Dems in crowded D2 field hope to sway voters with videos; whose do you like?

This is an opinion column.

With apologies to Rod Stewart, every video tells a story, too.

In the glutted field of 13 Democrats vying to represent Alabama’s sprawling, newly drawn Congressional District 2, several have already launched videos they hope to convey a story that will separate them from the disparate pack.

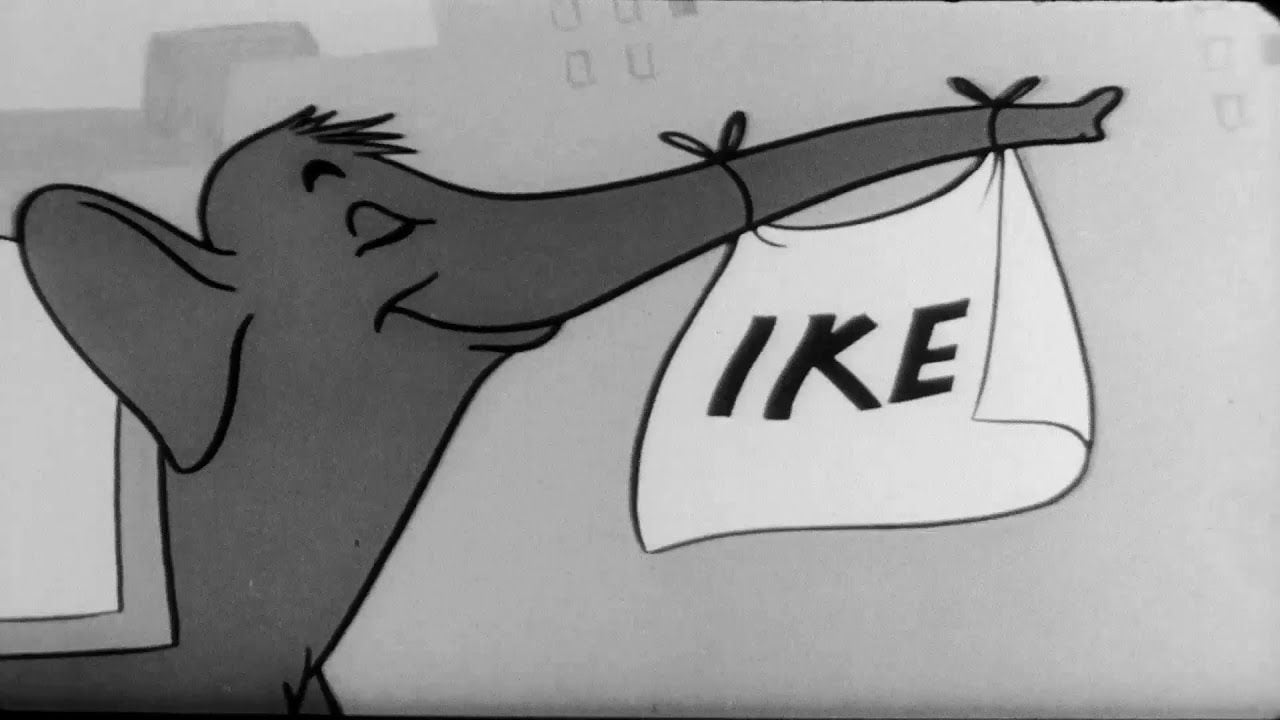

Campaign videos are not new, of course. Campaign commercials go back as far as television (this nerd-nip site archives them back to 1952), and peppered voters with jingles (“You like Ike, I like Ike, everybody likes Ike,” Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1952), jabs (“Agnew for President? …This would be funny if it weren’t so serious,” Hubert H. Humphry, 1968) and jittering claims (“We must either love each other, or we must die…the stakes are too high for you to stay home,” Lyndon B. Johnson, 1964).

Some were persuasive, many were pitiful. In recent election seasons, with right-wingers tooting guns in their ads amid an era of historic mass shootings and deaths, some are both—sadly.

These early videos from District 2 candidates—five thus far—aren’t at all dark. Nor do they attack (at least not yet, or not blatantly). State Sen. Merika Coleman, Rep. Anthony Daniels, Shomari Figures, Rep. Juandalynn Givan, and Rep. Jeremy Grey (their videos are embedded in alphabetical order) all produced warm handshakes designed to, in essence, tell their story.

Tell their journey.

Their roots.

Each addresses what are thus far the two primary—if not sole—storylines in a race where several candidates reside outside district lines (which is allowed by the U.S. Constitution): Where do you live, and who are your people?

Campaigns are still largely won or lost with solid, data-based strategies targeting likely voters, and boots-on-the-ground, face-to-face show-leather canvassing. Yet, Davison says, in an age when we digest as much content on our phones as on television (if not more), videos are “extremely important.”

“In the age of social media,” he says, “it gives you a snapshot of who the candidate is, their platform, and an idea of: Do I actually like this person? That’s important because everybody’s scrolling through their phones looking at the best videos with the best graphics, and the best representation of the voters’ values. If you’re doing a video and you can’t capture what people are thinking, it’s a missed opportunity.

“You get 30 to 60 seconds to do it, but I’m telling you, if your video is dull in the first five seconds, they’re scrolling on to the next one.”

Davison wouldn’t critique the five videos, which range from just over a minute to nearly three minutes and could’ve cost between $5,000-$15,000 to produce. “I’ve seen some candidates with television crews, some with iPhones,” he said.

“We have some really good, really interesting videos, to say the least,” Davison said. “A couple help you understand the candidate with a lot of backstory, a snapshot of their journey. Some came from a community where they were never represented, went off, then came back. Some who’ve always been a fighter in the community, fought in different offices where they could make change for the entire state. Then some stand on a family legacy, they want to hold the mantle and fight for the communities they came from. You’ve got a variation of all of that.”

Over the next three months—the primary is March 5—the videos are likely to be sliced, diced, and re-edited myriad times. Some campaigns might even produce new videos, targeted, perhaps, at specific communities (the district traverses the entire state) or opponents. Though candidates must be mindful their productions don’t douse their “like” factor, especially once they begin canvassing.

“Let’s say, I shake your cousin’s hand and they come to you and say, ‘Man, I met that guy, Ollie, he’s running for office.’ If you’ve seen that video. I just got two for one because your cousin is the validator. Your connectivity from watching the video is gonna make you say,’ He must be a good person.’ Or even a bad person. Your cousin could say, ‘Hey, I met that guy, he was a total jack—.’ You, having seen the video, make it a double loss. It just depends on the experiences.”

“We live in a big state but it’s still a small community, a look, feel, touch community,” says Davison. “You can do that can efficiently with technology—videos, texts, direct mail, and robo calls. That makes for a fuller campaign.

“But the most important factor in a campaign is connectivity to voters. Especially in Alabama, if I can look in your eye, shake your hand, and tell you the reason why you should vote for me, that always goes further than a text message, or even a video. It gives me a better idea if you’re somebody who connects with my values. It’s the personal touch. Alabama has always been a state where if you are personable to a voter, then odds are they will go to the polls and vote for you.”

Note: As other candidates release videos they will be added here.

I’m a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and a member of the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame. My column appears on AL.com, as well as the Lede. Check out my podcast series “Panther: Blueprint for Black Power,” which I co-host with Eunice Elliott. Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, The Barbershop, here. Reach me at [email protected], follow me at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj