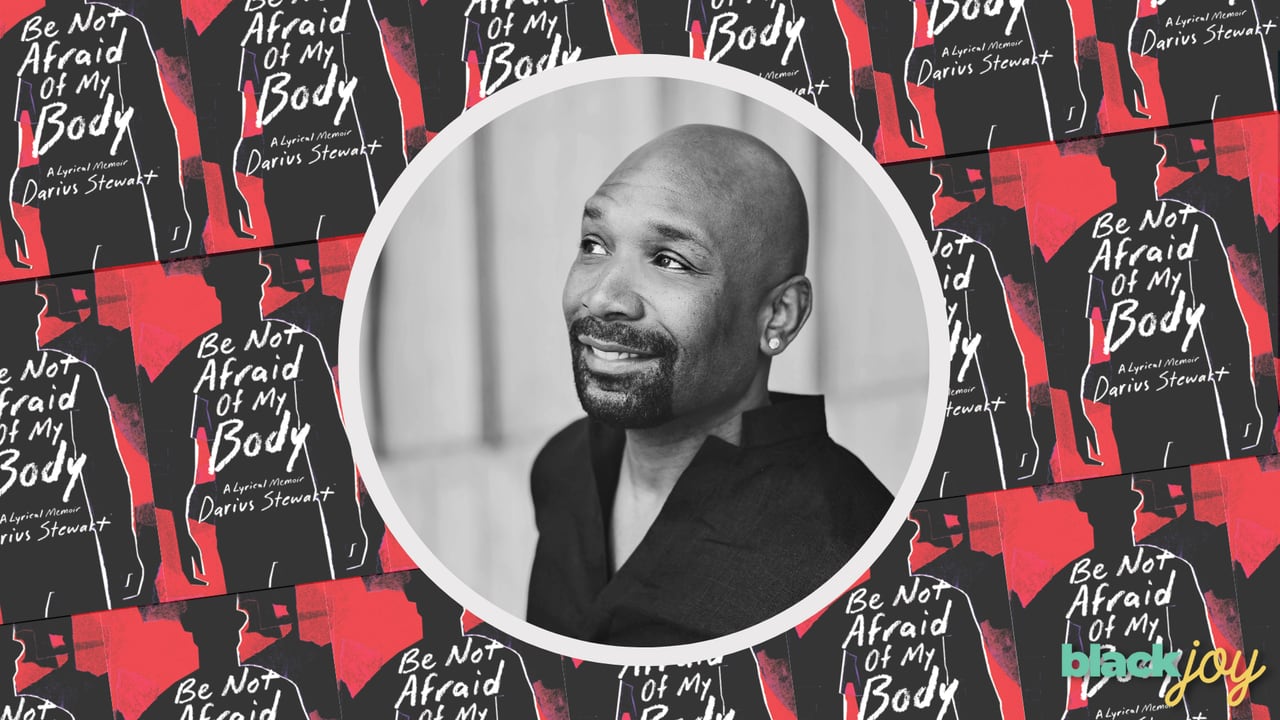

Darius Stewart on his search for self and writing his memoir âBe Not Afraid of My Bodyâ

Self-discovery is a series of life-altering experiences and in the end you’re often able to give a name to what you’ve been through. In his memoir “Be Not Afraid of My Body” author and poet, Darius Stewart, takes us through his journey as a Black gay man trying to find his place in the world. Through lyrical prose that floats between insightful streams of consciousness and beautifully vivid imagery, this book tells a story of love, grief and survival.

Black Joy chatted with Stewart about how his memoir came together on the page, what he learned about himself while writing and the readers he hopes this book will reach.

I read an interview you did where you talked about the importance of saving those bits and pieces of things you write to essentially create a larger project. Can you share your journey of finding the thread that connected the individual pieces that came together to shape this book?

“Be Not Afraid of My Body” was easier to find those threads because I already knew what I was basically gonna be writing about. I knew it was gonna be about my health. I knew it was gonna be about my addiction. And it was gonna be about my family dynamics, coming out and all of that. And those were some of the larger pieces or essays in the memoir. But there were some connective tissue pieces that I had to think about like how to bridge one piece to the next in a way that let the reader kind of mellow out a bit because some of the material can be overwhelming.

I should back up and say, when I went into this project, I knew that I didn’t just want to reveal a bunch of things. I was really searching for myself in a way. Who is Darius Stewart, in the sense that, I become all of these things—an addict, a person living with HIV and heart failure, all of those things. What’s the bottom sum of all of that? And so some of those connecting moments, those threads, came out of that searching.

As you were writing and revisiting these different eras of your life, did you have any revelations about experiences you’ve spent your entire life feeling one way about up until putting it into context with the larger story of your life?

Yeah, I think the wonderful thing about writing the book is that I feel like I did achieve what I ultimately set out to do, which was to kind of understand why I am the way that I am, why I’m this person who did all those things. And it basically boiled down to, I have this sense of perfectionism that is kind of dovetailing with this need to be liked and affirmed by other people and the reason for that is because of my father. My parents had me young. They were both teenagers when they had me. and then my father ended up going into the military. So, not only was he young and inexperienced as a father, but he had this kind of drill sergeant mentality in terms of how he raised us. I have a brother and sister and I’m the oldest. So he made sure that I was always doing things perfectly and because of that I needed to do things perfectly and then seek his approval for that.

And so, as I grew older, for me, it became like this pathology. . .like I don’t drive to this day because I failed the driving test the first time that I took it. And that’s the thing I would do, if I didn’t succeed at it, then I would just chuck it and just move on and it’s not really the healthiest thing to do. And so I feel like the stuff that I’m working on now is kind of extending that, because I think I mentioned it in one piece “Dearest Darky” when I write about all the horrible things that I’ve done to get ahead in the restaurant business and what I endured in terms of the racism and all of that, all of it boiled down to the fact that I just needed approval and to be liked. But by the time I had written that and come to that realization I didn’t feel like doing more of that labor for this book. I can save it for another project.

There were a lot of heavy moments throughout this memoir, what joy from this time period lay just beyond the frame of the story your book tells?

Certainly, there are moments with my mother. Of course, it can’t just be pure joy. It always has to be like finding the silver lining in a sense. Ending with this image of the mother as the caretaker of the child and making everything better in the piece, “You Don’t Have to Like It.” It ends with them dancing together and then [the child] does something and at the end of the piece, he ends up just watching his mother dancing by herself and humming and he’s content with that.

So, there were certainly moments of joy that I found with her, but also there were moments of joy in the tone that certain pieces would take like some of the more what I would consider irreverent forms, like “Imaginary friend” and “The Drunken Story.” I had fun writing those pieces even though they are about some disturbing aspects of my life, particularly as it pertains to addiction. But I liked being able to invoke this kind of joy in the piece through scene but also invoke joy formally with how the piece is written.

I’m glad you brought up the scene with you and your mom. I think that was the scene where you broke the TV by accident. But I thought it was just such a tender moment. But there were also definitely points that felt, even in the heaviness, joyful, like during the cookout scene when your friend overdoses. It was two things happening at once. I can hold that serious part but also see the community aspect.

Absolutely. And yeah, that’s interesting because of the kind of inherently cultural gestures that occur. When I say inherently cultural gestures, I mean, Black people getting together for a cookout and there’s this subtext of whiteness. . . what happens when you have this joyful moment that is interrupted by this overdose and it’s a white person at that [and] what is it saying, not just in that moment of the text, but in a larger cultural understanding of what Blackness is as it exists within this framework of white supremacy.

When you think about future readers, who do you hope this book will reach and why?

I’ve anticipated this question or some variants of it. And I thought I knew, but I’m not sure I do. In the general sense, Black gay men are certainly a target demographic, especially Black gay men of a certain age. And that gets tricky too because you would think perhaps that my book will want to be geared towards a younger demographic. And that is true. Because, on the one hand, I want to be able to provide something for a generation, the way that Essex Hemphill provided for me, and Baldwin provided for Essex Hemphill, that kind of thing.

There’s also my generation, but also generations older than me who didn’t have the opportunity to be who they really wanted to be . . . so, my writing, when I think about it in that way, I’m anticipating that I’m speaking to multiple generations who all pretty much converge on the same need but just from separate kinds of experiences. On the one hand, the younger generation, this is something that they can readily have at their disposal. Whereas, an older generation might be able to have a kind of engagement with the text that could still teach them something, but also make them feel a certain kind of pride.