Goodman: For Alabama and the SEC, tough questions 50 years in the making

This is an opinion column.

_____________________

There was an awkward moment on Monday during a luncheon in Birmingham that centered around the topic of race and sports.

Imagine that.

It was nothing bad. In fact, it was a positive and necessary step along that long, winding, sometimes bleak, other times hopeful path of progress. Talking about the tough stuff, and putting everything out there, is how the healing happens. This is what my therapist tells me. When it involves beef tips, winter greens and strawberry cake, well, that’s even better.

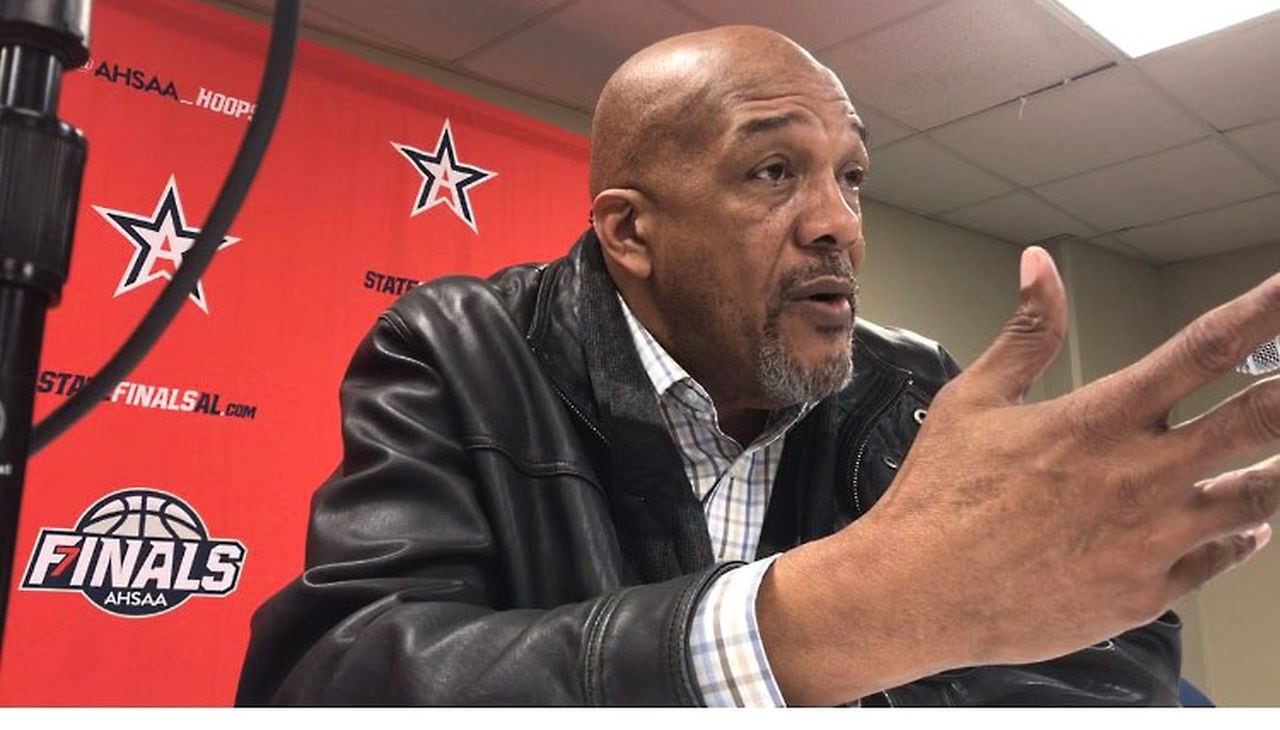

Former NBA and Alabama basketball star Leon Douglas, now 69 years old, has never been about holding anything back, and so he asked a pointed question during the Birmingham Tip Off Club’s get together.

“Why did it take 50 years?” he said to a group of mostly older white men, and the question hung in the air like a jump ball to begin a game.

Better now than never, right?

Douglas, Boonie Russell and Ray Odums were the guests of honor at the Tip Off Club. The reunion of those storied names aimed to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the first time five Black basketball players started a game together in the Southeastern Conference. Douglas, Russell, Odums, T.R. Dunn and the late Charles Cleveland were the players for Alabama in 1973. Dunn, who lives in Charlotte, couldn’t make it down for the talk and Cleveland was represented by his younger brother, Ray Cleveland. Hall of Fame sports columnist Kevin Scarbinsky, one of my journalistic heroes, led the discussion.

I wrote a column in April about Ray’s love for his big brother, and Ray’s quest to have Charles remembered as one of the greatest athletes in state history. The Birmingham Tip Off Club’s meeting was another opportunity to honor the past and reflect on its importance. Cleveland and his Alabama teammates were trailblazers, and that makes them central figures in Alabama’s complicated history of sports and civil rights.

Douglas’ question made me uncomfortable and also made me think. Why are things so slow to resolve in the Deep South? Is it guilt? Politicians? Is it the lingering shadow of generational racism, or maybe just the Southern culture of avoiding awkward moments at lunch?

It took federal mandates to bring Blacks and whites together. That was 60-some years ago, and, if we’re being completely honest, it didn’t really work all that well. Maybe it will be another 60 years from now when the school districts and churches figure things out — that the children are better together than they are apart.

The state and local mandates of Southern apartheid began ending in the 1960s. In the 1970s, sports served as the showcase of the South’s forced social evolution. The 1973-74 Alabama basketball team, coached by the legendary C.M. Newton, went 22-4 overall and 15-3 in the SEC. On Dec. 28, 1973, the group made history when Newton elevated Dunn into the starting lineup in place of point guard Johnny Dill. It gave Alabama the first Black starting five in SEC history. Alabama upset No.8 Louisville that day in the Cardinals’ own holiday tournament.

At the time, Douglas, Russell and Odums didn’t think anything about their places in history. Looking back, they say that being Black Alabama natives playing for Alabama was important to them. That feeling of togetherness makes me proud all these years later.

“We wanted to do something that made a difference,” Russell said.

Why did Newton wait until the game against Louisville to feature an all-black starting five? Perhaps it’s because Newton wanted freshman Dunn to earn the starting role, or maybe it was for a different reason. Louisville featured Birmingham prep basketball standout Allen Murphy. I’ve written about Murphy in recent years, too. Murphy chose Louisville over Alabama, and Alabama’s players believe that it was because Louisville’s recruiters told Murphy that Alabama would never start an all-Black lineup.

Had Murphy gone to Alabama, Russell, Douglas and Odums believe that Alabama would have won a national championship.

Cleveland led the 1973-74 Alabama team in scoring, averaging 17.1 points per game, and the Crimson Tide finished No.14 in the final AP poll of the season. Unfortunately, one of the greatest teams in Alabama history didn’t make the NCAA Tournament. Back then only conference champions made the field. Alabama lost a pair of close games to Vanderbilt and was left out of the Big Dance.

Those narrow defeats still eat at Russell to this day.

“Vanderbilt invented offensive fouls,” Russell said. “I’ve never seen so many players fall so many times.”

Alabama’s “First Five” laid the groundwork for three conference championships. The Crimson Tide won SEC regular-season basketball titles in 1974, 1975 and 1976. Russell went on to play in South America after injuring himself during a training camp with the Lakers. Odums played defensive back in the CFL. Douglas had a long professional basketball career in the NBA and Europe. Dunn played in the NBA from 1977 to 1991 and then coached in the league until 2016. Cleveland, who passed away in 2012, was drafted by the 76ers.

Dunn and Douglas are in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, but their teammates deserve spots, too. Their contributions to the state transcend statistics and championships. Why did it take 50 years for the “First Five” to be honored by the Birmingham Tip Off Club? Douglas’ question will stick with me. There was bitterness there. I’d like to think that things are always getting better, and that one generation shouldn’t be defined by the sins of the ones before it.

It’s more difficult than that, though, and it takes asking tough questions in the hopes of arriving at better answers. Fifty years ago, the “First Five” made history in the SEC. If we’ve come so far, then why are the SEC’s football coaches all white today?

Joseph Goodman is the lead sports columnist for the Alabama Media Group, and author of the most controversial sports book ever written, “We Want Bama”. It’s a love story about wild times, togetherness and rum.