DNA cross-referencing technology used on unidentified migrant remains to locate mourning families

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

The portion of Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson, Arizona where deceased migrants whose remains are not claimed by their families are buried. Photo by Andrea Godínez.Photo by Andrea Godínez.

A person ventures into the desert, walking for miles and miles through the dust and past snake burrows, hiding from the helicopters, motorcycles, and border police vans that hunt them down. As they enter inhospitable lands, their clothes become covered with cactus thorns, each as thin as a hair yet sharp as a needle. Carrying as many water bottles as possible, they know they won’t be enough to make it the whole way. They cross the scorching desert for days, weeks, and when the sun goes down they look for a tree, perhaps a mesquite, and fall asleep hugging their own legs.

A person who goes into the desert to get to the U.S., whether they suspect it or not, may die trying. If that happens, in a few days their body, their name, their country, their history, are erased until they become bones.

The place where they die and where their bones fall determines their chances of recovering their identity and returning to their family.

In recent years, the use of DNA has made it possible to identify migrants who died even 30 or 40 years ago. Scientifically, this is no longer a problem. The difficulty lies in the dearth of economic resources to perform the tests, the barriers to cross-reference the DNAs of the families with those of the persons found, and the lack of unified protocols when a body is found in a border county.

To die in Arizona

Since the 1990s, the primary routes that migrants use to enter the U.S. have run through two states: Arizona and Texas. The chances of identifying the remains of migrants who die differ depending on which route they take.

Arizona has only four counties bordering Mexico: Cochise, Pima, Santa Cruz and Yuma. All but Yuma rely on the Pima Medical Examiner. This means that the remains of missing migrants are highly concentrated in that coroner’s office.

Gene Hernández speaks with his hands entwined, sheriff’s badge around his neck, in broken Spanish: “When I started here I was the only person who spoke Spanish,” he says. Today he is the supervisor of medicolegal death investigators for Pima County.

Gene Hernández, forensic examiner at the Pima County morgue, inside the trailer that holds the remains of migrants who perished along the border. Photo by Andrea GodínezPhoto by Andrea Godínez

Gene’s last name, Hernández, comes from his father, a Mexican migrant who made his way into the U.S., probably with the same hopes of those who are now sitting in the boxes Gene works with. Gene was born in the US and learned how to speak Spanish after marrying a Mexican woman. His father barely spoke to him in his language when he was a kid.

For a long time, Gene was in charge of contacting the migrant’s families after they were identified. He says that, in 22 years of work as a forensic examiner, the case that struck him the most was when they found two bodies together: a Guatemalan mother and her daughter. There were only bones left of them.

His office could be that of a movie script writer; He has photos with posters of film productions he has been part of such as “The Undocumented”, “NarcoCultura,” as well as hundreds of objects: a blue chair with a caricature of Dick Tracy, the famous police investigator of the American comic strips; a shelf full of dolls portraying baseball, basketball and soccer players; his business cards, wedged between the teeth of a card holder that simulates the skeleton of a jaw; a cork board with a photo of him and his wife dressed as John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

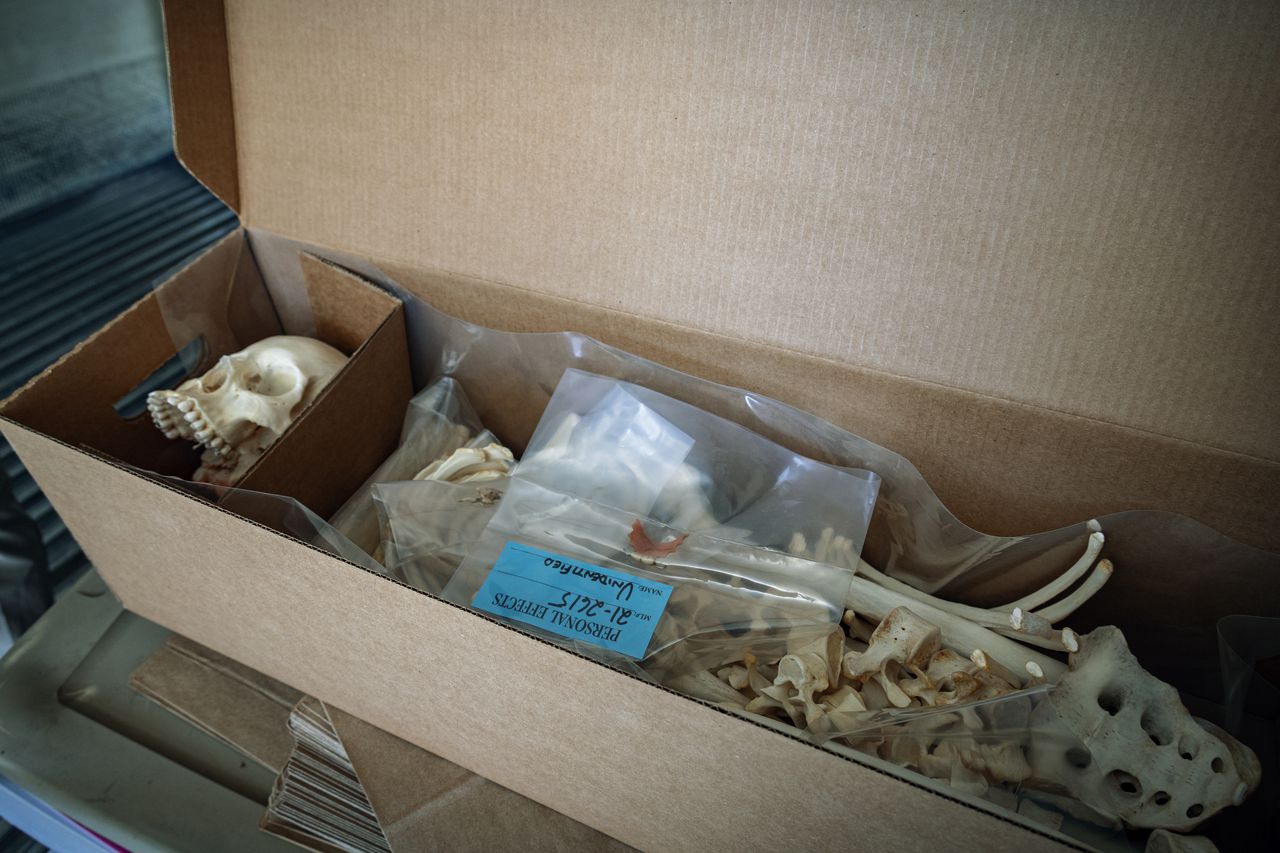

Gene’s office opens onto a hallway that leads to a parking lot, where a trailer has been parked for more than ten years. The coroner opens the trailer’s two doors, brings down a folding ladder with three rungs, places it on the floor next to the edge and climbs up. Inside the trailer, he gets lost among the rows of cardboard boxes stacked one on top of the other, from floor to ceiling. There are 200 of them: In each box there may be the bones of one or two people.

For each box there is also a family waiting, in some country south of the U.S.

A trailer parked outside the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner that stores boxes with the remains of migrants who died in the desert. Photo by Andrea GodínezPhoto by Andrea Godínez

She didn’t bite her nails

Bodies in the desert deteriorate quickly, becoming nothing but bones in less than a week. That not only makes identification more complex and more expensive, but also leaves families with many questions.

“They don’t want to believe that it’s possible that they talked to their sister four weeks ago, and now you’re saying that all that’s left of her are bones,” Gene explains. “They say, ‘she had a mole on her nose’ and it’s hard to tell them there’s no nose anymore.”

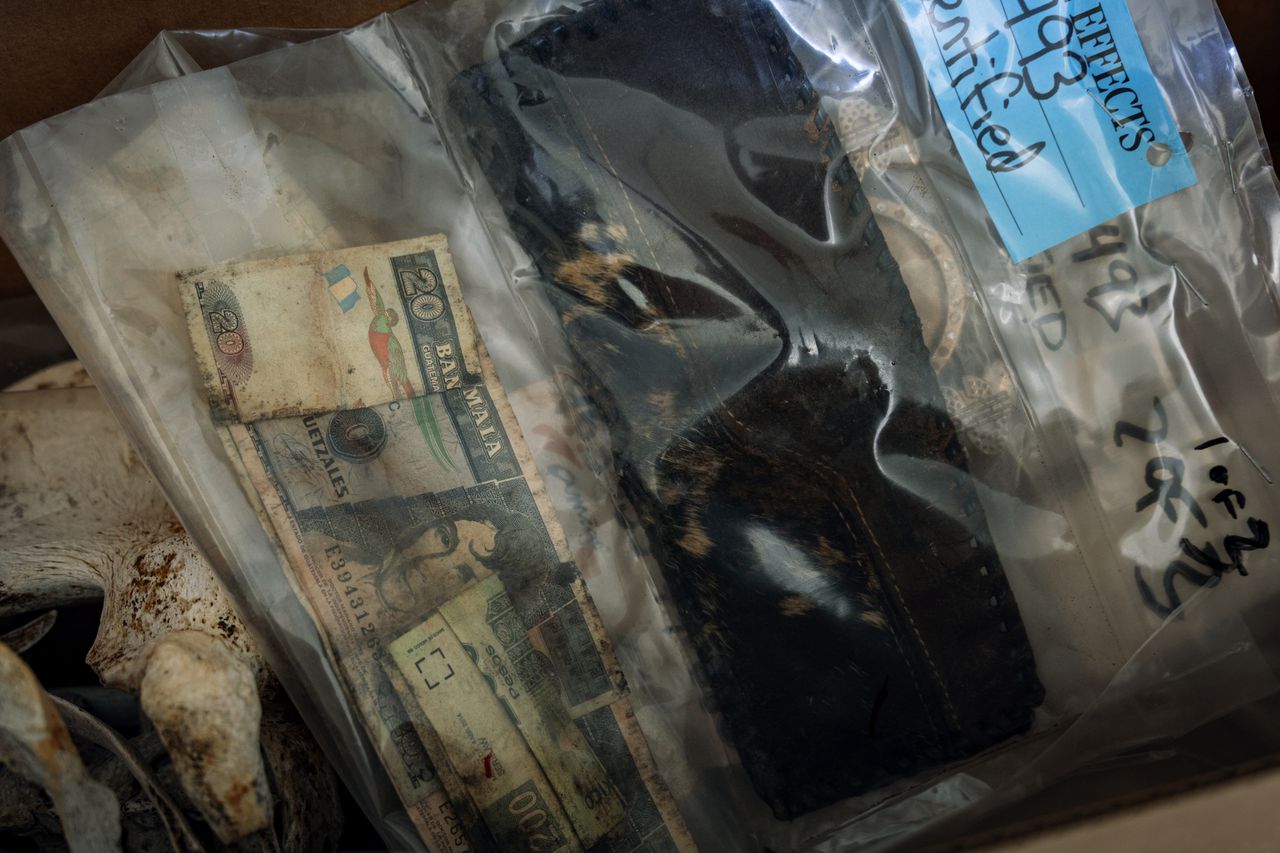

In the boxes of the trailer at the Pima morgue, along with the bones, are the migrants’ possessions of the migrants: tattered clothes, dried out sneakers, rusty belt buckles, images of the Virgin Mary with a prayer on the back, bills, cell phones, small pieces of paper with phone numbers.

NamUS Case 21-0493. The remains of a man between the ages of 25 and 45 found in Big Fields Village, Arizona. Photo by Andrea GodínezPhoto by Andrea Godínez

“The remains come in through different organizations. They notify the authorities and (the authorities) notify us. It could be the Pima County Police, the Tohono Oʼodham (a local Native American community), or the Border Patrol,” explains Gene.

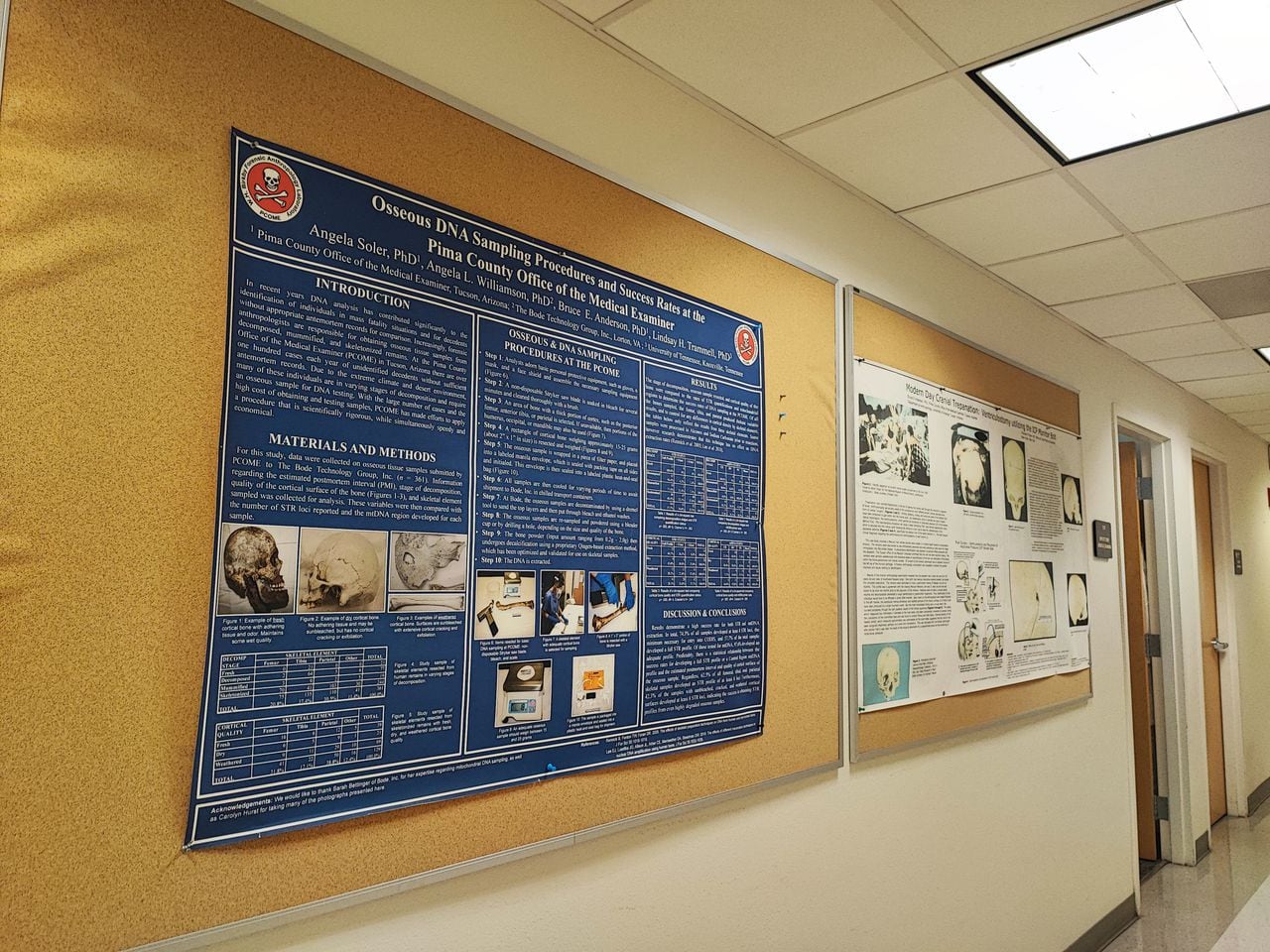

After Gene’s office receives the remains, each is assigned a case number that becomes the only way they will be referred to until identification is achieved. Forensic doctors perform the first examination. Then the anthropological specialists try to determine the age of the individual, the gender, and how and why they died, if that can be determined. All this information is uploaded to NamUS, a free online database that any member of the public can access.

From there, the hardest work begins: finding the families.

Robin Reineke, then a graduate student in cultural anthropology at the University of Arizona, began an internship with Dr. Bruce Anderson at the Pima Medical Examiner’s Office in 2006. She discovered that families of migrants would call daily and the office staff would write up unofficial “courtesy reports” that contained not only the usual information, such as name, age, date last seen, but also handwritten notes in the margins that said, “She was a good person,” or “She didn’t bite her nails.”

Each year, there were between 350 and 400 reports, mostly handwritten, and the staff couldn’t keep up. So Robin began to digitize everything. “What I learned during this process was that the families wanted a faster and better system to search for the missing. They were tired of calling dozens of state offices and NGOs, always giving the direct or indirect feeling that they were calling the wrong place. They wanted to be able to send their DNA to compare with the unidentified dead, and they wanted to meet other families,” writes Robin Reineke in the academic article “Forensic Citizenship Among Families of Missing Migrants on the U.S.-Mexico Border,” published in the journal Citizenship Studies in 2022. That’s how Reineke ended up founding the Colibrí Center, an organization that supports Pima forensic scientists in the search for families’ DNA in their countries of origin.

Nowadays, the process looks like this: If the body is in a proper condition, fingerprints are collected and a search is conducted to see if there is a match in the Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS). If the person was ever arrested at the United States border, for example, their data should be on the records and used for identification.

Case number 21-2565, a woman found in June of 2021 in San Miguel, Arizona. Photo by Andrea Godínez.Photo by Andrea Godínez

If there are no fingerprints, because the remains are too degraded, and there is no way to make a quick identification, Colibrí is notified. The organization is in charge of tracking down the family to obtain DNA samples. The more samples they receive from immediate family members, mother, father, siblings, the greater the chances of a match.

If the relatives are in the U.S., the Colibrí team tries to collect the samples or asks people to send them by mail. On their YouTube channel, they have tutorials that offer instructions. One challenge they face is that in some cases these relatives don’t have an immigration status and are afraid of being deported if they approach the authorities.

In these situations, Colibrí assures the relatives that the organization will not report them. “We have a code in our database so that the names of people who submit DNA are not accessible to the doctors at the forensic office, nor to any organization,” explains Mirza Monterroso, director of the Missing Migrants and DNA project at Colibrí Center.

If the family members are outside the U.S., Colibrí contacts the network of ally social and family organizations, such as the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), the Community Studies and Psychosocial Action Team (ECAP) in Guatemala, the Foundation for Justice (FJEDD) in Mexico, among others, to coordinate the collection of samples. Sometimes, when possible, someone from their own team travels as well.

“The focus of our program is to take DNA from families who have not found their loved one and compare it with all the samples in the lab,” says Mirza Monterroso, referring to Bode Cellmark Forensics, a private lab in Virginia where Pima County processes its samples. “From this forensic office alone there are about 1,300 unidentified person profiles,” she adds.

Hallways at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner that lead to the trailer that holds the remains of migrants. Photo by Andrea GodinezPhoto by Andrea Godinez

There are few laboratories that perform these tests and in recent years their prices have risen significantly. Each bone sample for genetic cross-matching can cost $1,375. Add to that the cross-matching with the family’s DNA and the report can cost up to $4,000. Colibrí covered the costs of DNA cross-matching thanks to the economic contribution it received from the Mexican government, in addition to the grants and philanthropic funding they were able to raise.

300 families still waiting

Identification was faster seven years ago. As it was known that 80% of the migrants who died at the border were Mexican, the Mexican government allocated a budget for identification. But as of 2016, according to Colibrí, that funding was discontinued. .

Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was asked to report on the agreements it has with agencies for the identification and repatriation of bodies, as well as the annual budget allocated to send remains of immigrants from the U.S.to Mexico. Through the response obtained from requests for access to public information made by this team, it was evident that the Ministry has been reducing its budget for repatriations in the last nine years.

The organization Colibrí Center collected, in the last five years, 1,888 family DNA samples corresponding to 854 cases. Those numbers change constantly as more bodies arrive and more DNA is sought.

But when Mexico broke the contract with the laboratory, the DNA cross-referencing process began to slow down. “Today we have a backlog of 300 cases that are not in the lab. There are many people we are looking for who may already be there but have not been identified,” explains Mirza Monterroso.

“It is very difficult to explain to the families how unfair it is that there is no money to process the samples,” she says. Migrants, missing for their families and dead in a box, are still waiting.

Case number 21-2615, a woman between the ages of 18 and 30 found in San Miguel, Arizona. Photo by Andrea GodínezPhoto by Andrea Godínez

When ranchers call

The situation in Texas is different. First, unlike Arizona, which has only four border counties, there are 32 border counties in Texas. All of them are considered border counties because the state has a double checkpoint: in addition to the counties on the geographic border with Mexico, there is a second checkpoint 60 miles inside the national territory.

Many migrants cross the border while trying to circumvent that second checkpoint, crossing expanses of private land, and die along the way. In those cases, recovering the body depends on local ranchers finding them and alerting the authorities. Many times they fail to do so.

As of 2021, migrants started to cross the border near the Texan cities of McAllen and Eagle Pass, where the deaths of Mexican immigrants increased, according to databases kept by the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Office (CBP).

On the other hand, the report “Migrant Deaths in South Texas,” by the Strauss Center at the University of Texas at Austin, insists that border patrol underreports migrant deaths in South Texas. The authors stress three causes: some migrant remains may never be found; the bodies of drowned migrants that turn up on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande are not recorded by CBP; and bodies found on private property are not reported to county authorities.

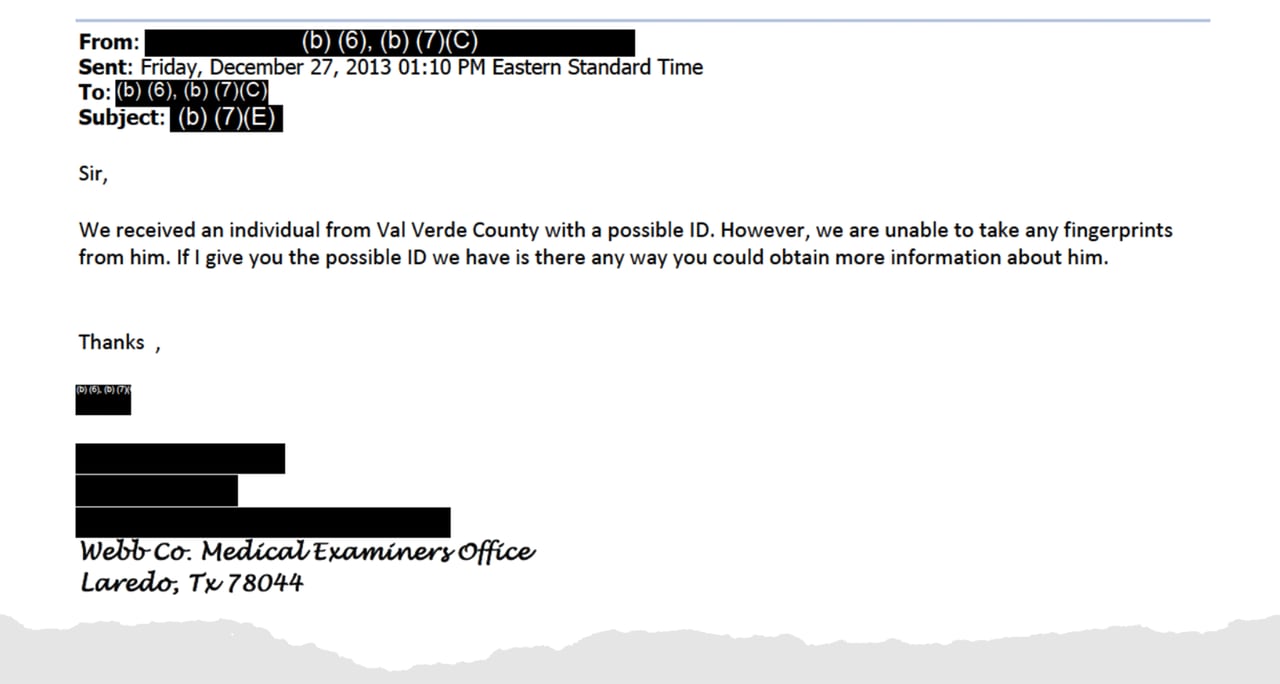

When ranchers do call the authorities, the county sheriff or border patrol picks up the body with a justice of the peace who determine the next steps. Of the 32 border counties, very few have a morgue. Therefore, in many cases, a payment of up to $800 is required to transfer the remains to the nearest morgue. Many times the counties do not have the necessary funds.

E-mail exchanges between investigators in Texas. FOIA request made by Yael Grauer.FOIA request made by Yael Grauer.

In the best case scenario, the judge calls a funeral home that arranges for the remains to be transferred to a morgue for examination and DNA sampling. The samples are then sent to a laboratory, probably the one located at the University of North Texas (UNT), and a case file is opened with NamUs.

In the worst case scenario, the body is taken to a community cemetery and buried as a John or Jane Doe.

Despite the difficulties in recovering and identifying bodies in Texas, initiatives to assist with the process have been established at universities and social organizations such as the Forensic Anthropology Center, led by Kate Spradley at the University of Texas at San Marcos. Spradley’s forensic anthropology laboratory receives migrant bodies from counties that do not have a morgue or lack anthropologists to analyze osseous remains.

E-mail exchanges between investigators in Texas. FOIA request made by Yael Grauer.FOIA request made by Yael Grauer.

In addition, it has a program called Operation Identification, in which the anthropology team travels to community cemeteries in counties where they suspect there may be migrants buried, and perform exhumations.

UNT has the Human Identification Center, one of the largest genetic identification laboratories in the United States. They receive samples from all over Texas and from other states.

Proyecto Frontera

Mayan families who live in the mountains in Guatemala, Buscadoras por la Paz (Searchers for the Peace, a name adopted by mothers and relatives of missing persons who are devoted to finding the remains of their loved ones), social organizations working with those families and government officials all mention the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF).

The non-profit was founded in Argentina in 1986 at the height of the search of the human rights organizations struggling to identify their disappeared loved ones during the dictatorship that ruled the South American country from 1976-83.

With time, the EAAF became a scientific reference in the Americas’ forensic anthropology. Its team supports several countries in the region in their training and field work. After collaborating with the femicide victims in Ciudad de Juárez in 2005, they realized that the identification challenges were due to the fact that most of them were migrants and their families had already claimed they were missing. Sometimes, those claims had been filed in other states in Mexico or other countries in Latin America.

In order to create a regional mechanism of forensic data exchange around missing migrants and unidentified remains, the EAAF launched Proyecto Frontera in 2009. To put it simply, they build bridges of cooperation between the migrant’s homelands and the places where they go missing.

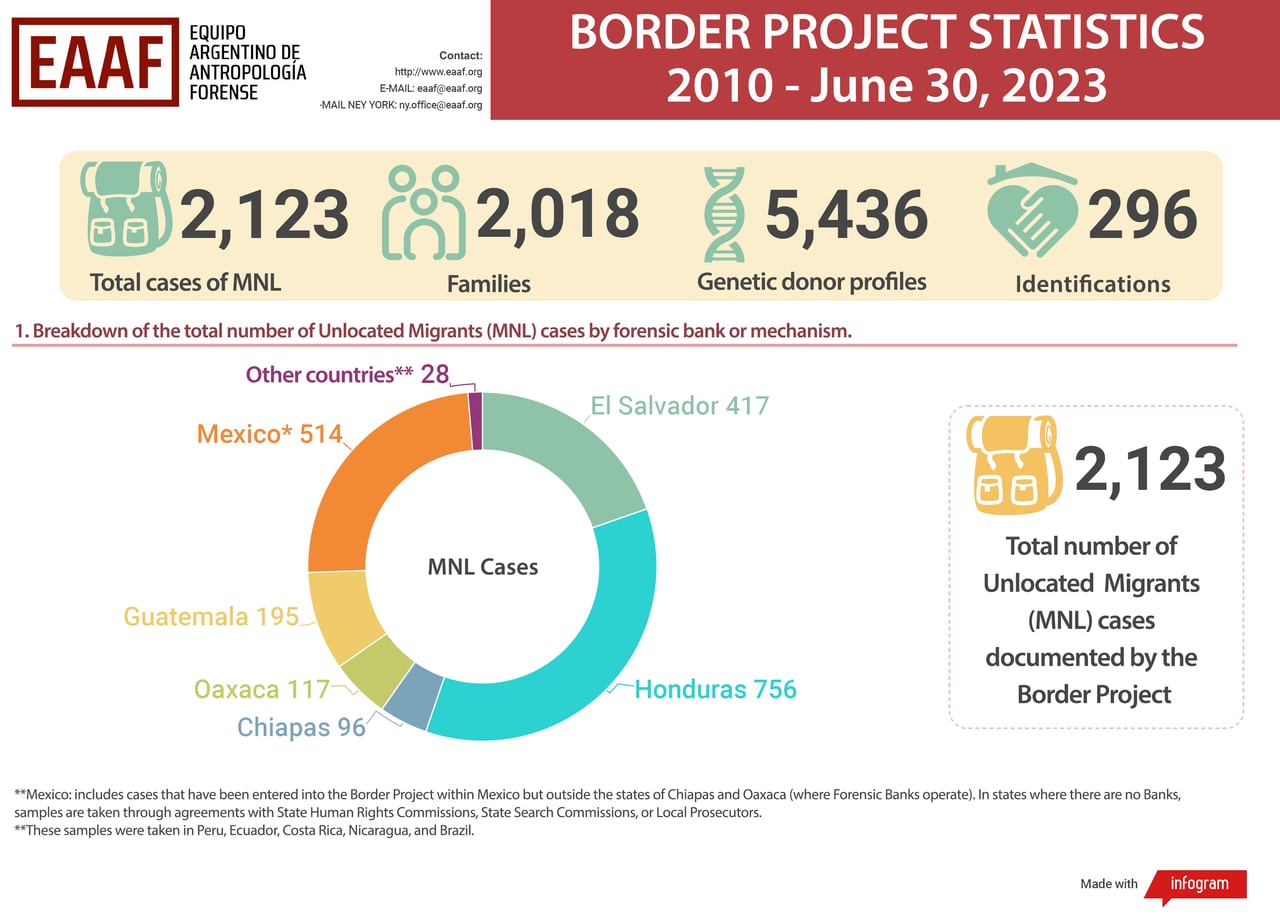

They also boost the creation of databases with forensic information of the missing migrants, using their families’ genetic data. They train forensic experts locally and they make agreements with U.S.-based morgues for data crossing. By March 31, 2023, their register contained 2,059 cases of untraced migrants who were on their way to the U.S.

Image: The Argentine Forensic Anthropology TeamThe Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team

In 2010, the EAAF approached the Pima County forensics office about working together in the collection of genetic data. The office accepted straight away. They found a simple method: since both organizations were working with the same forensics lab in the U.S., they authorized that lab to cross-reference the genetic profiles the EAAF had with the ones Pima had. In that way, none of them would access each other’s databases directly, but they could carry massive cross-referencing. In 13 years, they’ve achieved 100 new identifications.

The EAAF also works with the University of North Texas and Kate Spradley’s lab, which helped them access something they’ve been longing to for a long time: CoDIS.

The FBI database

The Combined DNA Index System (CoDIS) is an United States database that gathers DNA information, and is operated by the FBI at three levels: national, state and local. To use it for the identification of the migrants that died crossing the border would be helpful for the family’s search; they would just need to include their DNA information.

But the FBI rules ban the access of samples taken by non-police organizations. It also requires the full names, their address and other personal information from the family members who give samples. Family members who, in many cases, don’t have an immigration status.

That’s why in 2018 the EAAF and 40 civil society organizations from Central America, Mexico and the United States (with legal assistance of the Berkeley University Law Clinic) requested a hearing with the Inter American Human Rights Commission, IHRC, to discuss these obstacles.

Mercedes Doretti, coordinator with Proyecto Frontera, finished her testimony before the commission by saying: “the United States has the technical abilities and the resources to carry out the genetic comparison at a large scale, which could not just help the families of the missing migrants but also provide with an example of cooperation in global forensics, and for other migrant trails across the world.”

They worked to develop protocols and privacy agreements with US authorities, and created a process for DNA crossmatching.

And, as the University of North Texas’ laboratory has access to CoDIS at a local level, the possibility to use the cases administered by the University and cross them with the EAAF cases was opened.

The Argentine team sends the genetic profiles and a description of the missing person, information about their bonds with the people providing the samples and their informed consentment, among other files, and the UNT analyzes those documents. When everything is greenlit, they upload them to the CoDIS humanitarian database and look for potential matches.

“We started sending cases in February 2023, and we’ve almost sent 100 so far,” said Doretti. Between October 2019 and September 2022, 1,589 migrants died attempting to cross the border, approximately 200 fewer deaths than occurred during Hurricane Katrina. These facts emerged after a FOIA request filed with CBP. The remains of those migrants, once they’re in U.S. soil, can end up in a box, cremated or in a mass grave without their loved ones knowing it.

Ofelia Muñóz Valenzuela lived in Veracruz, Mexico. Her abusive husband beat her and her daughter. She fled from him in 1997, leaving her daughter in the care of her grandmother before heading towards the U.S. She was deported during her first attempt.

The last time she and her daughter spoke on the phone, Ofelia said she’d try again.

It was 2011 when a sheriff’s office in a Texan county found a skull during a cleaning. Someone had given it to a police officer in 1998, and he had kept it in a locker. Itt probably belonged to a migrant who had died in the desert. The skull was filed for identification and, in 2018, it was confirmed that it belonged to Ofelia.

Elena, her daughter, had gone 20 years without knowing what had happened to her mother.

This investigation was produced with the support of the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR) led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).

__

Verónica Liso is an Argentinean product manager for digital native media and a freelance investigative journalist since 2013. She specializes in judicial journalism and data journalism. She has published in Cosecha Roja, Infojus Noticias, Página 12, Revista Anfibia, eldiario.ar, Perycia, among others.

Rosario Marina is a journalist specializing in data and narrative. She studied at the National University of La Plata, in Argentina. She has been covering human rights, gender and LGBTIQ issues, migration and police violence for 10 years for media outlets in Spain, Guatemala, the United States and Argentina.

Gabriela Olga Villegas is a regional digital content editor for Univision Texas and Chicago. She is the winner of a Lone Star EMMY for winter weather coverage in North Texas with the Noticias 23 team. She worked for more than seven years as a journalist for El Norte and Reforma in Monterrey, Mexico, where she began in daily news coverage and also conducted investigative journalism focused on corruption that had a national impact, such as the detour of resources in social programs and the favoritism of politicians with companies to distribute contracts and bids.

Andrea Godínez is a Guatemalan social communicator with a career of seven years dedicated to photojournalism and production of journalistic content, covering issues of migration, poverty and social inequality. She studied Communication Sciences at Universidad Rafael Landívar.