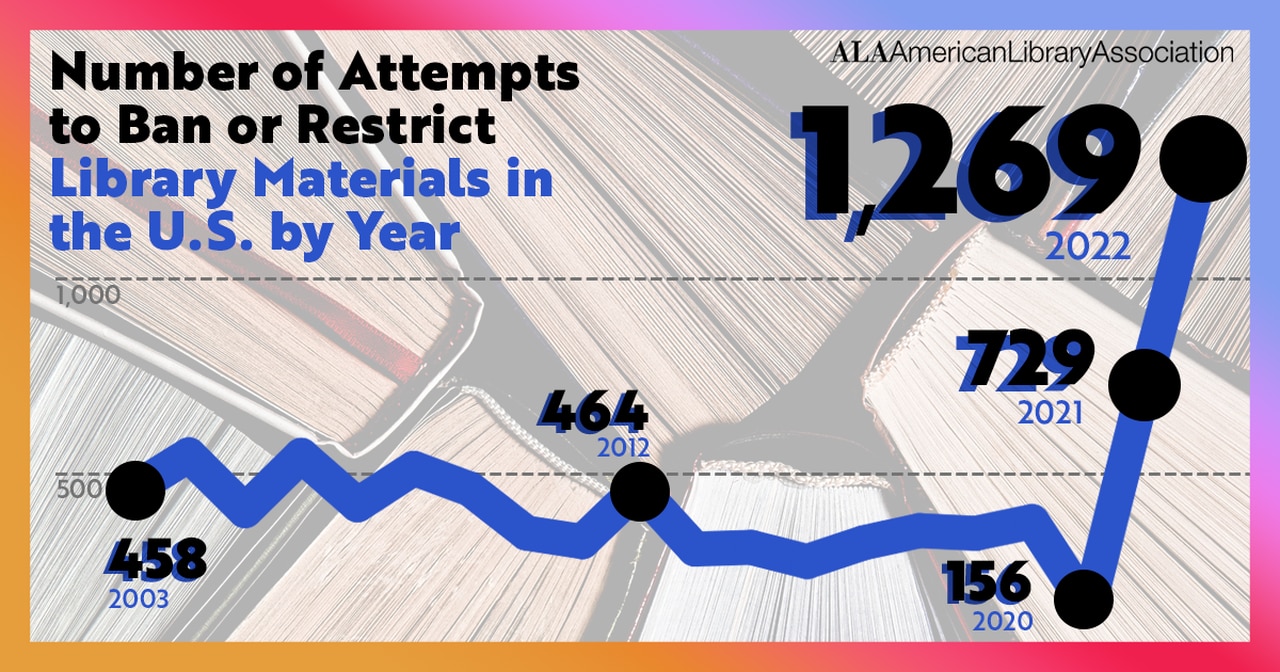

The number of book challenges has soared in recent years, nearly doubling between 2021 and 2022, according to the American Library Association, a nonprofit trade organization that tracks book censorship.

Last year was a high-water mark, with the highest number of attempted book bans since the ALA began tracking them 20 years ago. More than half of the 1,200+ challenges last year specifically targeted school and classroom libraries.

“Most of the books being challenged are books about marginalized communities or written by people from those marginalized communities,” said Kathy Lester, a Michigan school librarian and the president of the American Association of School Librarians. In 2022, most of the books targeted for censorship were written by or about people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

In 2022, attempts to ban or restrict library materials in the United States reached an all-time high, according to the American Library Association, which tracks book bans and advocates against censorship.

Book battles have been waged by parents in school districts from Louisiana to Texas, Michigan to Hammond’s home state of Florida.

“I want to be a voice for students who deserve to have the opportunity to go into a library and find a book where they see themselves represented,” Hammond told Reckon. “Representation is incredibly important, whether it’s a book about LGBTQ characters or robotics or art.”

Who’s behind the surge in book bans?

Organized conservative parent groups are among the biggest drivers behind the recent surge in attempted book bans, according to organizations like the ALA and free speech organization PEN America. Nearly all of the books challenged in 2022 were part of cases involving multiple books challenged at one time, according to the ALA. Many of those cases involved 100 or more books at one time.

Groups involved in book challenges, like the Moms for Liberty or Utah Parents United, are often well-coordinated, they maintain connections with local and state conservative politicians and, in some cases, are funded by national political organizations.

Group members share lists of targeted books on social media and show up at school board meetings in their own districts to demand the books’ removal.

Hammond has seen it in her own school district, where parents and even school board members echo talking points of politicians, complaining that certain books promote the “indoctrination,” “grooming” or “sexualization” of children.

“It seems like there’s this very made-up culture war and no matter what lens you look at, the teacher is to blame,” said Hammond, who said she left teaching in part because of a lack of support for teachers and an increase in hateful rhetoric aimed at them.

She said she’s watched in recent years as the conversation around parental involvement in school switched from volunteering for the PTA to, “‘hey parents, don’t be dumb, you have to get involved because all these terrible things are happening at school.’”

Most of these groups are relatively new. Nearly three-fourths of the 300+ book ban groups tracked by freedom of speech nonprofit PEN America appear to have formed since 2021. Many use common language and tactics, describing books by or about LGBTQ or Black people as inappropriate or pornographic.

“Their aim is to suppress the voices of those traditionally excluded from our nation’s conversations, such as people in the LGBTQIA+ community or people of color,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, in a statement.

What do most parents want?

The parents calling for book bans in schools may be loud, but surveys suggest they’re in the minority.

“Surveys show that more than 70 percent of Americans are against book banning,” said Lester. “They want access to information, they want freedom to read and they want that for their children as well, at age-relevant levels. Those parents need to also speak up.”

Parents who want books inclusive of race and gender in their children’s school libraries have to be willing to speak up, said Hammond, even if they lack the organization and funding of the groups calling for bans.

And it works. In Michigan last year, Lester said, pro-censorship groups attended the state board of education meetings and dominated the public comment time with their concerns about “pornographic” books in school libraries. Eventually, groups of parents who opposed book bans began attending the board meetings, speaking up, and countering the narrative that all parents wanted those books removed, she said.

“Students having free choice in selecting reading materials that speak to them or are meaningful helps reading achievement,” said Lester. “Students will tell you they felt less alone or felt more seen after reading a book and realizing there are other people who feel the same as they do or have similar experiences.

“And I also believe if we can read about people who are different from us, it builds empathy. That’s something I feel our society could really use right now.”

April is National School LIbrary Month. Below are suggestions from experts for parents who want to advocate for keeping books in their kids’ schools.

If books are being challenged in your school, what are your options?

1. Speak up & show up.

Book challenges are typically made and decided at the local level, so attend your local school board meeting. Most meetings include time for public comments. Sign up to speak and let your school district leaders know how you feel. Ask if the district’s policies on book challenges and removals are being followed. If you have the time, get a group of parents together and attend state board of education meetings as well.

“It made a big difference at our state level when more and more people were showing up in support of the freedom to read and students’ rights,” Lester said.

If you don’t have the time to attend a local or state school board meeting, you can always look up the contact information for your school board representative and school district superintendent, then call or email them.

2. Invite your kids to join you.

“I think it’s always powerful when school boards hear from students as well as parents,” said Lester. If your students are comfortable speaking and feel strongly about a potential book ban, she said, bring them with you to the school board meeting – or have them write their own email to school district leaders.

3. Join the committee.

Most school districts have a policy for how books are purchased and approved for school libraries. Many also have a review process for how a book can be challenged and what criteria must be met before it’s removed from a school library.

Contact your school district and ask if there’s a literacy review committee you can apply to join, Hammond said, or another way to get involved in the book selection and review process. If there is no process, you can ask district leaders to develop one.

4. Get the word out.

Sometimes it takes a larger public outcry for school officials to act. Parents and students can contact their local media outlets, Hammond said, to share their stories and concerns.

Posting on social media about your concerns can also be a good way to find other like-minded school parents.

5. Join a larger group.

National groups are working on intellectual freedom issues, including school book bans, and can provide resources for parents. Unite Against Book Bans, an initiative of the ALA, offers an online toolkit with research, tips and talking points to help parents get started.

Since many of the battles over school library books are fought at the local level, search social media for smaller groups such as those focused on BIPOC or LGBTQ+ books, or groups based in your geographic area like the Florida Freedom to Read Project, Freedom to Read Georgia or the FReadom Fighters in Texas.

Know a group working to combat book bans in school libraries? Tweet at @reckonnews or email [email protected] to share and we’ll add them here.