Harry Belafonte supported MLK’s family for many years: ‘It was my task to … take care of Coretta’

On April 5, 1968, the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Xernona Clayton rushed out of a downtown Atlanta dress shop with a handful of dresses and no idea of how to pay for them.

Coretta Scott King had a million things on her mind. Clayton, a trusted family friend, wanted to make sure King’s widow looked good in what would be days of public mourning.

When she arrived at the Kings’ Sunset Avenue home, a tall man greeted her at the door. He was curious about the bundle of clothes.

Clayton told him that she had gotten them from the store with the promise that she would return as soon as she could come up with the money to buy them.

Harry Belafonte reached into his back pocket and pulled out his credit card.

“Don’t you worry about it,” he told Clayton. “Get her whatever she needs.”

“She looked nice every day,” Clayton said. “That was Harry Belafonte’s concern for small details. We were interested in her wardrobe because she had so much thrown at her all at once.”

On the surface, Belafonte was a famous Black actor and singer, best known for his “The Banana Boat Song” and movies like “Carmen Jones.” He was able to cross over into mainstream culture in the 1950s and 1960s — in the class of Sidney Poitier and Dorothy Dandridge — in part because of his good looks and smooth voice.

But people who knew him paint him not as a celebrity, but as a man deeply committed to human and civil rights.

“Harry helped create the movement,” said former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young. “He was an essential star in the movement. He was not just an entertainer supporting the movement. He was legitimate.”

Belafonte died Tuesday in his Manhattan home at the age of 96.

But his ties to Atlanta, and Martin Luther King Jr.’s family, ran deep.

After meeting King in the 1950s, Belafonte became a major financial supporter of the civil rights movement and Atlanta’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In 1958, King was nearly killed in Harlem by a woman named Izola Curry, who stabbed him in a story that he would eerily recount in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech the night before he died.

Belafonte recalled that the stabbing shook King, who worried about the welfare of his family.

“I said to myself, our leader cannot be concerned about that. That burden should not be on his shoulders,” Belafonte told Democracy Now! in 2006. “We brought resources, and it was my task to direct all that, watching the kids grow, put money aside for their studies, to take care of Coretta, to make sure she had every convenience at her disposal.”

He enlisted his Hollywood friends like Poitier, Josephine Baker, Sammy Davis Jr., Paul Newman and Marlon Brando to offer support through donations, appearances or concerts. Belafonte would spend parts of his personal fortune to bail King and other activists out of jail, pay hospital bills, buy food or keep the lights on another month.

“Dr. King knew he could count on Harry,” Clayton said. “It was easy to run out of money and Harry was the one person who was always ready to do what he could to make up the deficit.”

Clayton, who went on to become a media trailblazer worthy of a statue in downtown Atlanta, remembers sitting with Belafonte and Coretta Scott King over King’s body at Spelman College’s Sisters Chapel in Atlanta.

Coretta wanted the waiting crowd to come in, but Clayton insisted they wait because King “looked awful.”

After arguing with the mortician, who said he had done all he could, Clayton asked Julie Robinson, Belafonte’s wife, to give her some face powder foundation. She also got some from King’s mother.

She mixed it up to match King’s complexion.

Belafonte quietly and carefully removed a handkerchief from his own coat pocket and placed it around King’s neck before Clayton applied the makeup.

“We didn’t see Harry as a great singer, as much as a great humanitarian,” Clayton said.

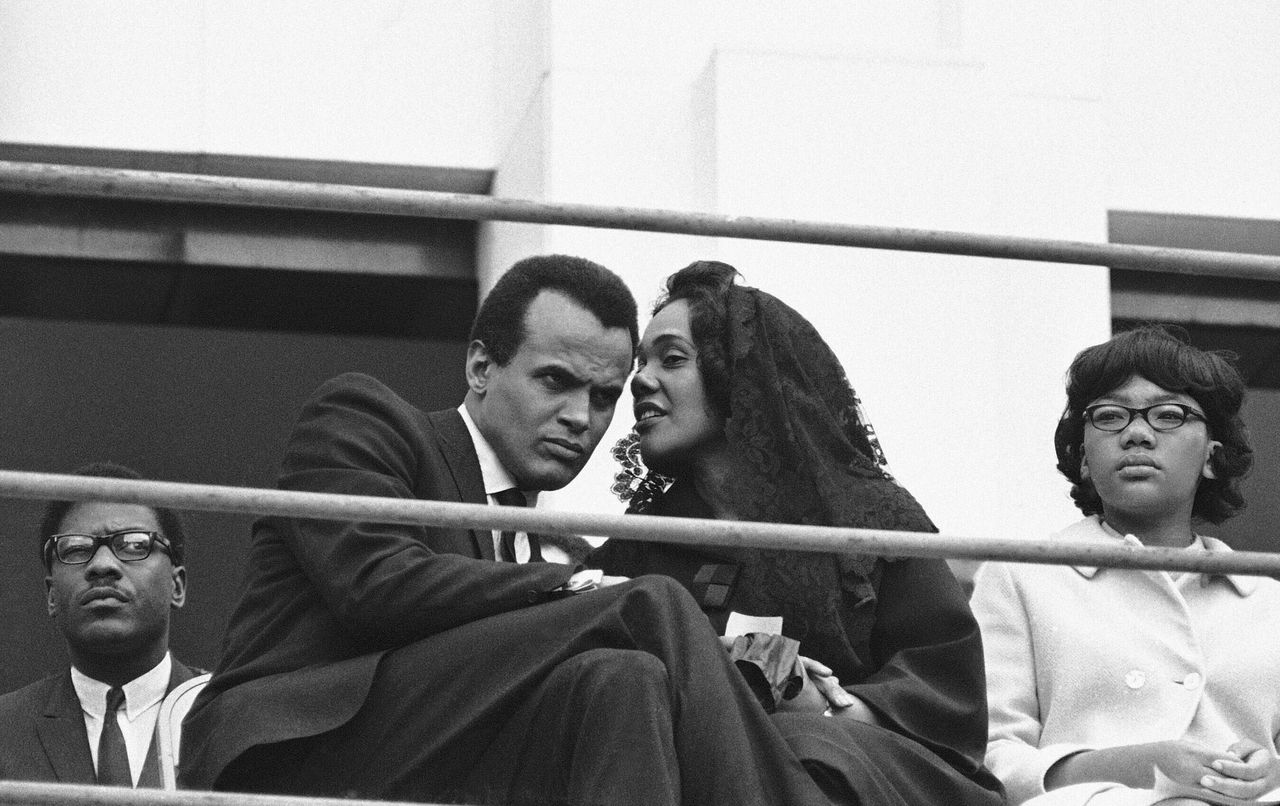

In the week following King’s death, Belafonte was a constant presence at Coretta Scott King’s side. On April 8, he went with her to Memphis to lead the march that King had planned. At the April 9 burial at South-View Cemetery in Atlanta, Belafonte, his face swollen with tears, sat beside a black-veiled Coretta with his fist inside his mouth to hold back his sobbing.

Belafonte would go on to provide financial assistance to the King family for years after King’s death.

In a tweet after Belafonte’s passing, Bernice King, King’s youngest child, reflected on the close relationship Belafonte and her father enjoyed. She posted a photo of a weeping Belafonte alongside her mother, Coretta Scott King, at her father’s 1968 funeral.

“As a child, I remember Harry Belafonte as a very compassionate man who loved my family,” Bernice King said Tuesday, noting that Belafonte was on the King Center’s first board of directors. “He often paid for my and my siblings’ babysitter while my mother and father worked on various civil rights campaigns.”

But in the moments immediately after Coretta Scott King’s 2006 death, the relationship between Belafonte and the King children became strained.

Belafonte had originally been scheduled to deliver a eulogy at Coretta Scott King’s lavish funeral. On the day before the funeral and two days after then-president George W. Bush had agreed to attend the services, Belafonte received a series of calls informing him that he would not be allowed to speak.

It is unclear who gave the order but Belafonte had been a harsh critic of Bush, one of four presidents who spoke at the funeral. (Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton also spoke; a young Barack Obama was in the audience.)

Belafonte had criticized the U.S. invasion of Iraq and just months before the funeral had called Bush “the greatest terrorist in the world.”

“When the final call came (from a King family member), it was — they were sorry, but the invitation — the withdrawing of the invitation would stand and that if I came down, they would find a place for me in the church, but I would not speak,” Belafonte said in 2006. “I did not go at all. I did not know how to deal with that.”

Clayton would not comment on the incident, but Young called the situation “a mess,” and said that Belafonte was devastated.

“It should have hurt him,” Young said. “He was the only one that took care of Coretta and made sure that the family had money.”

In 2013, Belafonte sued King’s three surviving children over the ownership rights of three King documents that he said were his property but that the children said belonged to their father’s estate. Belafonte had planned to sell the items, including notes for King’s last, undelivered speech, recovered from his suit pocket after his assassination.

The lawsuit was settled the next year, with Belafonte retaining possession and withdrawing the items for sale.

“Though there were moments of disagreement, I realize and appreciate the love and concern that he had for my family,” Bernice King, the CEO of the King Center, said in a statement to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “I am especially touched by the way he inspired a new generation of entertainers to become engaged in social justice causes. Today, I can unequivocally say that the world is a better place because God blessed us with Harry Belafonte.”

Sometime around 1969 or 1970, Young visited Belafonte in New York City. Young needed his help to keep the SCLC, which was floundering without King, afloat.

“He wasn’t interested. He said he was interested in trying to get people into Congress,” Young said.

The conversation was jarring, Young said, adding that it took him back to a discussion just days before King had been killed. Belafonte had gathered King, Young and a host of young preachers and wannabe politicians in a Manhattan hotel room to talk about ways to carry the movement forward — beyond boycotts and mass demonstrations.

“Belafonte said you shouldn’t have to have 1,000 people marching. You should be able to pick up the phone and call your congressman, mayor or city councilman to share your views and concerns,” Young said of that earlier meeting.

On this day, the two of them spent the afternoon throwing out names of potential candidates. Then a frustrated Belafonte bolted out of his seat and picked up the phone to call his wife.

He told her to get in touch with Poitier, Lena Horne and anybody else who had money, because “Andy is running for Congress.”

A stunned Young sat and listened to the call. He ran and lost in 1970. But in 1972, he was elected the South’s first Black congressman since Reconstruction.

Young said it had been a while since he had talked to Belafonte, who had been sick for some time.

“He sang, ‘Daylight come and me wanna go home,’’’ Young said. “He was ready to go home. I don’t feel sad, I celebrate his life. He was a true brother.”

©2023 The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Visit at ajc.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.