Former Alabama linebacker Darwin Holt has died

Darwin Holt, an undersized but fierce linebacker on Alabama’s 1961 national championship team who was at the center of one of the most controversial plays in college football history, has died. He was 84.

Holt’s death was confirmed to AL.com by Tommy Ford, retired director of Alabama’s A-Club Alumni Association. No other details were immediately available.

Listed at 5-foot-10 and 172 pounds but probably smaller, Holt was a key part of an Alabama defense that allowed just 25 points in 11 games in 1961. The Crimson Tide went undefeated and won the first of six national championships under Paul “Bear” Bryant that season.

In time of “iron man” football at the college level, Holt played only defense and special teams. He would typically replace the Crimson Tide’s quarterback — usually Pat Trammell — in the lineup, and with All-American Lee Roy Jordan formed one of the top linebacker duos in the sport at the time.

“We had six shutouts that year,” Holt said in a 2018 interview with AL.com. “Our defensive record, I wish they’d put it on the wall down there and let them shoot for it.

“Georgia scored a touchdown on us, but they were already beat, so they didn’t kick the (extra point). Vandy scored two field goals on us. North Carolina State … scored the only touchdown of the year against us. Tennessee kicked a field goal. No one scored the rest of the year until Arkansas scored three points on us.”

A native of Gainesville, Texas, Holt first signed to play for Bryant at Texas A&M, but Bryant left for Alabama after Holt’s freshman year. He transferred to junior college for a year before re-joining Bryant with the Crimson Tide.

Holt told AL.com in 2018 that left Texas A&M in part because “there were no girls there,” but also because he longed to play again for Bryant. However, the coach feared he would be accused of tampering if Holt following him immediately to Tuscaloosa, so Holt instead spent a year at Gainesville Junior College and then reunited with Bryant at Alabama.

“Some years later Jim Myers, the coach at Texas A&M and later with the Dallas Cowboys, he was at a reception,” Holt said. “He saw me across the room and he said ‘you tricked me, you tricked me, you son of a gun.’ I said ‘Naw, coach. You were so happy to get that scholarship back, you couldn’t stand it.’”

After missing the 1959 season due to injury, Holt started for an Alabama team that finished 8-1-2 and tied Texas in the Bluebonnet Bowl in 1960. The Crimson Tide began the 1961 season with eight straight victories — the first-team defense allowing just one touchdown in that span — heading into a Nov. 18 showdown with Georgia Tech on Nov. 18 at Birmingham’s Legion Field.

It was during the fourth quarter of that game — a 10-0 Alabama victory — that Holt was involved in the play that would define his career and his legacy. While blocking on an Alabama punt, Holt delivered a forearm to the jaw of Georgia Tech halfback Chick Graning — a move that was either violent-but-clean or outright dirty, depending on one’s point of view.

Graning suffered severe facial injuries on the play, including a concussion, a fractured nasal bone and several broken teeth, and was hospitalized for a time. Holt said he visited Graning in the hospital and apologized, but the incident soon took on a life of its own.

Georgia Tech coach Bobby Dodd decried the play as an example of the brutal tactics taught by Bryant, and demanded that the Alabama coach suspend Holt. Bryant refused (as many have noted, Holt was not penalized on the play), drawing the ire of not only Dodd, but many in the media.

The Atlanta newspapers in particular were outraged. Atlanta Constitution Jesse Outlar called for Holt to be kicked off the Alabama team, while Furman Bisher of the Atlanta Journal described Holt as a “little ruffian from Gainesville, Texas” who would have been “jailed and prosecuted” had he hit Graning in such a fashion on a street corner rather than on a football field.

The issue was further inflamed the following fall, when Bisher wrote an article for the Saturday Evening Post entitled “College Football is Going Berserk,” laying the blame for much of the sport’s brutality at the feet of Bryant and the Crimson Tide. Dodd was quoted extensively in the story, implying that Bryant and his Crimson Tide coaches taught “dirty” tactics. (It would not be the last time Bryant was attacked in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post.)

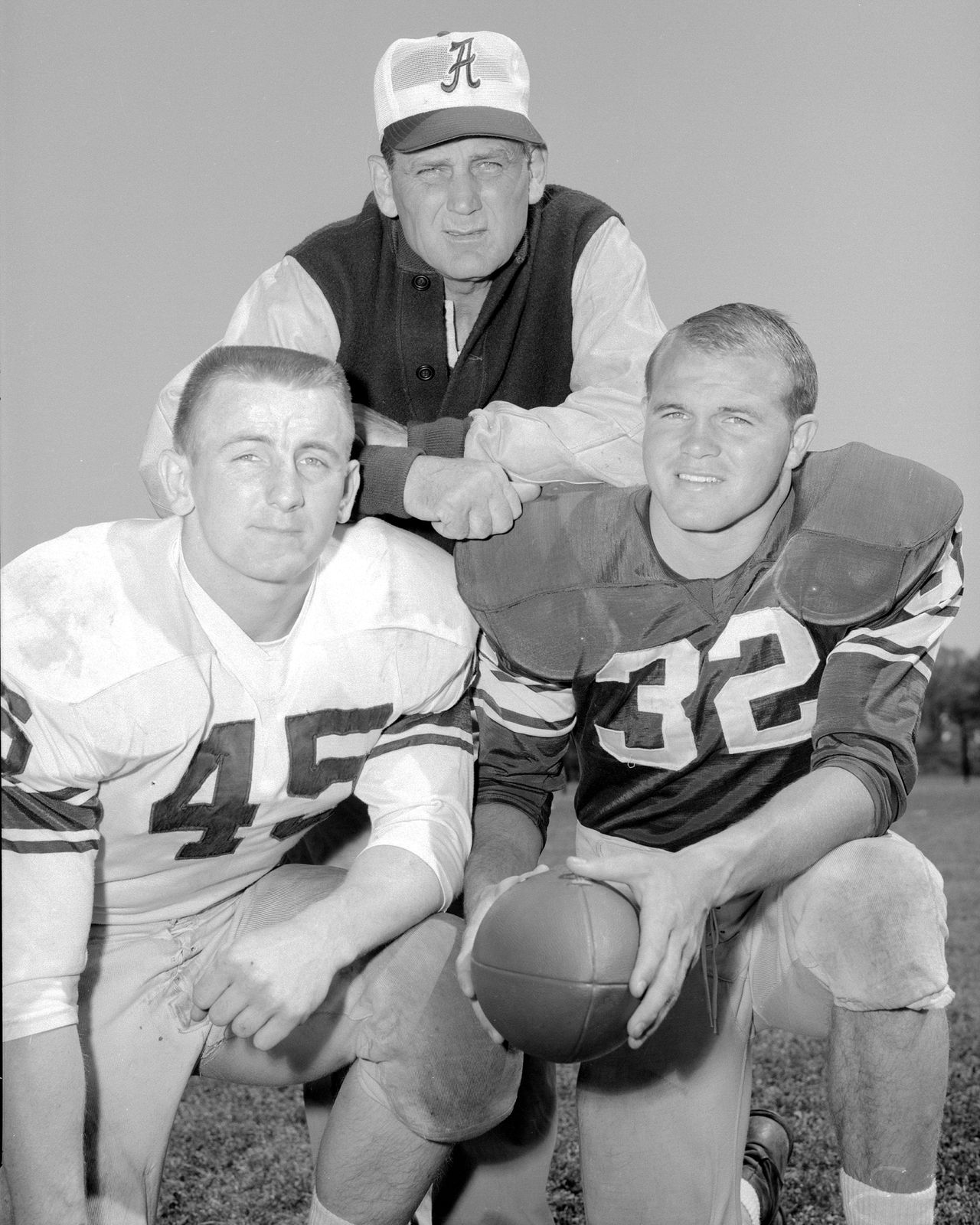

Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant is shown with Elbert Cook (45) and Darwin Holt (32) in 1961. Holt died this week at 84. (Photo courtesy of the Paul W. Bryant Museum)

Bryant discussed the Holt-Graning incident and its aftermath at length in his 1975 autobiography “Bear,” written with John Underwood. He believed that critics were attacking one of his players as a way of attacking him.

“There’s no doubt Darwin fouled Chick Graning, and the officials should have penalized us, which they didn’t,” Bryant wrote. “But it could have been anybody in the secondary, not just him. I probably would have disciplined him my own way if those Atlanta sportswriters hadn’t set out to crucify him. A penalty is one thing, a crucifixion is another. After that I wouldn’t have done anything if they had burned the university down.”

The Holt-Graning affair also damaged the friendship between Bryant and Dodd, and led indirectly to Georgia Tech leaving the SEC at the end of the 1963 season. The Crimson Tide and Yellow Jackets played through 1964, but wouldn’t meet again until 1979, by which time Dodd had long since retired.

Speaking to AL.com nearly 60 years later, Holt said he believed the incident also caused him not to be named to the All-SEC or All-America teams. He continued to insist he didn’t intend to injure Graning.

“It was a legal block,” Holt said. “The official was looking at it — he saw it. And what happened … it was a punt return. I called ‘punt return right.’ … On punt return right, I’m to take the end man on the line of scrimmage and follow him down the field. The end man is going to turn everything in. He’s going to go as deep as the ballcarrier. What I’m to do is stay three yards inside of him, two yards behind him.

“Then when (Graning) makes that 90-degree turn, I’m supposed to come up under his inside arm and hit him high and drive him out. The ballcarrier cuts in behind me to get behind the wall. He comes by me, I release the guy and follow the runner down the wall in case someone broke through the wall behind him. That’s the rule, it’s in the books. That guy just happened to be end man on the line of scrimmage. If they bothered to look at the film — I’ve got the film, (Bryant) gave it to me — you’ll see what happened. When he picked me up, you can see his right leg bend. He bent. And when he bent, that was the six-inch difference between hitting him in the chest and hitting him in the jaw.”

The victory over Georgia Tech lifted Alabama’s record to 9-0, and the Crimson Tide finished the season with wins over Auburn (34-0) and Arkansas (10-3). The team was voted No. 1 in both the Associated Press and United Press International polls.

After graduating from Alabama, Holt stayed in football for a time, playing in the Canadian Football League and briefly coaching at New Mexico Military Institute. He told the Birmingham News in 2003 that he always wanted to be a coach, but that the incident with Graning forced him to leave the game and enter the regular working world.

“I knew that if one of my players ever hurt anybody, they would say that I had taught them to do that,” Holt said in 2003. “So, I gave up coaching and got into business.”

Darwin Holt is shown with former Alabama teammate Tommy Brooker in 2008. Holt, a key member of the Crimson Tide’s 1961 national championship team, died this week at age 84. (Birmingham News file photo)bn

Holt spent most of his working career in insurance management and later in marketing for a heavy equipment company, living at times in Arizona, Texas, Louisiana and South Carolina before returning to Alabama. He lived his last several years in the Birmingham suburb of Vestavia Hills.

When interviewed in 2018, Holt spoke with pride about the fact that both his daughters also graduated from Alabama, with their schooling paid for through the Bryant Scholarship program. Bryant founded the program shortly after Trammell’s death at age 28 in 1968, with any children of his former players permitted to attend the university tuition-free.

“I love Alabama,” Holt said. “I love the people of Alabama. Wherever I’ve been transferred to with my companies, I’ve always wound up back in Alabama. … That was the wisest move I ever made, the best letter I ever wrote, to come out here with (Bryant). He was my kind of man.”

Funeral arrangements were incomplete as of Thursday morning.