Disease, crime, AI! Is the sky falling or not?

This is an opinion column.

My dad died a decade ago. A thousand years ago.

He’d spent life as a Methodist preacher, and in the weeks before dad died he said the same line over and over to anyone who asked how he was doing.

“Heaven’s my home,” he’d say. “But I ain’t homesick.”

As death drew close he stopped saying that so much. I don’t know if he was homesick, but he knew it was time. He was content, and before long he was gone.

I joked recently that it was a good thing dad died in 2013. Because 2023 would have killed him.

The United Methodist Church he loved split from the inside, especially in Alabama, where disagreements over gay marriage led more than half of all congregations to leave a denomination that for years advertised itself as a place of open hearts, open minds and open doors.

His beloved Birmingham-Southern College is on the rocks, damaged from within and without. Science, which he revered, is under attack. Nature, which he adored, is under threat. Institutions he counted on – higher education, the press, the courts – struggle in a world made uncertain because of its own advancement. Wars rage, and, in politics, lies are preferable to compromise.

Yeah, I’m glad dad didn’t see it. If he woke and saw a world more bent on breaking things than improving them he’d climb right back in that coffin and slam the lid.

Except…

Except we tend to lose ourselves in the moment, in justifiable fears the world is going to hell in a Gucci handbag.

It’s rational to worry about the directions we head, to be concerned for the world we leave our kids. Of course it is. But that’s not all there is.

Because we live in a world that is more literate, more educated, less violent, less discriminatory, more mobile and longer-lived than that of our forebears. We can complain in Alabama that our life expectancy of 75.5 is more comparable to Uruguay than Hawaii, but it’s 10 whole years better than it was in 1950, when 65.9 was all you could expect.

We live in a world where vaccines have become political, but one in which they have almost ended our fears of crippling polio, whooping cough, diphtheria and many more.

Even Alabama, which lags in many health categories, is a state where syphilis is down 89 percent from 1993, where only one case of mumps was reported last year, where hepatitis A and B declined 63 percent from 1996.

Those institutions people love to hate have been pretty good to us.

Despite population growth, overall crime in Alabama for the decade that ended with 2019 was lower than any decade since the ‘70s. Alabama’s murder rate for the most recent decade was about half what it was in the ‘60s, about two thirds what it was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. The rate of burglaries has dropped every decade since the ‘70s.

We have tragic wars. As we always have.

We have crippling fears. As we always did.

We romanticize our past and fight over the future. As we always will.

But we have hope. As we always must.

It makes me think of my dad again, and the words in his obituary that summed up his lifelong philosophy:

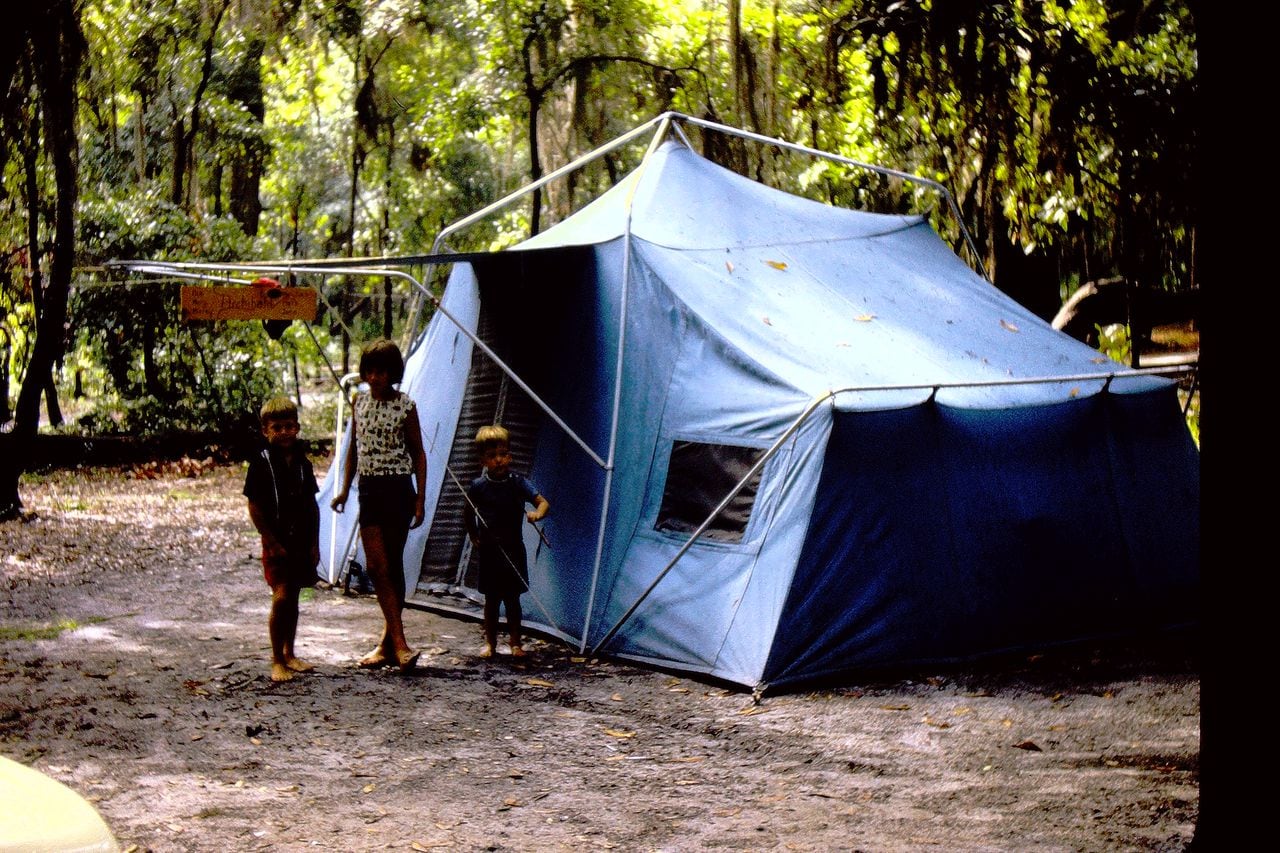

“His advice in life, to his children, his scouts, his campers, his congregation … was much the same: Leave your campsite cleaner than you found it; leave your neighborhood, your community, your city, more joyful that you found it; let the world be better because you were there.”

We may not be able to change the world, but we can damn sure change our part of it.

John Archibald is a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize.