Fire school is in session: Control burn trainees in Alabama learn to use fire as a tool

Sometimes it can be productive to burn. Sometimes it can even be a career.

For those who do want to earn a living using a drip torch, The Nature Conservancy in Alabama offers yearly training in prescribed fire work that includes hands-on field experience at controlled burn sites across the state.

Periodic controlled burns are an essential part of managing forest land, to keep debris from piling up too high and fires from burning too hot when they do occur. Alabama’s disappearing longleaf pine forests are especially dependent on periodic fires, which would have occurred naturally, but are now provided by crews working in helmets and flame-retardant clothing.

“There’s no other thing that humans can use that’s as applicable on a broad scale, and as beneficial when done correctly, as fire,” said Geoff Sorrell, an ecologist for The Nature Conservancy and “burn boss” for one of the training sessions.

The Nature Conservancy in Alabama has hired and trained fire crews since 2004, and now burns about 60,000 acres each year in the state.

Sorrell said those seasonal workers can build their resumes while helping restore one of Alabama’s most imperiled ecosystems.

The Nature Conservancy in Alabama conducts training on controlled burns in Bibb County, Ala. for those interested in using fire as a land management tool.Dennis Pillion | [email protected]

“If they like this kind of work, and they like being out in the smoke and the dirt and the sweat, then they might be looking to go out west this summer where there’s a lot of seasonal fire staff,” Sorrell said.

From there, the possibilities expand further, working for agencies like the U.S. Forest Service, or state forestry commissions or non-profits like The Nature Conservancy. But the key is to get trained and go out West, Sorrell said.

“That is really the backbone of the workforce, the summer wildfire season across the western U.S., and there there’s many thousands of jobs that are seasonal out there,” Sorrell said. “That’s the way to get in with a federal agency. A lot of state agencies field summer seasonal crews as well. And from there, they can try to find more permanent jobs and it could go in a whole number of directions.”

Some of the trainees are hoping for a career out of the training. Some work desk jobs for The Nature Conservancy, but are getting their certification to help out on burns from time to time and escape the daily grind.

It’s one of the perks of working for the group, said Mitch Reid state director for The Nature Conservancy in Alabama. The training also helps the group accomplish its mission to conduct regular burns every few years to help bring the longleaf forests back.

31

The Nature Conservancy controlled burn training

Why burn?

Fire is natural and necessary. Lightning strikes can ignite leaf litter on the forest floor, clearing out the underbrush without killing the trees.

Longleaf pine forests are especially dependent on fire. The flames actually cues the longleaf seedlings to start growing, a natural reminder that the brushy competitors have been cleared out and it’s time for the trees to take over.

Longleafs are slow-growing trees that can survive for hundreds of years. Mature longleaf stands feature an open canopy of trees, well spaced apart, with shorter grasses underneath. The forests are home to such imperiled species as the red-cockaded woodpecker, the gopher tortoise, and the eastern indigo snake.

These forests once covered much of Alabama and the Southeast in general, but is now mostly found in isolated pockets of protected land in national forests or state parks. Early settlers reported being able to easily navigate their wagons through the heart of these longleaf forests because the trees were so distant.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that longleaf forests once covered 90 million acres from Virginia to Texas, but was cut back to about 3.2 million acres before restoration efforts took hold.

Young longleaf pine trees sprout up over grasses at the University of West Alabama’s Cahaba Biodiversity Center in Bibb County, Ala. Dennis Pillion | [email protected]

Many of Alabama’s pine forests now are created for the timber industry, with loblolly pines or a similar fast-growing species packed as densely as possible by tree farmers to harvest the wood in 20 or 30 years.

The system works well for the landowners in turning a profit but doesn’t do much for the native wildlife. By restoring more pockets of longleaf forest, groups like The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others hope to revive an ecosystem that was on the verge of being wiped out.

Reid said regular burns will help restore the forests to their natural condition.

“As we burn, you should see that forest open up,” Reid said. “You should see longleaf pine come in and replace the loblolly.”

Their first fire

As part of the training, The Nature Conservancy took 10 trainees, five full-time TNC employees and one AL.com reporter into the University of West Alabama’s Cahaba Biodiversity Center in Bibb County.

The Center hosts groups of biology students from UWA, about a 90-minute drive, to learn about the longleaf ecosystems and the Cahaba River, which flows past a house on the property. TNC is working to perform controlled burns and land clearing on areas where thick stands of loblolly pines were planted to restore the more open longleaf forests that dominated the area before human intervention.

It’s a relatively small area and a good one for the new trainees to experience their first prescribed burn.

The day starts with a briefing from Sorrell, the burn boss, on the day’s activities. He quizzes the trainees on things they should know about the site they’re about to burn: what’s the wind speed and direction; where are the trucks with emergency water and medical supplies; where are the safe zones that won’t be overrun by fire; where is the nearest hospital; the nearest highway; where can a helicopter land in the event of an emergency.

Part of the training, as important as how to set a fire, is to show people how to be aware of their surroundings and to have plans in place should something unexpected happen.

“There’s so many things that I want these people to learn to think about,” Sorrell said after the briefing. “And the situational awareness on the fire line is different than if you’re going out for a hike or you’re cruising down a backwoods road.

“A lot of people in this day and age that we train, they don’t even have that kind of experience. They have not spent time in the outdoors. And so we’re taking folks with a variety of backgrounds, and we’re sometimes introducing them to an entirely new world and then we’re teaching them how to safely use a tool that most people are afraid of.”

The trainees spent the previous day prepping the area for the burn — clearing fire breaks and setting up water pumping stations — but for most of them, it’s their first time actually participating in a controlled burn.

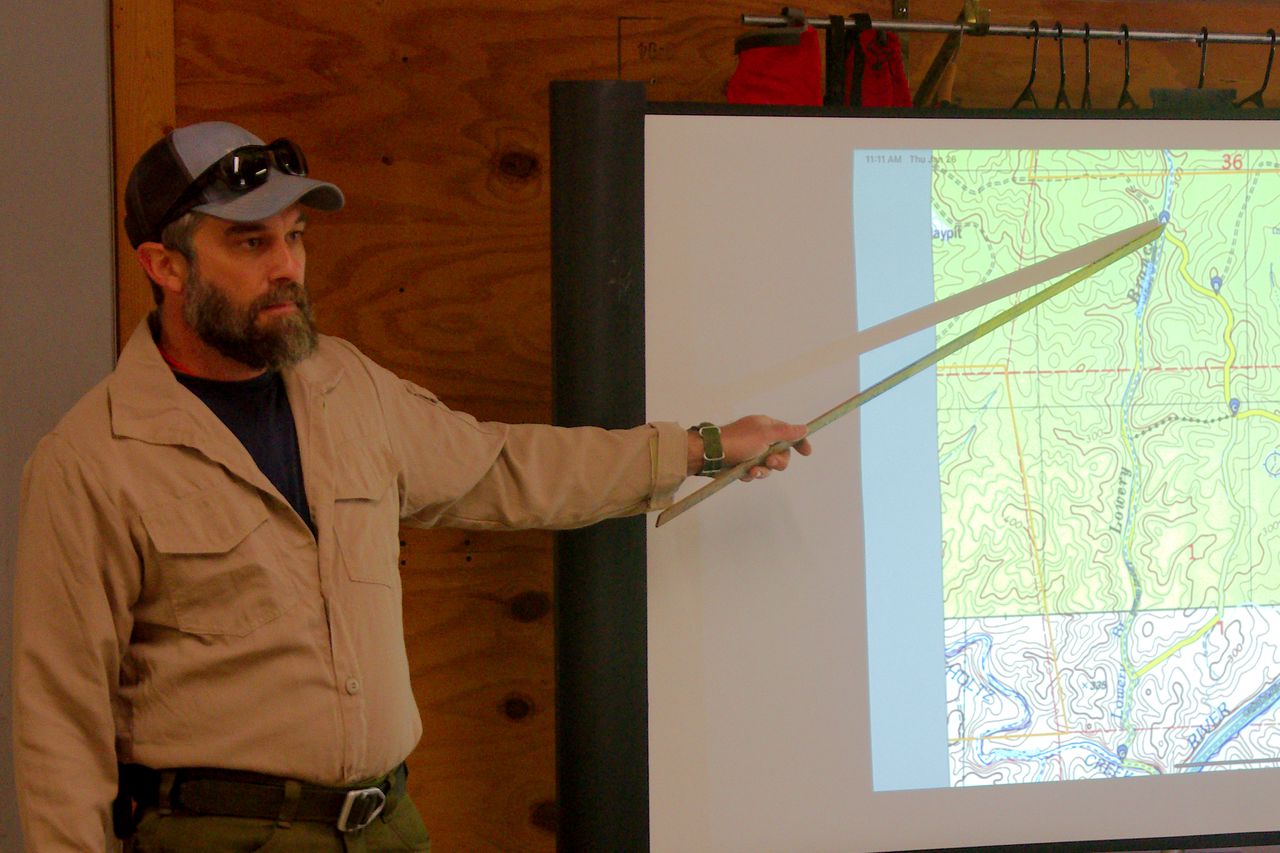

Geoff Sorrell conducts a briefing before a controlled burn at the University of West Alabama’s Cahaba Biodiversity Center. Dennis Pillion | [email protected]

Sorrell points to a map of the 70-acre area being burned today, with checkpoints marked Alpha through Juliet.

The participants are split into groups with an experienced leader to direct operations in radio contact with the burn boss. Each team is given their assignments around the perimeter of the area.

All fire personnel are decked out in thick gloves, boots, hardhats, eye protection and the trademark flame-resistant yellow shirt and green pants of the prescribed burn trade.

The tools of the trade are fairly standard: A variety of specialized rakes, shovels and hoes to clear the brush where needed and a drip torch to provide the flame.

The drip torch has a wick that stays lit while in use and a long metal tube that drips a mixture of diesel fuel and gasoline over the wick.

The diesel burns longer, but it needs a little gasoline to make it easier to light, said Chuck Byrd, stewardship coordinator for TNC, and one of the veterans in the crew.

The Nature Conservancy in Alabama conducts training on controlled burns in Bibb County, Ala. for those interested in using fire as a land management tool.Dennis Pillion | [email protected]

I’m observing with Sorrell and Byrd, and two groups of trainees working between points Alpha and Bravo, moving south and west, toward the center of the burn area.

It takes the trainees some practice to get the hang of the drip torch. You’re not really trying to make a full line of fire, Byrd says, but just drop enough fuel mixture to catch the fallen leaves and pine straw that cover the ground in between the trees. The flame will fill in the gaps once it gets going.

Some trainees drip too much fuel, sloshing unburned liquids around and some are having trouble getting the thatch to catch. To move on to another area, the trainees just grab the wick with their gloved hand, snuffing the flame out until they’re ready to light it again.

It’s not the ideal day for a control burn for ecological purposes, Sorrell said. It rained the previous morning, and things are still a little damp in the shade. But that’s not the worst thing in the world for a bunch of first-timers and a crew that’s never worked together before.

“This is a pretty mellow burn day,” Sorrell said. “Fire behavior is to the point where it’s burning, but in some places not real readily. And to get people running a drip torch, thinking about all the potential hazards of fire management, this is a good day for that.

“If it was burning better, we’d still be out here doing training burns, because I have a good, a good cadre, a good network of folks that have a lot of experience. So even under different conditions, we can keep people safe.”

Just as he said, the burn is pretty mellow. There’s a lot of standing around, watching low flames creep along the ground, turning leaves and pine straw into ash while the green needles of sapling pine trees are unaffected. A controlled burn is a slow one, and once the fire is started, you’re just an observer, making sure nothing unexpected happens.

Sorrell said the area has been burned before, probably about five or six years ago, based on the vegetation. Ideally, he said, it would be burned every two to three years, to keep the creeping muscadine vines and sweet gum trees at bay while the longleaf grows back.

The trainees will be working through May on controlled burns across Alabama in places like Talladega National Forest, Conecuh National Forest, Flagg Mountain, Splinter Hill Bog Preserve and the Cahaba National Wildlife Refuge. That’s when the training ends, and those who want to continue with their fire education can do so.

Across the road from the day’s burn area is a budding longleaf forest, with young, well-spaced longleaf trees sprouting 6-10 feet over a grassy savannah. That area is scheduled for burning this year too, but not for the first-time crew. Those grasses will go up quickly, leaving the new longleafs unscathed and perhaps triggering some new seedlings to start growing.

Eventually, the idea is to create enough connecting parcels of longleaf forest to allow those forests and the unique creatures that live in them to come back from the brink of extinction.

“Over time, it’ll be a picture into what Alabama used to be and what it still can be with proper management,” Reid said.