He waved at a white woman in Alabama in 1957, witness now says. His murder remains unsolved

It was a mild afternoon in late October 1957 when 17-year-old Carolyn Haigler went for a ride with her friend through the quiet roads of rural Lowndes County, Ala, just to the west of Montgomery.

That’s what bored teenagers did for entertainment in those days, she recently said, white teens anyway. Bereft of entertainment today, Lowndes County was even more absent of fun distractions in the 1950s. So, on that pretty fall day, she jumped in the passenger seat to cruise the blacktops of this part of Alabama’s Black Belt. She and her friend aimed to ramble along State Route 97 and to the roads beyond, just as she had done many times before with her 16-year-old classmate from Hayneville High.

It was as bland a drive as ever, through the bucolic landscape, into the pine forests and past the pastures. They bounced along, soaking in the uneventfulness of it all, until the car approached a young Black man paused on the roadside, not far, she recalled, from the turnoff to a dirt lane everyone called McCurdy Road.

As they got closer, this figure began waving, gesturing to the girls.

That moment 67 years ago comes back to Haigler, now Carolyn Ikenberry, pretty easily these days. Afterall, she has been sitting with it for decades now, ruminating over the tragedy and injustice that followed.

“He wasn’t in distress,” said the 84-year-old Ikenberry, in a call from her home in Chapel Hill, N.C. “It was more like… he was trying to flag us down, asking for a ride.”

Ikenberry explained that the young man’s actions were non-threatening. And even if they had been in some way menacing, she said, the young man certainly did not pose any danger to the girls as they were barreling down the two-lane blacktop outside Hayneville, the county seat, in excess of 40-miles per-hour.

“I didn’t think anything about it,” recalled Ikenberry in a recent call. But her friend, she said, “became visibly upset and said, ‘I’m going to tell my father.’”

The person on the side of the road waving at them that day, she said, was almost certainly 18-year-old Rogers Hamilton. He was the son of a sharecropper who lived with his mother and a collection of about a dozen siblings and cousins in a small house just off Alabama 97 and up McCurdy Road. He was the oldest of the children in the household and the family breadwinner, a regular worker for the landlord, the McCurdy family. The McCurdys knew him well, according to Ikenberry and others, and would often stop to give him and other members of the Hamilton family a ride.

But her friend did not know Hamilton and grew agitated. A black man making even the most harmless gesture in the direction of a young white woman in parts of the rural South in the 1950s could lead to violence. It was only a couple of years earlier, when 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered by white men in Money, Miss. after being accused of offending a white woman.

“I remember how upset she was and I tried to calm her down. I specifically asked her not to tell her father,” recalled Ikenberry recently.

Late that night, Rogers Hamilton lay dead, shot in the head, not far away on McCurdy Road.

The next day, Ikenberry says, she found out about the killing and became upset, even hysterical, about it. “I don’t know what I thought would happen,” Ikenberry said of the young man on the road and her friend’s reaction to it. “But I know I never thought he’d be killed.”

The Rogers Hamilton murder has long been known to federal and state law enforcement authorities and to history. He has been the subject of reporting and is on a list of victims of suspected racially-motivated murders between the early 1950s and late 1960s, published by the Southern Poverty Law Center in the early 2000s. The U.S. Department of Justice has also examined the case since the publication of that list in the early 2000s.

A report from the Alabama Bureau of Investigation, contained in an FBI file, spelled out most of the details of what happened on Oct. 22, 1957: the young man was taken from his home after midnight and driven up the road a bit where one man shot him in the head.

Details, especially names of suspects, are absent in the reports from the time. Family members, however, have often pinned blame for Rogers’ death on a well-known, violent and drunk-prone deputy sheriff named Luck Jackson (or Lux, as the family spells it) who died in the early 1980s.

That’s been previously reported. But what’s never been established is why he was murdered. No one until now has publicly shared the specifics of the story of the wave toward a passing car or the name of the young woman driving that car.

Also, Hamilton’s family members have long insisted there were two men in the truck that night. Even if one were Deputy Jackson, as the family has maintained, then a mystery has surrounded who the other may have been.

Now Ikenberry’s story, decades later, may provide a clue to that other person’s identity.

She has a clear memory of that day and has offered up plenty of details in the past few years to anyone who would listen. But until now, publicly, she hasn’t come forward with the name of her young friend who was driving the car that day.

“I don’t know what I thought would happen. But I know I never thought he’d be killed.”

Carolyn Ikenberry

She had been reluctant, she said, to offer her friend’s name to documentary filmmakers who came calling back in 2022, or to a journalist who pressed her for that name in late 2024, because she thought the person driving that day should come forward herself. All that, however, changed when her friend died.

Her friend’s name, Ikenberry said, was Hulda Coleman. On a recent phone call, Ikenberry said Coleman was the one who was upset by the wave.

For any student of the blood-letting incidents of the Civil Rights Movement, that last name may ring loud. Hulda was the daughter of Tom Coleman, an agent of violence and oppression in Alabama’s Black Belt in the 1950s and 60s.

Much like Lux Jackson, Coleman had a reputation, Ikenberry and others said. Everyone knew how he felt about black people, Ikenberry said. (He did not like them.) “Everyone knew what a hot head he was.”

It was Coleman who in August of 1965, drew his shotgun and killed a 26-year-old Episcopal seminarian named Jonathan Daniels and injured his colleague, the former Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe outside a store in Hayneville. In court, he claimed self defense. He was acquitted in September of that year by an all-white jury.

That Ikenberry’s story of that long-ago car ride has been made public can’t change anything in the Hamilton case, given the fact that practically everyone who could have been involved in the young man’s murder is dead. Tom Coleman died in 1997.

Still, it’s a story Ikenberry has long wanted to tell and something Hamilton’s family wanted to hear.

The basic facts of the case were long ago laid out in a report by Oscar Coley, the ABI detective, who visited Lowndes County the day after the murder. Coley, who drove up from the Mobile office, interviewed members of the family, including Rogers’ mother, Beatrice Hamilton, the landlord George McCurdy and others.

Beatrice Hamilton gave a detailed account to Coley of what she witnessed that night. She told him she heard a truck drive into the yard, that a man called Rogers’ name. She woke her son to go outside, thinking it was the landlord needing him for some chore. After sending him outside, she realized it was not McCurdy, but someone else. By the time she went into the yard to intervene, Rogers was in the cab and the truck was headed down the lane, back toward Highway 97. She followed on foot and up the trail, she said. That’s when she saw the truck had stopped. Rogers was standing there, with a man. This man reached into his pocket, she told the detective, pulled out a gun and shot her son in the head. Then the truck drove away.

She didn’t identify the man as the deputy to Coley. But family members have long said that Beatrice Hamilton maintained that Lux Jackson shot her son.

Back then, she also told McCurdy, her landlord, that two men were in the truck. That was supported by Rogers’ 14-year-old sister, who was in the house that night. But the family never identified the second man.

The investigation went nowhere. That’s despite details offered by Beatrice, such as the color of the truck and the color of the man who fired the shot. Also, according to an investigative file dated December 1957, FBI agents knew about rumors circulating, including one passed to them in November of 1957 by Sheriff Frank Ryals that Rogers “had been killed by a white man as a result of having waved at a white woman passing in a car.”

Signs of Remembrance

These days Carolyn Ikenberry engages in racial-justice efforts whenever she can. It’s what she does in her retirement, that and disaster relief. She prints the name ROGERS HAMILTON on the poster boards she carries to protests around North Carolina.

“The poster I’ve carried to the marches simply says ‘Rogers Hamilton Lowndes Co, Alabama, killed in 1957.’”

It’s been her way of honoring young Rogers and reminding the world of his death so many years ago.

Why, then, the question begs, has she waited so long to tell this rest of the story publicly?

“I have told this story to many people over the years,” Ikenberry wrote in an email.

Until a few years ago she didn’t know his name. But on a visit to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, she said, “I saw something written about his death that made me know it was the same young man who waved to us. I didn’t go to the authorities because I didn’t have any identifying information and in Alabama, until recently, nothing would have been done to follow up.”

She basically had no confidence law enforcement would do anything.

She started to tell this story publicly back in 2022 for the documentary Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power. Early in the film, she begins telling the story of that ride in the countryside, but doesn’t mention names, including Hamilton. Two years later, she explains that she felt like she was being asked to establish a scene-setter, to be an explainer of the oppressive environment for African-Americans during that period.

Recently Ikenberry called Beatrice Christian, Rogers’ younger sister. She was 14 at the time and was at the family home on the night Rogers was killed.

She’s now 81. When a reporter reached her at her home in Cleveland, Christian said she appreciated Ikenberry’s call and the work of others in adding new details to the public record. The new information about Tom Coleman’s daughter, she said, was important but, “this just doesn’t change anything, does it?”

Her brother, she said, is still gone and no one has ever been made to pay for his murder.

She repeated what she said in an interview in 2010, saying that a pickup carrying at least two men came to the house in the middle of the night. The men called to Rogers and he went outside. After a brief conversation, they put him in the truck, drove up the road and shot him.

She added, however, that the story Ikenberry tells seems plausible. All of her family had a good relationship with the McCurdys. They were nice people, she added, and it stood to reason that her brother might have mistaken Coleman’s car for one owned by someone in the McCurdy family when he waved.

“Betty McCurdy was a really nice person,” she said. “George McCurdy’s mother used to take me out to the farm and get me to open the gates for her. She was a nice lady too. I didn’t want to open those gates but she was nice about it.”

Ikenberry’s memory of the events of Oct. 21,1957 are bolstered by 85-year-old Betty Wible Lewis, a long-time friend of Ikenberry’s who now spends most of her time in Lowndes County, having lived outside the South for years. Lewis explains that in October of 1957 she was a freshman at Auburn and had come home briefly to visit. She was at a store called Holiday’s, she said, in downtown Hayneville.

“As I was coming out of Holiday’s, Hulda Coleman pulled up in her car,” said Lewis, in a recent phone interview. “I could tell she was so upset about something.’

The two knew each other, Hayneville being such a small town and having attended high school together. Coleman proceeded to tell Lewis that she had encountered a young black man on the side of the road, waving at her.

“I tried to calm her down,” said Lewis, but she wasn’t having any of it. “I said, ‘He couldn’t have hurt you.’ She was so upset, and I told her she didn’t need to tell anyone about this.”

Lewis said she was visiting her mother, an employee of Alabama’s Office of Pensions and Security, at the courthouse that day. She later told her mother about the encounter with Hulda and how upset the 16-year-old had been.

Betty’s mother Olive happened to be a friend and work colleague of Betty McCurdy, whose husband George owned the land Hamilton and his family lived on.

The next morning, October 22, 1957, Olive informed her daughter that Betty McCurdy had told her about Rogers’ murder.

“I felt terrible, and somehow guilty when I learned that Rogers had been shot,” Lewis said in a recent phone call. “If I had paid attention to Hulda and just sat down with her and tried to talk her down, I might have been able to prevent what occurred. Instead, I treated her as the somewhat silly and not very bright girl that I already thought she was. I failed Rogers and his family as did so many others in Hayneville.”

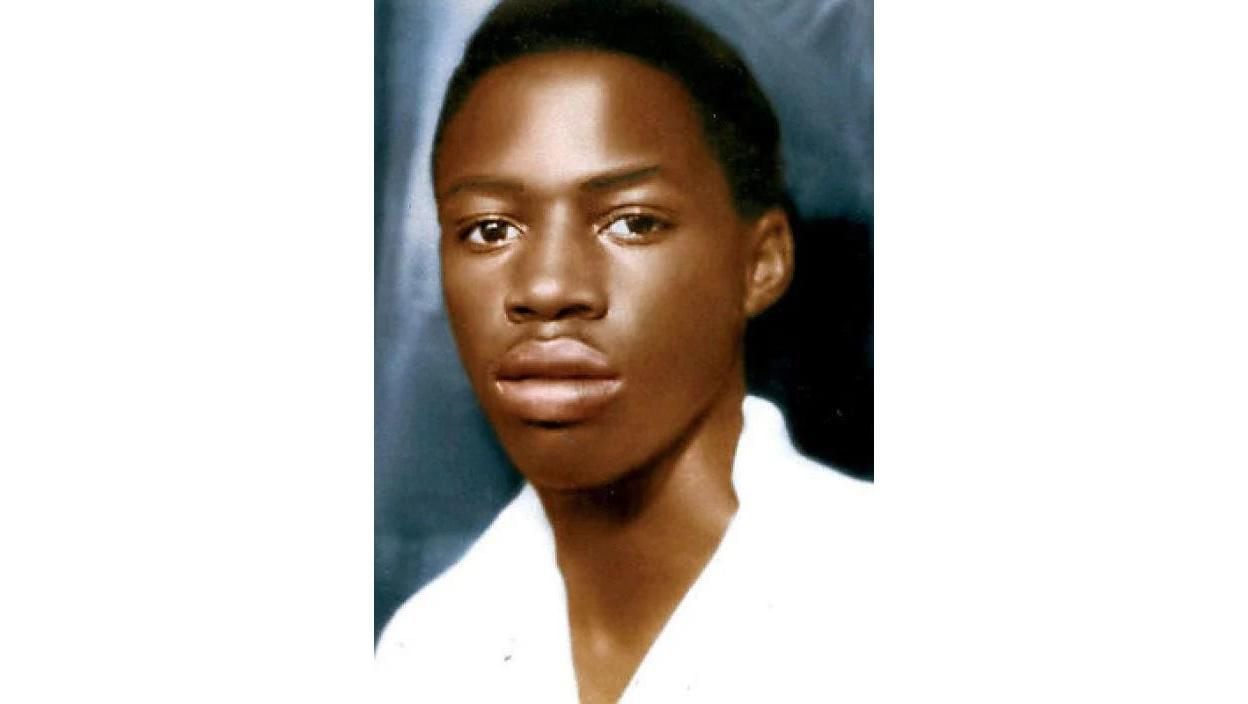

Rogers Hamilton was shot and killed on Oct. 22, 1957 in rural Lowndes County, Ala. when he was 18 years old. Contributed photo

Lewis said that her mother told her Betty McCurdy was upset about what had happened. She said the wave could have been intended for the McCurdy’s, as they drove a similar car to Coleman.

“She thought Rogers probably tried to flag the car down thinking it was Betty McCurdy’s,” said Lewis.

As for Carolyn Ikenberry, the day to tell this story publicly has been a long time coming.

When she went off to college, she said, “I left Hayneville in the rear view mirror. It was hard to leave my family, but it was good to get away.”

All these years of holding that story, she explains, has weighed on her. Searching for a way to explain it, she reaches for The Hound of Heaven, a late 19th-Century poem by Francis Thompson. Throughout the poem, the narrator speaks of a gloom cast over his life, a kind of shadow he tries to escape.

It is like in the poem, she wrote, “this experience has followed me all my life, sometimes in the background and sometimes in the foreground…. but it has been nagging at me since it happened, prodding me to find a way to let it be known what happened.”

Rogers’ older sister, Elizabeth Bell, now 87, was living in Chicago when Rogers was murdered. She is still there today.

Shortly into a recent call with a reporter, she interrupted to say that the events of October 1957 are never far away for her.

“I think about my brother every single day,” said Bell. “That took a toll on me, it took a toll on all of us, all those years without him.”

The last time she saw her brother was a few months before he was murdered, on a short visit to see the family. She said he told her of his plans to marry soon and she had a laugh with him about being a farm-boy groom.

“I was joking with him, of course,” she said. “After my brother told me he was planning on getting married. I said, ‘How you going to get someone to marry you? You working on a farm and you driving a tractor and all that?’”

“I think about my brother every single day. That took a toll on me, it took a toll on all of us, all those years without him.”

Elizabeth Bell

Rogers, she said, was her younger brother but in a way he was the father of the family. He worked for McCurdy and did more than his part in taking care of the family.

“In fact,” she said, “he’s the reason I am in Chicago.” It was Rogers, she said, who lent her and her husband $13, which helped them to buy bus tickets to move there to find work in the 1950s.

She takes a moment that stretches into a longer silence, before repeating, “I think about my brother every day.”