Four generations of Black educators run deep in this Florida community

If you’re looking for an example of Black excellence in the schoolhouse, Mercedes Flowers is the blueprint, honey.

Strict yet soft. Diligent and warm. From 1946-1979, Flowers set the foundation of knowledge for the minds of third and fourth graders at Oakland Elementary in Haines City, Fla. A Talladega College alumna, she reinforced the importance of education while also teaching social studies at Oakland High School, which was attended by Black students across Polk County, Fla. during segregation.

Flowers – lovingly known as “GG” by her family – was particular on how she ran her class. You wouldn’t catch children rippin’, running, hootin’ and hollering in her classroom. Nah. GG didn’t play about that.

Flowers passed away just two years shy of 100 in April 2021. But her legacy inspired three generations of Black instructors in her family who teach in the same school system Flowers once did. Flowers’ children are educators. Her granddaughter, Annatjie Dailey, gives second-graders a sense of joy and structure at Davenport Elementary. Flowers’ great-granddaughter Adaria Dailey will be starting her Associate of Arts degree in education this summer at Hillsborough Community College after two years of being a middle school substitute teacher.

The Daileys’ classroom culture and mannerisms definitely favor Flowers’ way of life.

“She was no nonsense. She had no filter,” Annatjie Dailey said. “She’s gonna give it to you straight. No chaser.”

Interviewing the Dailey family is like attending a comedy show at a family reunion. And Flowers’ sense of humor created an emotional depth with children. Some of Flowers’ former students – who were in their 70s – expressed their appreciation for their former teacher at her funeral. Annatjie Dailey credited Flowers’ upbringing as a child in foster care for why she connected to children the way she did.

“I think that was her way of building that kind of family relationship by having those children and building those relationships,” Annatjie Dailey said.

After graduating college with a business degree, Annatjie Dailey dipped her toe into education by helping out with parental involvement before subbing for about six years. The perks of teaching were the real deal, she said. No night shifts. Weekends and summers off. But like Flowers, the love of children was the selling point when she decided to become a full-time educator. Young students pull on your heartstrings with a hunger for learning, Annatjie Dailey recalls. And to see them grow up is a real treasure.

“It’s full circle,” Annatjie Dailey said. “Seeing those kids as young adults and how much they appreciate your impact on their lives – that’s the real kind of deal with me still living in the town that I grew up in.”

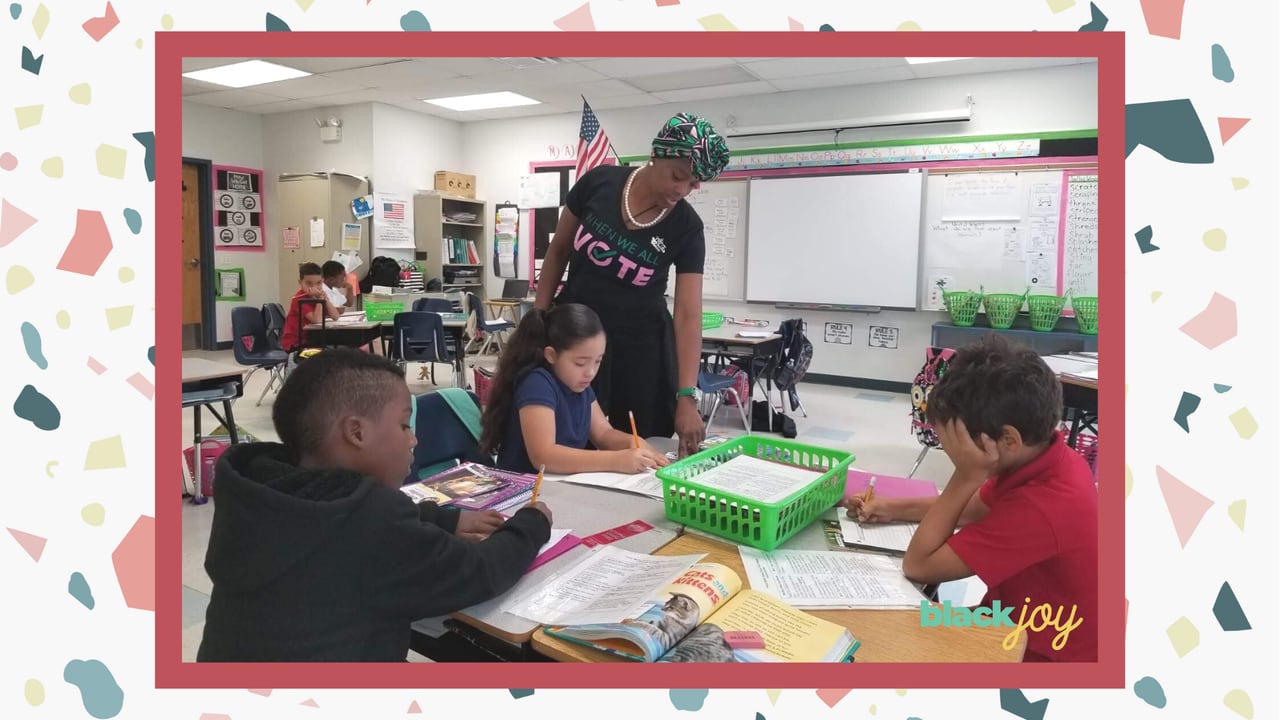

Annatjie Dailey teaching second-grade students at Davenport Elementary.Annatjie Dailey

Like Flowers, Annatjie Dailey is a teacher who runs a tight ship with a loving hand. Shirts are tucked in. Manners are a must in her classroom. Her students know to say their please, thank yous and good mornings. If a child is misbehaving, she doesn’t mind giving that student a firm talk.

“I’m that girl. I’m gonna get you all the way together,” Annatjie Dailey said. “I tell them I’m not the one or the two. So it’s that respect factor.”

Now the rumor mill around school may give her the reputation of being mean, but that’s not the truth. Her softness comes from her playfulness and creativity. After her homeroom received high scores on a national reading assessment test, Annatjie Dailey’s school had her work with students who didn’t benchmark as high. Those kids came into her classroom talking loudly and weren’t attentive at first, but she knew how to get their attention. They were practicing their phonics skills that day. So she asked them to raise their pencils and challenged them to find as many words as they could within two minutes. Ready. Set. Go.

And the whole mood of the classroom changed. Students focused and got on task. Some kids got competitive. Others tried to help out their fellow classmates.

“In their mind, they’re playing a game, but it’s not. I just say that just to get them motivated,” Annatjie Dailey said. “So when they went back to their classrooms they were like ‘Mrs. Dailey isn’t mean. It was actually kind of fun.’”

Both Flowers and Annatjie Dailey wanted all kids to strive for excellence. It didn’t matter if it was her school kids or blood kids. That’s something Adaria can vouch for, albeit with a grimace on her face. Annatjie Dailey had her kids up at 6 a.m. doing reading lessons on an online program called Odyssey before heading to school. And that didn’t stop on weekends or when the school year was over.

“It was the same routine in the summer: 6am. Get on Odyssey,” Adaria Dailey said as her mother cackled in the background. “We didn’t have school. So it went from 6am all the way through to when school would have ended. You know, you get lunch. You get three meals. But you learn something.”

Because of this, Adaria Dailey laughed and said she was traumatized by reading when she was child. But GG’s spirit got Adaria together. She described Flowers’ home as if it were a castle of knowledge. The towering shelves full of books: poetry books, encyclopedias, recipe books. Flowers taught Adaria Dailey the magic of reading by showing her which books to find information. This nurtured Adaria Dailey’s passion to get into education and to teach middle schoolers.

“That’s the age where you truly find yourself going into your preteen/teenage years,” Adaria Dailey said. “You’re figuring out what you want to be in life and what you care about most, you know? That’s the foundation to becoming an adult.”

There was another gift Flowers slid Adaria Dailey’s way: Patience. Which is much needed when teaching middle schoolers. Those kids be wildin’, according to Adaria Dailey, but she stays on her toes in a calm way because who knows what these kids got going on after school.

“School might be their escape and the only time they can really get away from whatever situation they’re dealing with at home,” Adaria Dailey said. “So I’m very patient with my middle school kids because they like to let loose, very just off the wall and I have to get them in check. But then again, I still give them the freedom I feel like they deserve as preteens and teens.”

Politics can pollute the joys of the classroom and oftentimes shoo people away from teaching altogether, Annatjie Dailey said. Educators in Florida are no stranger to this with Gov. Ron DeSantis banning Black history curricula and defunding diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.

But the Daileys pay it no mind. Annatjie Dailey’s students are mostly Hispanic, a gallery of Black authors are still on her whiteboard. She still plans to educate her kids about important Black figures every school day during Black History Month. Even her fashion sense and how she carries herself is an example of Blackness, she said.

“In that aspect, they have a positive Black woman that they see every single day,” Annatjie Dailey said. “I think representation is key in any school where you don’t see that many people who look like you, but when you do see those people that look like you, it’s like, ‘Oh, OK. That’s what I need to see.’”

Adaria Dailey makes it pretty loud and clear that she teaches for the culture no matter where she is or who is in her class. She celebrates Blackness by wearing clothes with Juneteenth colors or anything representing Black culture.

“I’m professional, but I’m not going to change myself just to please others, me personally,” Adaria Dailey said. “When it comes to Blackness, I push it. I tell my kids it’s Black History Month every month.”

Although a teacher shortage is wreaking havoc in all 50 states, Adaria Dailey has hope for her generation in the classroom.

“I feel like a preteen would be more comfortable talking to somebody young like me than, you know, like a 50 or 60-year-old. No shade to them,” Adaria laughed looking at her mother.

“I chose to teach middle school because I want to make an impact on students molding themselves into being great young people,” she continued. “Because I had the best foundation as you can see. Why not spread the love?”