Former officer says prison staffing shortage critical

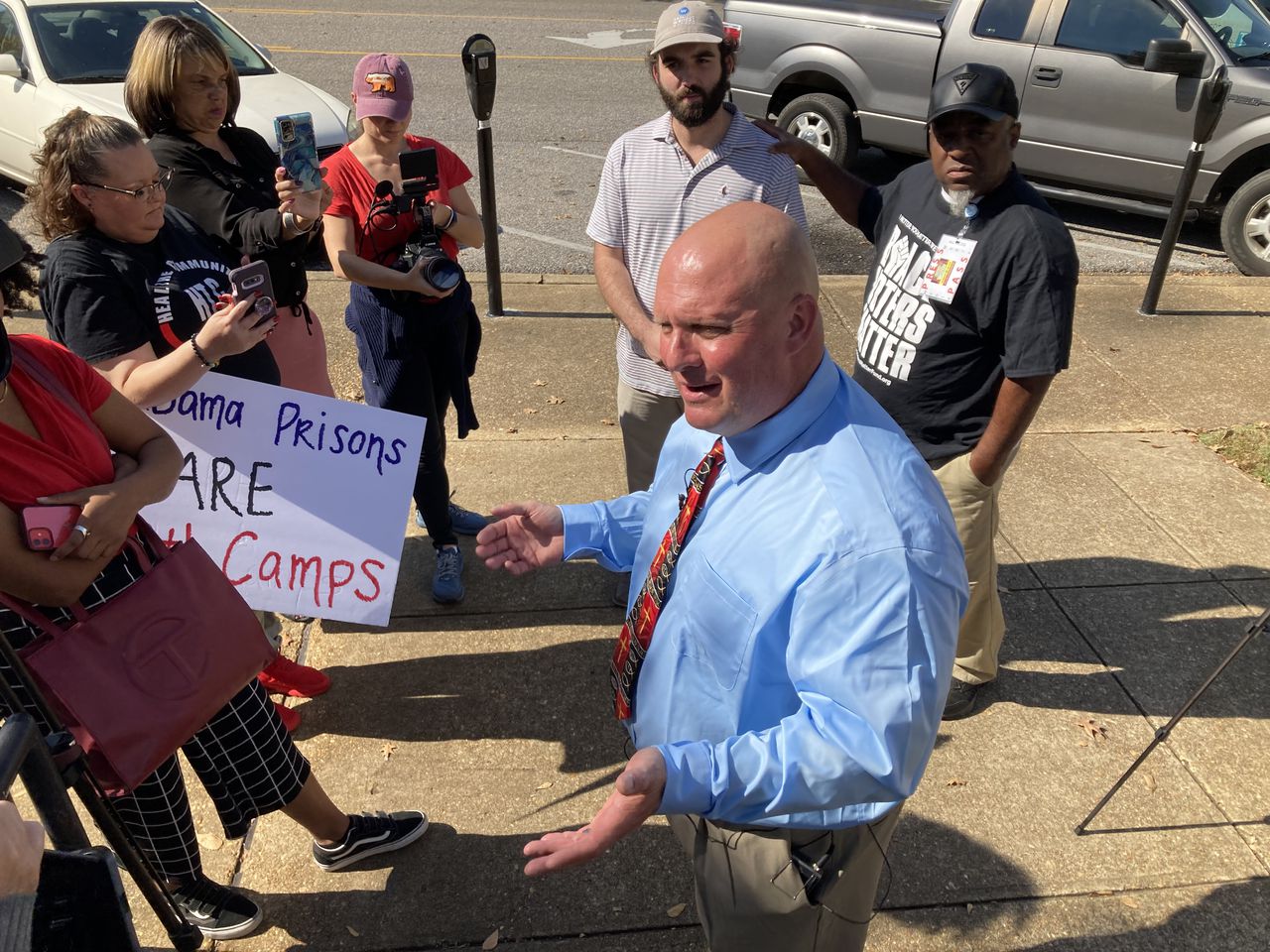

Former Alabama correctional officer Stacy Lee George talked for more than an hour today outside the Alabama Department of Corrections offices, describing what he said is a crisis in the prison system caused by severe staff shortages that put inmates, officers, and the public at risk.

George, 53, who ran for governor this year and in 2014, resigned Oct. 26 because of problems from a back injury suffered in an accident in a prison vehicle last year.

George worked for more than 13 years at Limestone Correctional Facility, the state’s largest prison. Limestone is a “close security” prison, the highest security level, and has about 2,200 inmates.

George said staffing levels have dropped to the most dangerous he can remember. He said it is not unusual to have as few as about nine officers on duty at Limestone, not counting supervisors. He said that number needs to be about 35.

George, speaking to a crowd that included family members of incarcerated men, advocates, and reporters, described a typical day on the job, staring with prayers in in his car on his way to the prison. He described arriving at Limestone to find supervisors scrambling to fill slots for the next shift. George said officers are exhausted after working a mandatory 36 hours overtime a month for almost two years.

“So we walk in, we’re all zombies,” George said. “We’ve gotten four or five hours sleep. And the supervisors are praying to God, probably, if they believe in God. But they’re looking out there even if they don’t believe in God saying, who’s going to come in, who’s going to call in? God help us.”

Alabama prisons have been plagued for years by severe understaffing and overcrowding. The Department of Justice sued the state in December 2020, alleging that conditions for the incarcerated men are so dangerous that they violate the 8th Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishments.

The Alabama Department of Corrections says it is actively engaged in recruiting initiatives for officers, medical and mental health staff. The ADOC has been under a federal court order for several years to increase its staff but is losing ground. A quarterly statistical report showed that as of June the ADOC’s security staff had decreased by 15 percent since September 2021, a net loss of 346 employees.

“I see something that I have not seen before,” George said. “I see the numbers drop down to where it’s dangerous. I see when I come in there’s no life in them. The officers and the lieutenants and the sergeants and the captains, you see a dead man walking. That’s what I was, a dead man walking.”

George said the staffing crisis is creating dangerous situations for inmates and staff and inattention to important safeguards, like checking to see what employees carry inside the prison.

“We didn’t even go through security for months now,” George said. “Walking right through with a bag. You could have carried a 9 millimeter Glock in or a .44 caliber. You could have gotten two or three of them in, because ain’t nobody checking anything at this point. Everybody’s dead. It’s a dead atmosphere this last few months. You just walk right in there.”

George said Thursday the situation is urgent enough to call in the National Guard or State Troopers to help manage prisons. Today, he said he is hoping the Department of Justice steps in.

George said he does not think Alabama’s plan to build two 4,000-bed prisons for men is the right approach to solve the state’s crisis. The Legislature approved a $1.3 billion plan to build the new prisons a year ago. The state has a contract to build one of the prisons, a specialty care facility in Elmore County. There is no contract for the other, planned for Escambia County. Officials have said the prisons are expected to be finished in 2026.

Gov. Kay Ivey and legislative leaders have said the new prisons are part of the solution to the problem, partly because they will be safer and offer better opportunities for rehabilitation, medical care, and mental health care.

George questioned how the state could staff new prisons when it can’t staff the ones it has now.

George said part of the solution is to reduce the number of men in prison, including through paroles. The rate of paroles in Alabama has fallen off sharply in the last few years, particularly after parolee Jimmy O’Neal Spencer was charged with killing two women and a child in north Alabama in 2018. A jury convicted Spencer of capital murder last month. George said Spencer’s crimes were horrible but should not negate a chance for parole for others.

“There’s 20 or 30,000 people in Alabama prisons right now saying we don’t have hope now because of what one man done,” George said. “I’m glad that God didn’t judge me because of what one man done. I’m glad that God above didn’t judge me because of one man making a mistake.”

In describing a typical day on the job, George talked about making security checks where it was not unusual for several men to tell him they were suicidal. He said he saw men wearing nooses and described an inmate cutting his wrist with a razor blade. George said supervisors asked him to make judgements about how serious the suicidal threats were because there was never enough staff or nurses to respond to every possible crisis.

George said he cared about the incarcerated men and never had to resort to using a baton or chemical spray during his 13 years in the prison. He said some officers are not cut out for the job.

“Not everybody needs to have a badge,” George said. “There are people that got beat up in high school and they’ve got a chip on their shoulder. They get a badge and they think that they’re in control of something. And they should have never had that badge. We should be doing mental health evaluations for every officer that hires in at Limestone prison.”

George said the staffing shortage sometimes means that inmates don’t get their medications on time, including those with conditions that need close monitoring, like diabetics. George said he kept a piece of candy in his pocket and carried in peanut butter sandwiches for the incarcerated men.

The ADOC said in a statement Friday it would not comment on George’s statements about staffing.

“Staffing is the subject of ongoing litigation and court orders,” the ADOC said. “Additionally, disclosure of specific staff numbers at a facility creates the risk of a security issue. For these reasons, the Department is unable to comment on specific staff numbers and/or implications.”

As for the security risk, George said the short staffing is well known to inmates.

“The incarcerated individuals already know how many officers are there,” George said. “They know what we’re going to do. They know which way I’m going to walk when I leave that cube. They know what I’m going to do. They know that there’s only six or seven officers at times. Or eight or 10, whatever it is. But the public needs to know.”