Dawoud Beyâs âThe Birmingham Projectâ is returning to the Birmingham Museum of Art

Ten years after its debut at the Birmingham Museum of Art, “Dawoud Bey: The Birmingham Project” will make a return.

The series of black and white photographs symbolically commemorates the four young girls and two boys who were killed on September 15, 1963 in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley were killed when a bomb set by white supremacists detonated inside of the church that morning. Later in the day, two boys–Virgil Ware and James Johnny Robinson– were killed during the resulting violence.

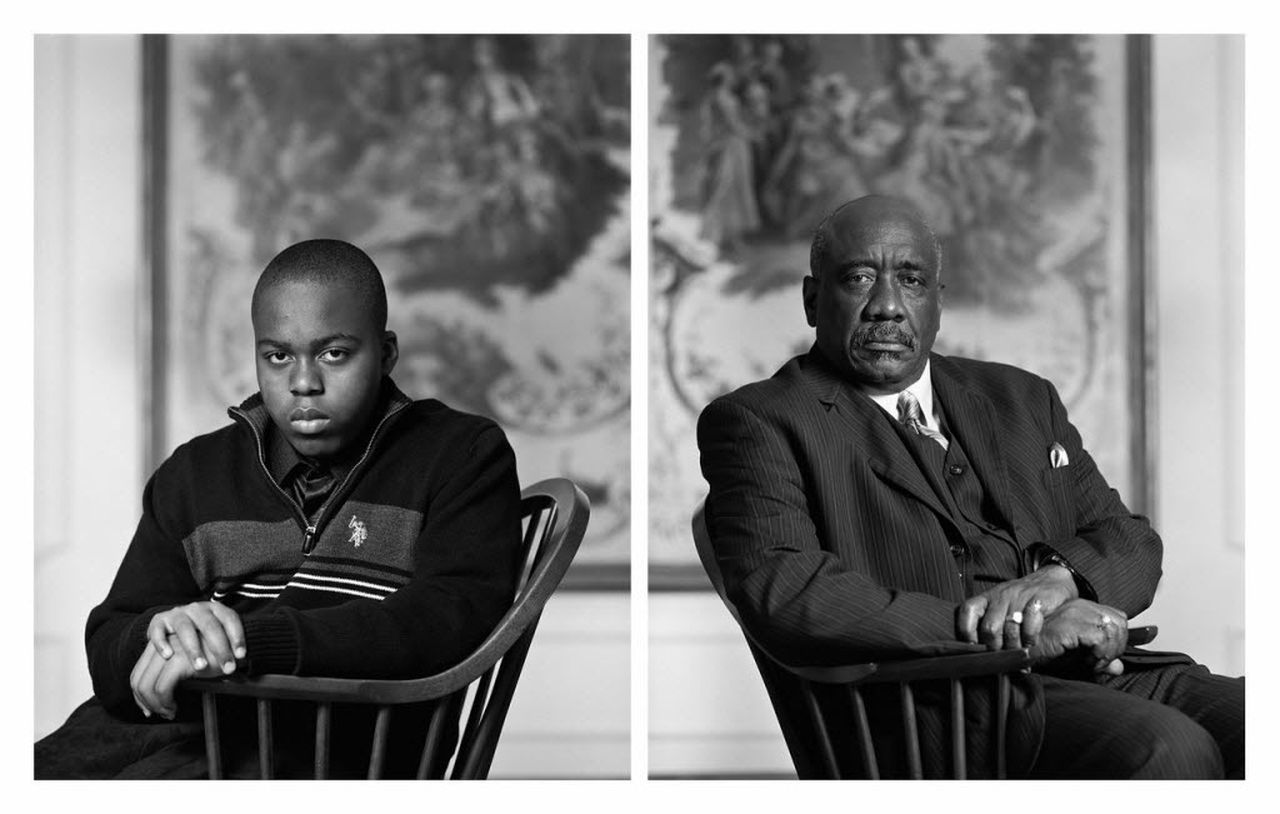

The portraits in “The Birmingham Project” are combined into diptychs. In each diptych, Bey paired children who were the same age as the victims at the time of their deaths with adults who were fifty years older, the same ages Collins, Robertson, Wesley, McNair, Robinson, and Ware would have been if they were still alive.

“The Birmingham Project” (Courtesy, the Birmingham Museum of Art)

The exhibition opens to the public on Sep. 14, as part of the city of Birmingham’s year-long series of programs commemorating the 60th anniversary of the 1963 civil rights movement.

“Renowned for his remarkable ability to capture the essence and humanity of his subjects, Dawoud Bey presents a series of striking portraits that pay tribute to the six African American children who lost their lives that fateful day,” the museum said in a press release about the exhibition.

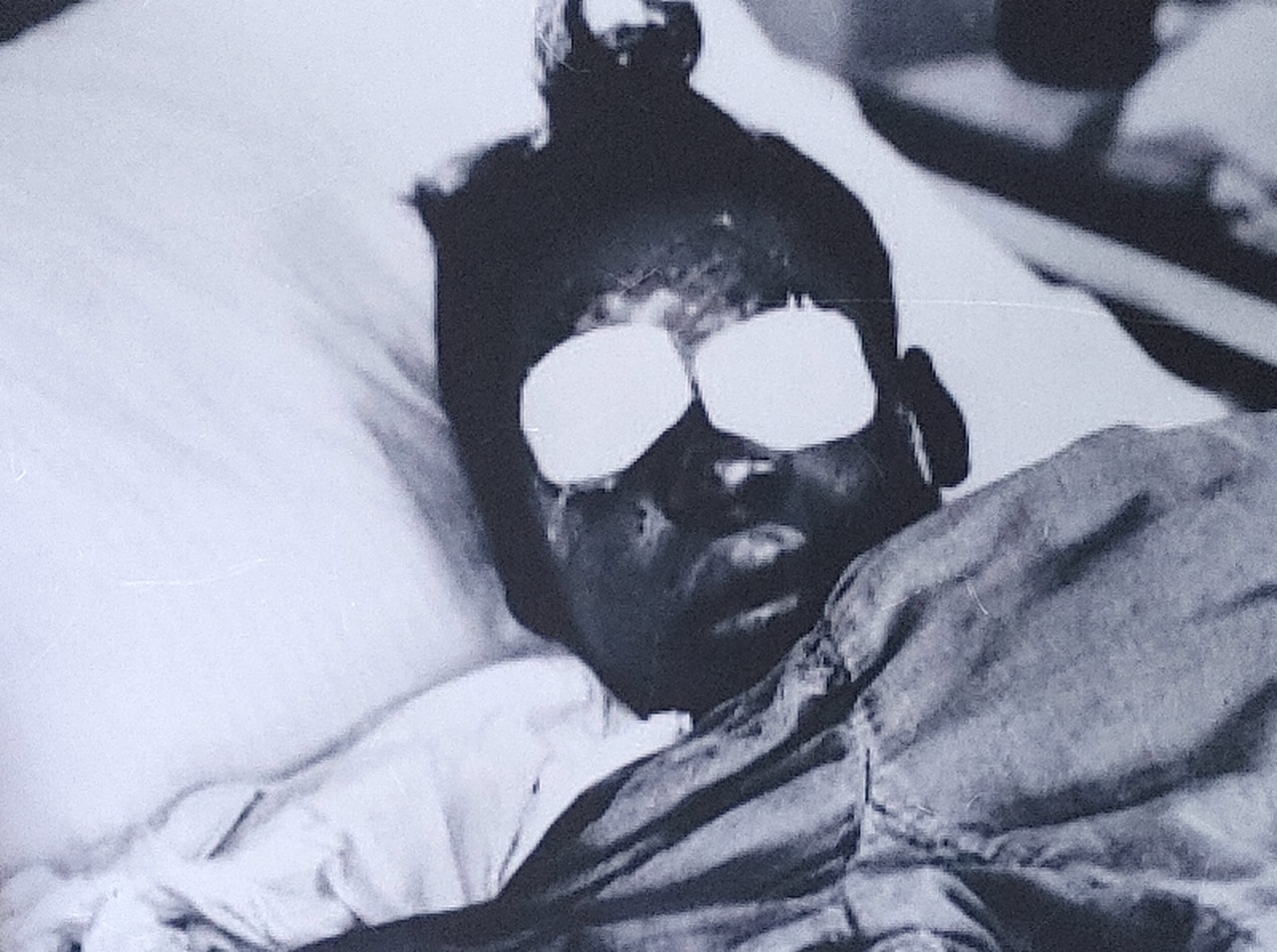

Bey was 11 years old when he first saw a photograph of Sarah Collins lying in a hospital bed with bandages covering both of her eyes. He saw the picture in a book his parents brought home – Lorraine Hansberry’s “The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality.”

Collins, the sister of Addie Mae, was severely injured during the blast and would eventually lose one eye. The photograph, taken by Frank Dandridge, first ran in LIFE magazine’s Sept. 27, 1963 issue, becoming one of the signature photographs to depict the horrors of the civil rights movement in Birmingham.

“That picture resonated with me in a very horrific and profound way,” Bey told The Birmingham News in 2012.

Sarah Collins, “The Fifth Little Girl” in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, in hospital bed.

READ MORE:

‘God had to do a work in me’: Sarah Collins Rudolph on reclaiming her story

‘The 5th Little Girl’: Book on church bombing survivor Sarah Collins Rudolph complete

Birmingham foot soldiers recount experiences before 60th anniversary of church bombing

For years, Bey had an idea for creating a project dedicated to Birmingham. Once he visited the city, the idea became more tangible. However, he wanted to work with the community to develop the concept for an exhibition. So he met with creative leaders, educators, and historians in the city, including curators and the board of trustees at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Odessa Woolfolk and the team at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, and the pastor and congregation of 16th Street Baptist Church.

He had conversations with the BMA’s Sankofa Society– the museum’s support group for African-American Art. After years of discussion, Bey decided to shoot the portraits at two locations: Bethel Baptist Church– the home church of minister and civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth— and the Birmingham Museum of Art, which was segregated in 1963. Then he took up residence in a temporary studio at the museum where he shot and selected the photographs. The result– black and white photographs of men, women, and children looking calmly and intentionally into the camera, as if they were making direct contact with the viewer.

Photographer Dawoud Bey checks proofs in 2012 at a temporary studio at the Birmingham Museum of Art. The Chicago-based artist spent a year photographing boys and girls, men and women for the project commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. (AL.COM/TAMIKA MOORE)

“Here is someone who has worked with institutions for years, drawn the public into his work,” Ron Platt, the museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art, said of the exhibit in 2013.

“It operates on different levels. It represents a cross-section of our black community, and it’s a memorial without being too heavy. It leaves a lot of room for viewers to explore and find things on their own.”

“The Birmingham Project” has been on view in a number of institutions around the county since its debut, including the Whitney Biennial and the George Eastman House.

In 2017, a print of the diptych featuring Mary Parker and Kayla Coleman returned to the Birmingham Museum of Art for “Third Space” a two-year exhibition focused on shifting conversations about contemporary art.

Kayla Coleman stands in front of her portrait with Mary Parker from “The Birmingham Project” during the “Third Space” exhibition opening party on January 27, 2017. Dawoud Bey took the photographs in 2012. (Shauna Stuart| AL.com)

The National Gallery of Art hosted the series from 2018 to 2019, coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. During the exhibition in Washington, D.C., Bey recounted the experience of seeing Sarah Collins’ photograph for the first time.

“This photograph seared itself, seared its way into my psyche. I don’t know if intuited at that moment that I was pretty much the same age as the girl I was looking at. The visceral response may have well been related to that, but I never forgot that photograph, and I very often describe my life as my life before and my life after this photograph,” said Bey, Culture Type reported. “It was that dramatic and traumatic [of] an experience, seeing this photograph.”

Earlier this year, the Birmingham Museum of Art announced it had purchased 10 photographs to complete the set of large-scale diptychs from “The Birmingham Project.”

“The Birmingham Project,” Dawoud Bey, 2012 (Courtesy, the Birmingham Museum of Art)

“Bey forces the audience to consider the enormous loss of potential that each of these children represented,” the museum said in the announcement. “The complete set of 16 photographs and a video bolsters the Museum’s collection of art focused on the Civil Rights era and adds to a burgeoning collection of American photography.”

Graham C. Boettcher, the R. Hugh Daniel Director of the Birmingham Museum of Art, describes Bey’s work as a “contemporary perspective on a historic tragedy.”

“The Birmingham Project explores the complexities of race, identity, and remembrance in a way that encourages reflection and dialogue,” said Boettcher in a description of the exhibition.

The museum is giving the public an opportunity to engage in a conversation about the exhibition this week as part of commemoration week, a series of events commemorating the 60th anniversary of 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church. On Wednesday, Sept. 13 at 6:00 p.m., Bey will serve as the speaker for the BMA’s annual Chenoweth lecture with scholar and Harvard Radcliffe Institute professor Dr. Imani Perry. Together, Bey and Perry will explore the role of art and photography in addressing race, culture, and history. (Registration to attend the lecture inside of the museum’s auditorium has reached capacity, but a simulcast of the event will be available in the museum’s upstairs cafe for walk-in attendees).

Imani Perry, a Birmingham native, is a scholar of law, literature, history, and cultural studies, as well as a creative nonfiction author. In 2022, she won the National Book Award for Nonfiction for “South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation.”

READ MORE: Alabama native Imani Perry holds one of the nation’s top literary honors

Perry examines the impact of 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in “South to America,” including the effects the murders had on Birmingham’s legacy. In the most recent edition of “Unsettled Territory,” the weekly newsletter she pens for The Atlantic, Perry nodded to the upcoming conversation with Bey, as well as the 60th anniversary of the bombing.

“This was neither the first nor the last time Black children were killed in the South as a message that white supremacy would be maintained at all costs. And it was neither the first nor the last time that the response from Black southerners was more complex than simply nonviolent resistance,” wrote Perry. “In fact, even the term civil-rights movement is in a sense too narrow to describe what was happening in Birmingham and other communities. This was a freedom-movement era, in which some Black southerners focused on civil and legal rights, others focused on economic.”

READ MORE:

BMA Director reckons with Art Museum’s ugly past

16th Street Baptist celebrates 150-year ‘legacy of resilience’ in Birmingham